In many ways, the often cited category of the ‘Palaeolithic cave painting’ is a clumsy term, not least because the phrase actually represents several widely divergent traditions visible in three discrete time periods (the early-to-mid Aurignacian, the Gravettian-Solutrean and the Magdalenian) stretching across nearly thirty thousand years of the European Upper Palaeolithic. As such, it is hardly likely that the same ritual functions and cultural imports of the paintings would have persisted unchanged for such a long time period – indeed important clues of these changes can be gleaned from the architectural spaces of the caves themselves and the siting of the art within them, as well as from the interactions between the cave sites, particularly in the latter two periods.

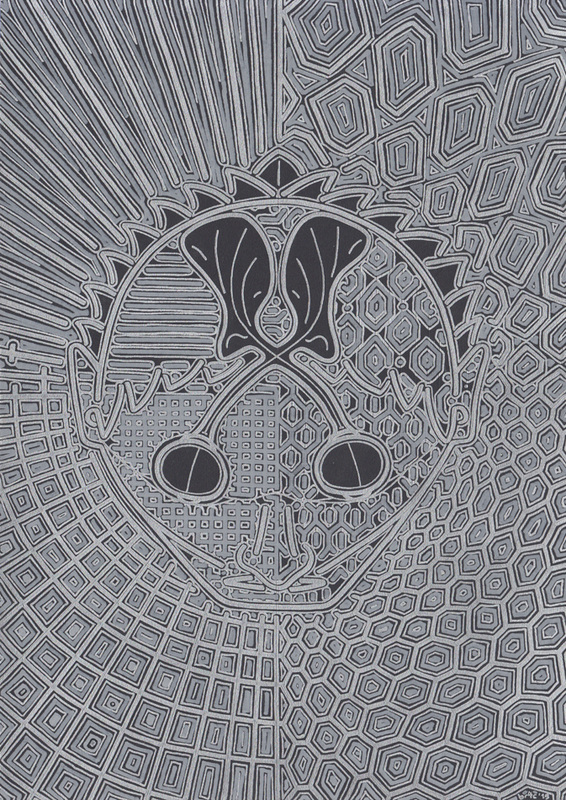

There are also huge changes within the art itself, and the famous images of animals of the Eurasian Steppe represent only one strand of a rich set of traditions whose varieties and subtleties are easily missed from within a casual purview. In the earliest periods, dots and tectiforms of unknown meaning seem to predominate, but by the late Aurignacian (30-28kYa B.P.) the familiar images of bison, cave lions, deer and others take centre stage, with human-animal hybrids making occasional appearances. In the Magdalenian, abstract claviforms accompany animal images but the usage of the cave itself seems to be transformed into public and private spheres in a manner not seen previously.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed