|

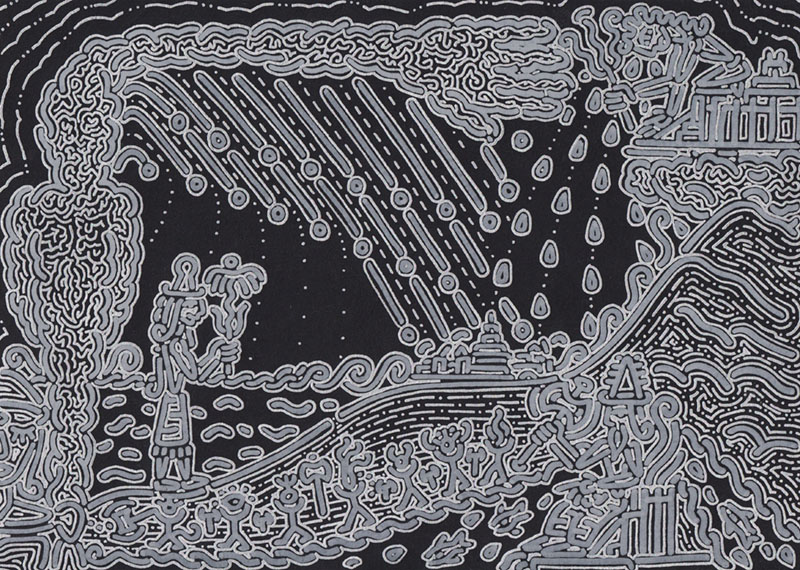

In the years 2010-12, I engaged in lengthy researches into the Eleusinian Mysteries, seeking to penetrate the veil that had descended over those secret rites with a conviction that what had been anciently concealed would have great value for modern humanity. In brief, I found that the experience of the celebrants at Eleusis involved a radical transformation of perception through the inherence of shapeshifting deities, the consumption of a visionary sacrament and a world-healing ritual of such efficacy that the rites culminated in a visio beatifica granted by the visit of Persephone in her guise as Thea, Everliving Goddess as Visionary Event. From this research was liberated a series of artworks entitled 'Eleusis' and an accompanying book of art and essays which is currently out of print. Since that time, my thoughts on Eleusis have developed further, and this essay draws parallels and contrasts with other mythical images in which the male acts as magical helper in female-oriented mythforms.

1 Comment

After a short hiatus, we continue with my serialisation of 'On Vision and Being Human', in which we review a broadly-painted image of the ubiquitous human experience of hidden realms and visionary worlds held to exist beyond mundane reality. Upcoming chapters from 'On Vision and Being Human' will turn the path onto challenging insights from quantum mechanics and neurology which, although not particularly archaic in their outlook, will eventually open us into a powerful new image of human visionary experience. In addition, future serialisations will be interspersed with stand-alone essays of the type with which this blog was begun: coming in the next few months, a look at mythical images of emergence, the Bird Man of Lascaux and the complex beliefs behind Wandjina rock art figures in Australia From the foregoing [previous chapters of this treatise are visible here and here] it is easy to see that a reification of visionary experience might result in a literal understanding of sacred worlds beyond our mundane reality, and it appears that for as long as humans have been recording their visions as art, this World-Beyond-Worlds or ultimate reality has been central to our perceptual and ritual lives, informing profoundly not only the elementary ideas of human experience but also the vast majority of particular cultural forms. Campbell, following Bastien, outlines several of these elementary experiences that he considers to be, in his words, conterminous with the human species, including ideas of:

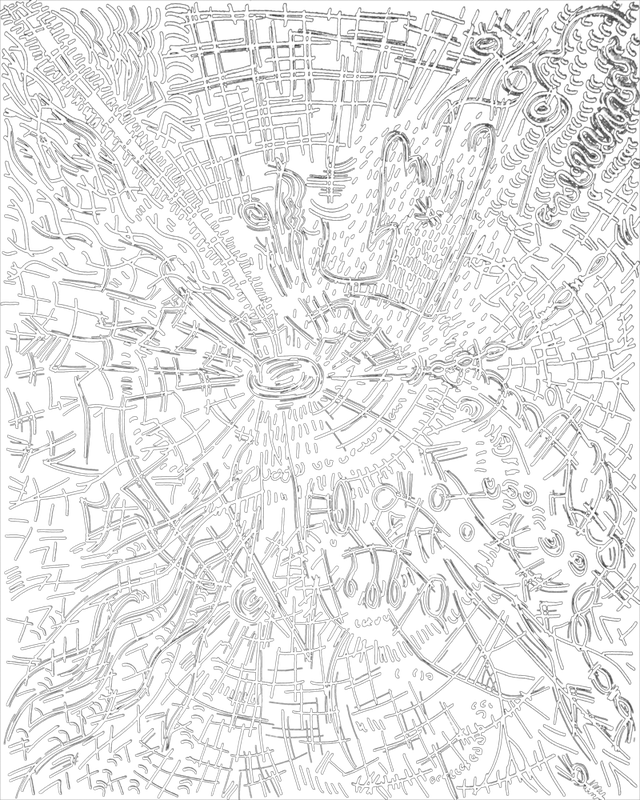

“...survival after death... of the sacred area (sanctuary)... of the efficacy of ritual, of ceremonial decorations, sacrifice and of magic... of supernal agencies...of a transcendent immanent power (mana, wakonda, śakti, etc)... [and] of a relationship between dream and the mythological realm...” Continuing the serialisation of my lengthy essay 'On Vision and Being Human', I present here the first three sections of the essay, which highlights some of the general nature of visionary experiences, and the problems and ambiguities they raise for the modern 21st century mind. Enjoy! 1. On Vision as Sacred Other The question has often been asked: What is Visionary Art? On the surface, the answer would seem to be an easy one: Visionary Art is simply what it says, the art of visions, by which is meant the beholding of mythical worlds and realities beyond the mundane daylight world, of dreams, hallucinations, sacred journeys, inwardly-focussed and meditative experiences, flights of fancy and imaginal and ancestral flights. Complexity emerges, however, when we come to the realisation that each human, artist or not, will hold wholly different perceptions of what these words (or indeed, worlds) mean. We quickly come to further questions: what constitutes a dream, how does a journey become sacred, what do we mean by a world beyond this one, and how does the experience of an imaginal flight become 'visionary'?

In one of my first posts on this blog, I mentioned that one of my writing projects, entitled 'On Vision', would eventually be featured here on 'Archaic Visions'. In the ensuing period, the remit of this writing project has rather expanded, and thus is now called 'On Vision and Being Human' to reflect the wider purview - Darwinist, neurological, cognitive - that I am taking in my quest to come to a new understanding of the nature of visionary experience. As I write, this essay stands at some 45,000 words with a few more sections still to write, and as such, the serialisation here will likely last a long time! Eventually, an illustrated book is planned... For now, however, here is the introduction to the thesis, which I hope will whet your appetite for further reading!

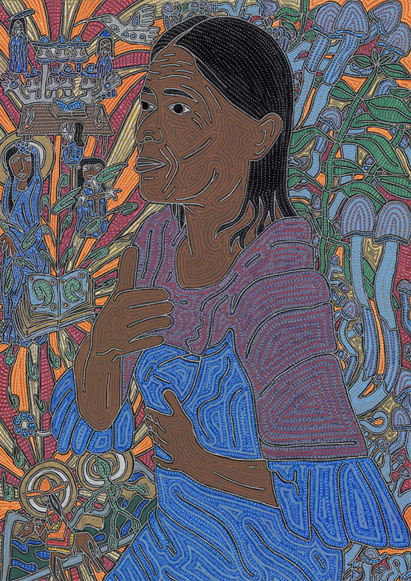

As an artist whose work deals with vision and the experience of myth, the nature of these perennial themes in human culture is of principal importance to me, as is the nature of the art that I do: Visionary Art, a complex and multi-faceted artform. At heart, for me, it is the inner and outer quest to uncover ancient and future sacred images that reveal the deepest wordless essences of what it means to be alive in this cosmos as a human being. The visionary image is transpersonal, and transcultural, unhinged from the personal and from local time, place or culture into realms of myth, of sacred journeys, of dreams and imaginal flights of fancy, shamanic and entheogenic visions, and of half-forgotten sacred vistas shimmering within the Underworlds of our Human Souls. And for all of this to be rendered using techniques that speak of craft, lineage and ancestral lifeways. Some ten years ago, my path as an artist and vision-seeker took a profoundly interesting turn when I began to work with the Mazatec entheogenic plant salvia divinorum, known in Mazatec as xca maria pastora 'the leaves of Mary the Shepherdess'. In seeking to more deeply contact the salvic world disclosed by the visions I was experiencing, I began to become curious about the Mazatec people and their language, and while doing so, discovered that when anthropologists speak about indigenous Mazatec shamanism, all is not quite as it seems. The translation of many Mazatec concepts into English in some of the academic literature seems at least partly ideologically-motivated, and involves a considerable loss of the indigenous worldview, even when other, better English words are available for a given translation. This tour through various Mesoamerican 'shamanic' words seeks to counter that loss, which has passed into the wider visionary culture. The English word 'wise' is a curious term, often synonymous with 'learned' and stative in intent: a wise person is not wise through action, but through having known, the knowledge now functioning as a kind of attribute of the person so described. Cognate with Dutch wijs 'wise' and German wissen 'to know (a fact or situation)', it has its ultimate origin in Proto-Indo-European *weyd- 'see, know', and thus its grounding in this notion of 'having seen, having known' is rather ancient.

Japanese however has no such concept in its lexicon: there are words which are somewhat similar, such as kashikoi 'clever, smart, wise, intelligent', umai 'skillful, clever, expert' and in Classical Japanese of the Heian Period, satoshiki 'clever, perceptive', but these words do not relate to knowing or having seen. Rather they relate lexically to, respectively, 'having grace or humility', 'being generally good or excellent' and 'having realised in a meditative manner' (compare satori, the Japanese translation for 'enlightenment'). Japanese is here sufficiently different from the Indo-European cultural sphere for an appreciation of this difference to be evident. I have suffered – if that is the right word – from migraines since I was a child, and I am lucky – again, if that is the right word – enough to be one of the twenty percent of migraineurs who experience both the visual aura that precedes the migraine as well as the visionary aspects during. Some of my most powerful childhood memories are of sudden dysphoria and immanent sensations of fractured consciousness which are the hallmarks of visionary experience engendered by migraines, and in a sense, I view them now as part of a natural feature of my neurology. This essay takes in a personal and prehistoric view of this important but challenging aspect of my life.

In his Manifesto of Visionary Art, artist and author Laurence Caruana elucidates a near-exhaustive list of the sources and inspirations from which Visionary Art can spring. It is worth quoting: “...the sources of Visionary Experience are many and varied: dreams, lucid dreams, nightmares, hypnogogic images, waking dreams, trance states... hypnotic states, illness, near-death experiences, shamanic vision-quests, meditation... madness... day-dreaming, fantasy, the imagination, inspiration, visitation, revelation, spontaneous visions, psychedelics, reading and... the metanoic experiences brought on by Visionary Art itself.” Palaeolithic Cave Art in Europe is celebrated as a profound expression of deft visionary and naturalistic skill. Once thought to have emerged fully-formed some 28,000 years ago, modern dating techniques and new discoveries are revealing the developmental processes of these artforms from simple dot and line compositions to the more skilfully-rendered friezes at Chauvet, Altamira, Lascaux and others, while at the same time showing that the majority of the art was created in three discrete periods, the early-to-mid Aurignacian (33-28 kYa B.P.), the mid-to-late Gravettian and early Solutrean (24-21 kYa B.P.) and the Magdalenian (18-12 kYa B.P.) with minimal surviving cave art activity between these times. The varied but simplistic art seen in El Castillo cave, Cantabria, Spain, generally belongs to the first two of these periods, but a recent uranium-series dating on one petroglyph dated it to almost 41,000 years, making it the oldest known cave art in Europe.

The Cave of El Castillo is one of several caves containing Palaeolithic art in the municipality of Puente Viesgo in Cantabria, Spain, situated some 20km southeast of the more famous cave at Altamira. Discovered in 1903 by Hermilio Alcalde de Río, the cave contains several chambers in which friezes of paintings are located, and there is evidence to suggest the cave was in intermittent usage from the Auriginacian until as late as the Bronze Age, and that during the Magdalenian may have formed, along with Altamira and other nearby caves, the core territory of a single human group. Indeed, there are several smaller Palaeolithic painted caves within the same mountain as El Castillo, and the area may have formed a key pilgrimage or sacred site for this group. The figure of Europa, and her abduction by Zeus, is considered by many to be the founding myth of Europe – indeed the Phoenician queen lent her name to the continent. A careful teasing apart of the strands of the myth, however, reveal a Pre-Greek deity whose form may be reflected in Minoan iconography: the 'Goddess from the Sea' often seen in images of the Epiphany and other religious contexts. This essay is excerpted and expanded from two sources: my treatise The Minoan Epiphany: A Bronze Age Visionary Culture, an ongoing work-in-progress, and Europa Untouched, a set of research notes for my 'Minoan Honey' series.

Classical Greek mythical traditions are a fascinating fusion of elements springing from both Proto-Greek and Indo-European, as well as Mesopotamian and Anatolian cultures. But one of the strongest currents running through the various traditions originates from the Pre-Greek aboriginal inhabitants of the Aegean, of whom the Minoans were probably the most well-known. A vast array of mythforms and deity names have a profound Pre-Greek flavour, and none more so than the story of Europa. The world's myth systems are replete with giants whose rebellious actions help to shape the world, but the strange Hittite-Hurrian 'Song of Ullikummi' seems to move beyond such archetypal and primordial events to describe real-world phenomena. This pseudo-historicity only becomes clear once we perceive the technical languages enfolded within myth, disclosing a genuinely archaic method of interpreting of the world and its natural processes.

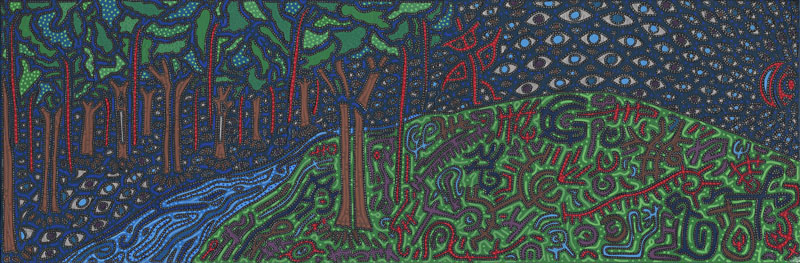

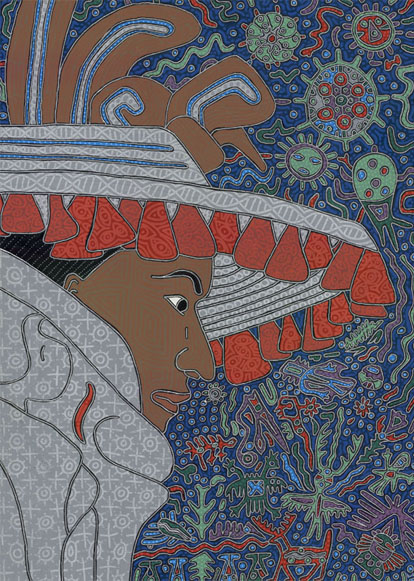

The 14th-century BC Song of Ullikummi is a well-preserved text found among the 30,000 clay tablets in the Cuneiform Royal Archive at Hattusa, the sometime capital of the Hittite Empire, near the modern town of Boğazköy, Çorum Province, Turkey. Detailing a battle between the gods which is occasionally reminiscent of later Greek texts such as Hesiod's Theogony and the myth of Typhon, Ullikummi recounts a somewhat surreal attempt by Kumarbi to overthrow the Storm God Teshub and destroy the city of Kummiya. Rather than being a Hittite story, however, its cast of characters reveals it to be a Hurrian myth from northern Syria, and this tale is one of a large corpus of mythology recorded in the Hittite language that discloses an extensive cultural exchange between the two civilisations. Ramón Medina Silva was a mara'akáme of the Huichol people who also recorded his visions in yarn paintings: indeed, arguably he was the inventor of the visionary yarn painting genre. It was while gazing deeply into a book featuring his artworks and myth narratives one winter evening whilst living in Japan in 1997, that I made the momentous decision to become an artist. I therefore have a profound gratitude for Ramón, his life and his work: his style and vision inspires me to this day. It seems appropriate, then, at the outset of this Archaic Visions venture to express that gratitude in a short essay through which, I hope, Ramón Medina Silva's amazing legacy can become more widely known.

Huichol yarn paintings are justly famous in the world of anthropology and visionary art, expressing as they do the shamanic realities of peyote visions, and the sacred pilgrimages and myth cycles of the Huichol people. There are several notable modern yarn painters, the most celebrated perhaps being José Benítez Sánchez, an initiated shaman whose shimmering and detailed images have been exhibited in America and Europe and whose work is sometimes considered representative of the artform in its full expression of the sacred complexes underlying the peyote vision and the Huichol perceptual cosmos. However, Ramón Medina Silva lived a generation before this widening celebration of Huichol art had come to pass, and he along with his wife Guadalupe de la Cruz Ríos (known as Lupe) were key innovators of Huichol folk arts into the narrative and visionary artforms well-known today. |

ARCHAIC VISIONS

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed