These words of Wunambal elder David Mowaljarlai, in commenting upon a rock painting of Gunduran, a Rain Dreaming spirit, capture in microcosm the essence of the wandjina creator beings as understood by his people, the Wunambal of Donkey Creek in the Kimberley Range. These beings occupy a central place in the mythologies and teachings of the region, and are held responsible for the creation of many of the important landscape features in the Wunambal cosmos. Indeed, many Dreamings are told of these spirits, but the Dreaming in Aboriginal conception should not be thought of as mere liturgy or narrative, but rather as a unified nexus of story, landscape, ritual, ownership, genealogical history and magical creative action of the spirits about whom the Dreamings are told.

“[Wojin] raged when he heard how the two boys had teased and hurt Dumby, plucked his feathers, flicked the naked little bird with speargrass and had then thrown him into the air: ‘Now see how you can fly!’. When Dumby told the wandjina of his misfortune, Wojin brought on an enormous flood that killed all the people in the area – except the two mischievous boys. They hid in the pouch of a kangaroo and started the whole tribe afresh.”

Thus we see here the beginnings of the Wunambal people into a world that appears to recognise the very great age of the landscape, older than the people themselves. The remainder of the story is associated with another site, Wullari or Donkey Creek, and Mowaljarlai waits until they visit there before continuing – since retelling a tale without passing through the very environment where the events are held to take place renders the telling meaningless – reminding Malnic that Dumby had gone to Wojin and his Council of Wandjina, asking them to ‘growl the boys’ in punishment for their mischief:

“When those Wandjinas came, their foot laid a path, they made tracks… At Wullari they gave title to their hosts, the Munmurra mob [a moiety of the Wunambal people], the people who later came to paint here at Donkey Creek. That title is like a seal, stamped on them forever… They represent the history, the Beginning, the journey and the reason of the track. We must pick up everything from a track – animal track, history, painting, images. We must follow it back to learn from the track, to know how to live with it, to pass it on. All this was brought together here at Donkey Creek.”

We are here witness to a powerful and complex mandala of subtle beliefs, highly contextual deeply founded upon journeys within specific landscapes, each journey conferring a sense of custodianship, in a system bearing little resemblance to anything we might recognise in the Western world.

The activities of the wandjina set the prototypes not just for ownership, but for the laws and customs of the people and in the fullness of time, each wandjina completed its journey, arriving at its destination where it painted itself onto the rock. Cowan narrates the deeper meaning of this ending:

“[They] ‘lay down’ in… caves. This ‘lying down’, though it implies death, in reality records the cessation of the wandjinas’ world-creating activities. They disappeared into the rock-face, leaving their images on the wall.”

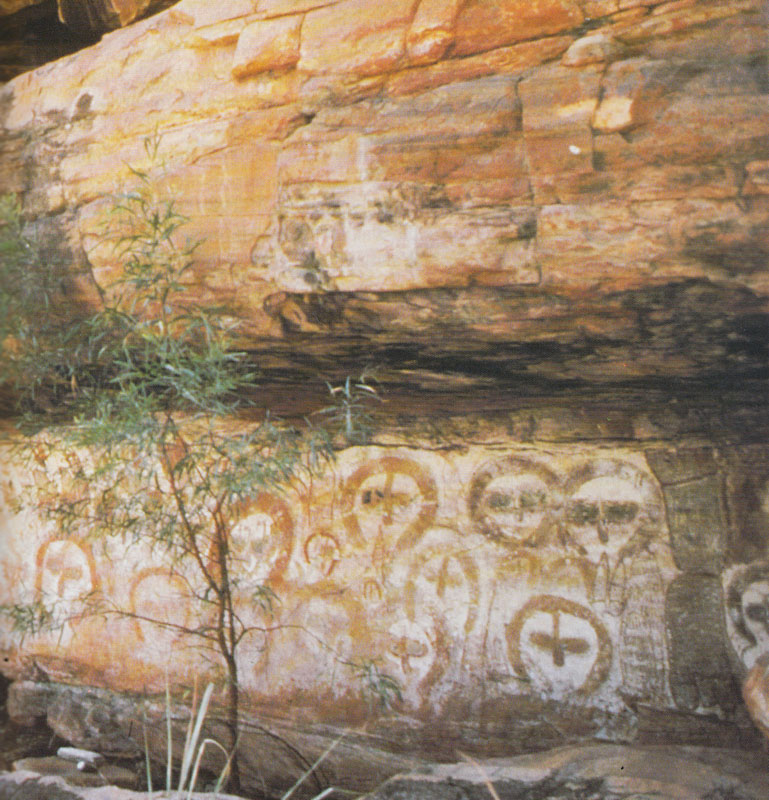

Mowaljarlai & Malnic add additional details to this ‘lying down’, that passing out of this world, each one found a waterhole, a wunggud water where an Earth Snake is believed to reside, through which to leave, and it is notable that each site where wandjina images are painted is associated with a body of water nearby, containing the energies of both the wandjina and the Earth Snake within.

The image of the wandjina conforms strictly to a set of conventions the individual features of which are redolent with meaning. Early wandjina are depicted as full humanoid figures, with mouths, arms and legs, but the typical later phase consists of the head and body only, and wide-staring eyes, surrounded by radial lines of power. These latter features are called the djagarra, and are often combined with rings around the head, representing malngirri, lightning, or various types of clouds from low, rain-laden clouds to high cirro-stratus clouds that signify the movements of the winds.

Most wandjina are depicted without a mouth – as Daisy Utemorrah relates to Malnic: “He has no need of a mouth, he sends his thoughts” – and the line running between the eyes does not represent a nose, but the place where the creative power flows down from the spirit into the world. The lack of a mouth also resonates with the white colour of the face of the wandjina, both of which symbolise mamaa, an immanent sacred power of rock art sites, as Ngarinyin elder Banggal relates to Doring in relation to Ngegamorro, an ancestral wandjina of the Ngarinyin people:

“You can see he has no mouth, you can see all this white thing… it’s beyond our knowledge, it’s very taboo… that’s why we call them mamaa.”

The story of Wallanganda is a particularly powerful one. According to Doring et al, Wallanganda represents “the entire Milky Way, a body of light forming the creator of the earth…” and Mowaljarlai concurs:

“Wallanganda travelled across the countries. As he walked over the soft ground, the soil formed and hardened into rivers, mountains and rocks. He made trees, shrubs and plants for his landscapes. He made all things of nature.”

Mowaljarlai narrates in detail how Wallanganda created humanity, appearing with his chest shrouded in mist and his head encircles by flashes of lightning and clouds of rain:

“Then came the time to make man. 'What shall I do now?' this wandjina said. He was seeing himself alone. He looked down and saw a child moving in a wunggud water [pool]. 'Oh, that is a kid moving,' said the wandjina. He picked us up and put us on his head and took us along – the image of the little fella, the image. Then he saw another picture in the water, a reflection of the wandjina, of himself. And he took some mud and formed the mud. He made man. He built a first man... It was a mould, a blueprint...”

Here is a striking mythical image, of a creator spirit reflecting himself in his creation and the making of a blueprint through which all humans can be created, in Mowaljarlai's words “as spirit individuals dreamed into a woman's womb”. This resonates deeply with the aforementioned idea of the wandjina as a continuously-present humanity expressed in the customs and sacred journeys of the people through the medium of the wunggud water, and Mowaljarlai underscores this in the continuation of the myth in which the first woman is created:

“Then the Creator made woman. He made the woman also from mud, like the man. We are all the same. Najjar [an alternative name for Wallanganda] means ‘same-like, copyright, spit image to himself’, as Wandjina. You can see it in rock art. Man and woman are walking about. The design of their bodies had been laid down on Earth.”

Wallanganda thus opens up an important concept which underlies all wandjina Dreamings, that although their actions took place in Lalai, the beginning of the world, their creative and magical actions are not confined to that primordial period, but are held to be continuously acting through the rock images – and through living human beings – within the field of the present time. This idea is encapsulated in the Wunambal notion of yorro yorro, disclosing a sense of permanent acts of continuous creation. Mowaljarlai makes this point several times to Malnic:

“[Wallanganda’s] deeds are Yorro Yorro, everything on earth brand new and standing up. Yorro Yorro is continual creation and renewal of nature in all its forms. He installed everything, and he gave it life to continue growing…”

“Wandjina put people to tell the story of his Idea. And his Idea became the painting. The land was given and divided out to the people as caretakers to keep his Idea going. People who live today still carry on, because we are still of the same image as that ancestor mob dead-gone before us. Even today we still represent Creation. Yorro Yorro is ongoing, everything standing up alive.”

Here we see a wide-ranging link between the Idea of Creation – the powerful plan of the Creator who creates by “sending his thoughts” in a continuous flow of yorro yorro – the custodianship of the landscape by successive generations of people (another act of yorro yorro) and the images of the wandjina paintings. This image, this Idea, must surely be identical to the Najjar that Mowaljarlai mentions above, the ‘same-like’ which is an alternative name for the creator wandjina Wallanganda himself.

Banggal underscores this to Doring, in a powerful narrative told to him at a sacred water pool near Marranba Bidi, resonating with the notion of wandjina as ‘water people’ and of the emergence of new life as a precise recreation of the primordial actions of Wallaganda:

“This wunggud water here, holy water from wandjina… they made man, everybody, everything… We find children from water, that’s why we’re water people. We spirits hide in the water, come out in the open. We all belong [to] water because wandjina belong [to] water… That is why every man or girl, they come out from each wunggud water, wandjina gives us back… Our spirit come from water because we all come from spirit water…”

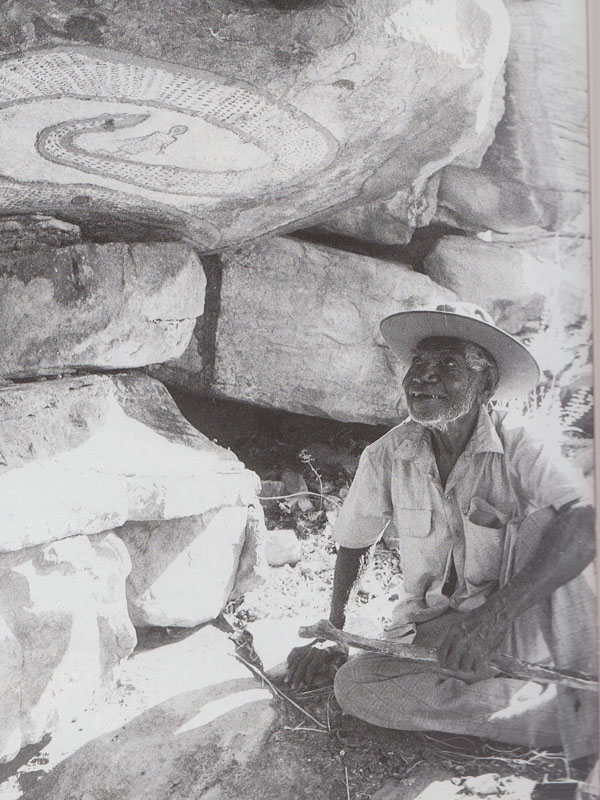

“To retouch a painted Wandjina causes rain, and to paint or retouch figures of animals, birds, reptiles and plants in a Wandjina gallery ensures the increase of the particular species in due season. The painting or retouching is the ritual; it is a sacramental act through which life is mediated to nature and to man.”

We may see this ritual as another act of yorro yorro, and custodianship passes down the generations of lineages whose spirits were born from the wunggud water at each site. Few Western observers have ever witnessed these magical renewals, the acts of profound re-creation likely being too sacred, too mamaa, for outsider eyes, since they ensure the continued preservation and animation of the world – indeed Banggal’s relating of the interrelationship of identity between humans and wandjina, symbolised by the wunggud water, suggests that to recreate these images to ensure the continuous creation of future generations of Wunambal and Ngarinyin people.

It is unclear now in the twenty-first century how many wandjina sites are being actively curated and tended. Rapid cultural changes taking place in the Kimberleys, from missionary activity beginning in the 1930s to the loss of lands to farming and sheep-rearing, along with the only-recently discontinued Australian policy of removing Aboriginal children from their families to attend Western schooling, has led to a profound loss of knowledge. Indeed, the precise locations of several important sites are now no longer known, including most significantly Lejmorro, the site sacred to the Milky Way which includes the image of Wallanganda himself (and hence, why this essay contains no image of this prominent wandjina). Many of the images are fading, since the lineages no longer exist to tend them, or have been forgotten in the drive to acculturate the Aboriginal peoples of the Kimberleys to Western norms, with the sad implication that an age-old cycle of yorro yorro may for some of the wandjina, be in the process of breaking.

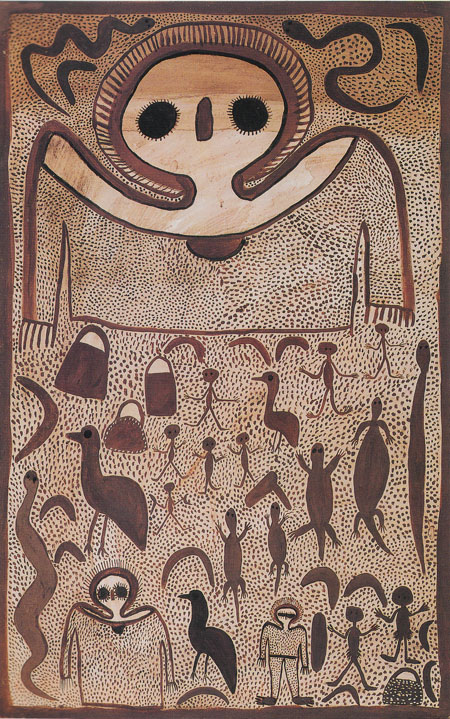

There is, however, hope for the future. The emergence of intense interest in Aboriginal artforms among contemporary galleries in Australia and the wider world has allowed for a resurgence in wandjina painting, this time upon canvas, bark and other materials rather than rock shelter walls. Mowanjum Arts, a collective of Aboriginal artists from all three language groups of the Kimberleys, based near Derby in Western Australia, has since the 1970s sought to promote the culture and continued expression of the wandjina, as has the Waringarri collective based in Kalumburu at the very northern tip of the Kimberley range.

Worora artist at Kalumburu (National Gallery of Victoria)

“Every race of people has a culture to follow. If you lose your culture you are floating... lost. The Mowanjum artists are strong and they know it is their job to pass on their knowledge to young people, to keep the spirit of the Wandjina alive.”

The appearance of an increasing number of books, two of which have greatly informed this essay, in which authentic Aboriginal voices (as opposed to Western interpretive voices) are heard as they travel through the sacred sites of their landscapes, also old much promise for the future. Mowaljarlai himself was eager that his knowledge should be passed to the next generation before he died, and perhaps transmission through books and art will lead to a return, in the fullness of time, to the original rock art sites to partake once again in the profound cycle of continuous creation and image identity of yorro yorro.

But I lost my place

Then I lost my dignity – spirit.

“Once when I walked my country

I was lizard and kangaroo

I was turkey and emu

And the Wandjina walked with me…

“I must remember, I must know

Might be an illusion

That holds me from my country.

“For I am Wunambal

I am lizard and kangaroo

I am turkey and emu

And I am spirit – rock

And I am Wandjina.”

David Mowaljarlai

Jeff Doring, Ngarjno, Ungudman, Banggal & Nyawarra, Gwion Gwion Dulwan Mamaa: Secret and Sacred Pathways of the Ngarinyin Aboriginal People of Australia, Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft, 2000

Susan McCulloch, Contemporary Aboriginal Art: A Guide to the Rebirth of an Ancient Culture, Allen & Unwin, 2001

David Mowaljarlai & Jutta Malnic, Yorro Yorro: Aboriginal Creation and the Renewal of Nature, Inner Traditions, 1993

Australian Stamp & Coin Co Pty, The Aborigines: Early Inhabitants of the ‘Top End’, url: http://www.australianstamp.com/Coin-web/feature/history/abdream.htm, retrieved August 2010

Mowanjum Arts, quote from Donny Woolagoodja on front page of website, url: http://www.mowanjumarts.com/, retrieved December 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed