|

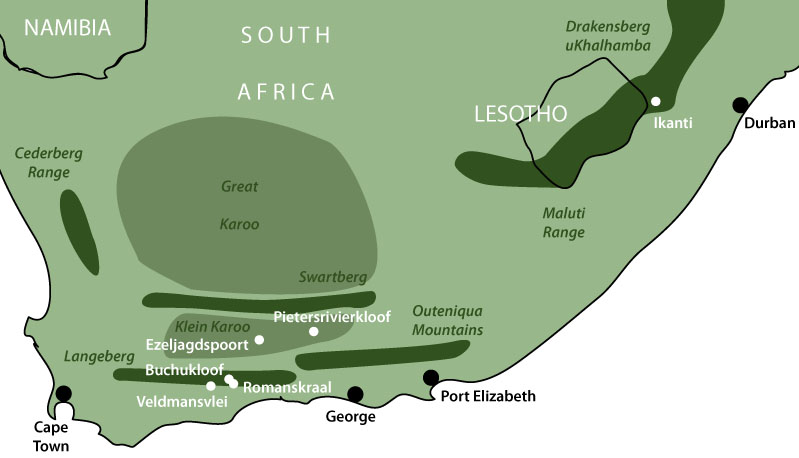

Let’s start as we mean to go on with the Archaic Visions reboot, and open the first strand with which this blog will continue – Rock Art of Southern Africa. Here I present rather a long article, the first in this series, which provides an introduction to Bushman Rock Art and Culture. It is rather academic in style in places, and the intention is to present to my readers a style of art and painting which shares next to nothing with familiar Western or Oriental art traditions in its method, approach, interconnection with religious and ritual practices, and even how it interacts with the environment in which it is found. If at times this series of articles seems to go into excessive detail, then this only reflects my genuine enthusiasm for Bushman rock art and engravings, and my deeply-held desire to understand, and to see these remarkable painted images through the eyes of the remarkable people who painted them. In this spirit, let’s begin this long, winding and hopefully fascinating journey into the world of the Southern African hunter-gatherer… Southern Africa is home to one of the most fascinating, and yet least well-known, art traditions in the world. Running in a near continuous line of rock shelters from the Cederberg in the West to the Drakensberg-uKhahlamba mountain range in the east, as well as across other sites in the subcontinent, the rock paintings and engravings of the indigenous hunter gatherer peoples of South Africa and beyond – the Bushman, San, or Khoi-San peoples and their cultural ancestors – represents one of humanity’s most distinctive art styles and, until its extinction some 150 to 200 years ago, one of the longest running.

5 Comments

The notion that the cave paintings of Southern France and Northern Spain during the Upper Palaeolithic were painted by shamans is so ubiquitous in the visionary community as well as other circles as to effectively have become a kind of dogma. In archaeology, however, in recent years, this idea has come to be challenged in favour of a more nuanced view, and many of the images previously thought as shamanic now partake in a wider understanding of what little we can know of the Palaeolithic cultural context, the function of the art itself and of human creative and ritual behaviours. In my many years of studies in Palaeolithic artforms, there seems to me now only a handful of images with unambiguously shamanic elements. One such painting might be the famous Bird Man of Lascaux, but as we shall see, despite the shamanic nature of this image, it is not exclusively so, and partakes of wider cultural forms as much as any other image...

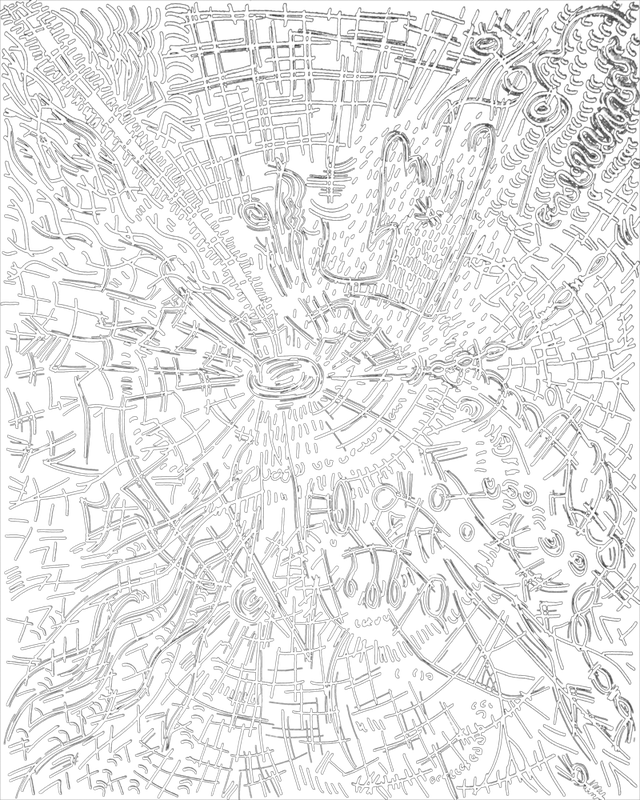

In many ways, the often cited category of the ‘Palaeolithic cave painting’ is a clumsy term, not least because the phrase actually represents several widely divergent traditions visible in three discrete time periods (the early-to-mid Aurignacian, the Gravettian-Solutrean and the Magdalenian) stretching across nearly thirty thousand years of the European Upper Palaeolithic. As such, it is hardly likely that the same ritual functions and cultural imports of the paintings would have persisted unchanged for such a long time period – indeed important clues of these changes can be gleaned from the architectural spaces of the caves themselves and the siting of the art within them, as well as from the interactions between the cave sites, particularly in the latter two periods. There are also huge changes within the art itself, and the famous images of animals of the Eurasian Steppe represent only one strand of a rich set of traditions whose varieties and subtleties are easily missed from within a casual purview. In the earliest periods, dots and tectiforms of unknown meaning seem to predominate, but by the late Aurignacian (30-28kYa B.P.) the familiar images of bison, cave lions, deer and others take centre stage, with human-animal hybrids making occasional appearances. In the Magdalenian, abstract claviforms accompany animal images but the usage of the cave itself seems to be transformed into public and private spheres in a manner not seen previously. I have suffered – if that is the right word – from migraines since I was a child, and I am lucky – again, if that is the right word – enough to be one of the twenty percent of migraineurs who experience both the visual aura that precedes the migraine as well as the visionary aspects during. Some of my most powerful childhood memories are of sudden dysphoria and immanent sensations of fractured consciousness which are the hallmarks of visionary experience engendered by migraines, and in a sense, I view them now as part of a natural feature of my neurology. This essay takes in a personal and prehistoric view of this important but challenging aspect of my life.

In his Manifesto of Visionary Art, artist and author Laurence Caruana elucidates a near-exhaustive list of the sources and inspirations from which Visionary Art can spring. It is worth quoting: “...the sources of Visionary Experience are many and varied: dreams, lucid dreams, nightmares, hypnogogic images, waking dreams, trance states... hypnotic states, illness, near-death experiences, shamanic vision-quests, meditation... madness... day-dreaming, fantasy, the imagination, inspiration, visitation, revelation, spontaneous visions, psychedelics, reading and... the metanoic experiences brought on by Visionary Art itself.” In the Mexico Room of the British Museum, London, are three lintels (two originals, one archival cast) from the Classic Maya city of Yaxchilan in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. These exceptionally-crafted public artworks depict a fascinating ritual to evoke a Divine Ancestor, thus broadcasting both a sense of royal propaganda and of sacred intimacy, but it is the image of visionary beholding vision which is particularly interesting, disclosing an archaic expression to the scene. The Classic Maya city of Yaxchilan is one of several archaeological sites located in close proximity to the Usumacinta River along the border between Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas. It sits just on the Mexican side in a meander of the river, likely a vital spot since the river passed through the city and allowed the rulers to control – and perhaps impose duties upon – the trade and river traffic moving from the mountains towards lowland cities such as Palenque.

Anciently known as Pa' Chan ('Broken Sky') or Siyaj Chan ('Born from the Sky'), Yaxchilan's documented history begins around the mid 4th century AD but the city flourished in the Late Classic period (6th-9th centuries AD), dominating nearby Bonampak and the Usumacinta corridor, as well as establishing rivalries with both Piedras Negras and Palenque downstream. |

ARCHAIC VISIONS

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed