Anciently known as Pa' Chan ('Broken Sky') or Siyaj Chan ('Born from the Sky'), Yaxchilan's documented history begins around the mid 4th century AD but the city flourished in the Late Classic period (6th-9th centuries AD), dominating nearby Bonampak and the Usumacinta corridor, as well as establishing rivalries with both Piedras Negras and Palenque downstream.

Each surviving lintel has been numbered by archaeologists: the Lintels numbered 24, 25 and 26 are the ones which interest us here, located above the doorframes of Structure 23. This building was erected to mark the re-founding of the city under Itzamnaaj B'alam II and the lintels served as a sacred mythical precedent authorising the legitimacy of his rule and that of his subsequent dynasty. It was also considered to be the yotot, or royal house of the queen.

The three lintels, when viewed together, form a narrative of a ritual performed not by Itzamnaaj B'alam II, but by his wife, Lady K'abal Xok – it is a curious feature here and in another set of Yaxchilan lintels that despite the male-dominated Classic Maya culture, it is the women who appear to be the visionaries. The ritual depicted moves from a scene of blood-letting sacrifice, perhaps preparatory to the vision, to one of Lady K'abal Xok beholding a vision of a royal ancestor, perhaps the founder of her line or the line of her husband the king, before proceeding to an obscure ending in which she seems to arm him for battle or perhaps authorise his rule. Let us consider each lintel in turn.

Itzamnaaj B'alam illuminates Lady K'abal Xok's bloodletting ritual

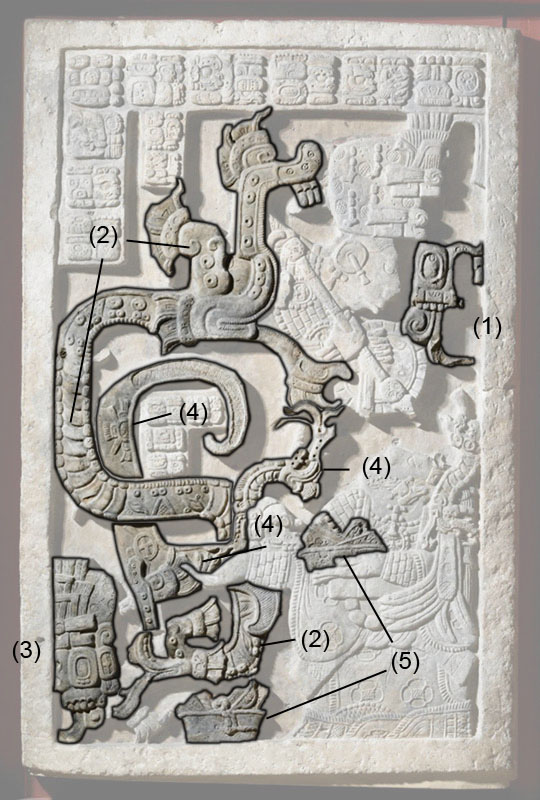

Now dressed in even finer garments decorated with flower motifs and bearing both the basket of blood-soaked papers along with a serpent bar decorated with a skull in her hands, Lady K'abal Xok gazes upwards with shamanic intensity at the vision she has conjured. At her feet lies the basket of papers, and it is from these that a double-headed Vision Serpent emerges, winding its way up the left hand side of the lintel image, part-snake, part-centipede, before opening the jaws of its upper head to reveal Yoaat B'alam, the First-Seated Lord and ancestral founder of the Yaxchilan royal line. The lower jaws contain a standard representation of Chac, the Mayan Storm God.

Lady K'abal Xok beholds a vision of a Royal Ancestor

These words lend an androgynous sense to the face of the ancestor, and ambiguously suggest that the figure so envisioned represents the combined ancestral spirits of both of the king's and queen's houses. Nonetheless, this is a stunning and profound artwork of visionary intensity and its fuller significance will be discussed in a moment.

Lady K'abal Xok hands a jaguar mask to Itzamnaaj B'alam

Vogt narrates that among the contemporary Tzotzil Maya, it is believed that blood conveys not merely life but ch'ulel (Classic Maya ch'ul or k'ul). This is a complex word generally referring to the soul of a person, but it can also mean 'to dream or envision' and 'holy or sacred', and given that the soul has several parts, it often has a sense of the essence of the soul rather than the soul itself. In Classic Maya and colonial Yucatec texts we see a parallel concept in the itz, a sacred substance that was held to manifest in a variety of forms from dew, sweat, milk, tears, and tree sap to melted wax, rust, resin or incense. It was often called yitz k'an 'the itz of the sky', disclosing its nature as the ch'ul of the gods, and thus where ch'ul can be considered human and earthly, itz is divine and cosmic: indeed it has been termed 'cosmic sap'.

According to Freidel and Schele, the link between blood-letting and the apparition of a deity was that "...when the ancient Maya let blood, they were feeding the gods their ch'ul and giving of their souls..." and that at least one of the aims of this was to enter trance and achieve direct communion with the gods. They also note that the Classic Maya word itzam, 'one who manipulates itz' is a term for shaman: Itzamnaaj B'alam II's name thus resonates strongly with a royal prerogative over this sacred substance and the interaction between ch'ul and itz that blood-letting implies.

The name of the god presiding over such rituals was K'awiil, an aspect of the storm god Chac, principal among whose functions was to be present during religious activities and to inform royal power. His name means 'sustenance' in several Maya languages in the colonial period (including Yucatec and K'iche'), referring to any precious substance, whether plant, food or bodily fluid, given freely to the divine, but may have meant 'powerful one' in the Classic Maya language. This latter meaning functioned as a title of Chac, and K'awiil appears to have been in part the personification of lightning. Both of these titles also refer to the ritual at hand – blood-letting and an apparition of an ancestor masked as 'powerful' Chac.

As Freidel and Schele note: “K'awiil was a nexus for powerful phenomena in the Classic Maya world that conjoined spirit to body and sustenance to sacrifice,” and in so perceiving this, the artesans took great care to implicitly depict K'awiil in several places on Lintel 25.

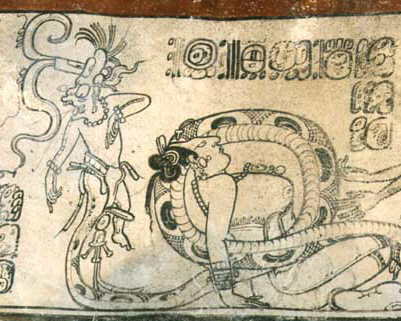

K'awiil was often depicted with one leg in the form of a serpent, simultaneously representing the snakelike action of lightning but also the overwhelming sensations of bodily envelopment during the course of trance and vision. In one famous image from a Classic Maya vase, a woman is shown entwined and entranced in K'awiil's serpent leg, although the vision she is experiencing is not shown. Freidel and Schele make a convincing case that the serpent represents the way of K'awiil, a word ubiquitous throughout modern Maya languages to refer to an animating presence (Yucatec way, wayob), dreaming aspect of the soul (Tzotzil vayijel) or a shapeshifting spiritual being associated with great shamans or sorcerors (Lacadon ah way) as well as verbs with a range of meanings from 'transfigure, enchant' to 'sleep, dream'.

Classic Maya vase, provenance not found

The Vision Serpent, the way of K'awiil, dominates the scene, and its double-head mirrors the serpent bar that she grasps during her vision. That Vision Serpents come to disclose wisdom is underscored by Eric Thompson (as reported in Freidel, Schele & Parker) in his narration of an early twentieth century shamanic initiation among the Q'eqchi:

“At the end of the period the initiate is sent to meet Kisin...[a Q'eqchi deity who] takes the form of a large snake called Ochcan... When the initiate and Ochcan meet face to face, the latter rears up on his tail and, approaching the initiate till their faces are almost touching, puts his tongue in the initiate's mouth. In this manner, he communicates the final mysteries...”

This description closely mirrors the scene on Lintel 25, the gaze of intimacy between the two Classic Maya subjects powerfully illustrating the face-to-face interaction of the modern Q'eqchi initiate. The name 'Ochcan' is revealing: it occurs in Classic period inscriptions too and is perhaps better expressed as Och K'an, 'enter the sky', that is to say, the world of the gods. Here, then, is a clear expression of the Maya understanding of the Vision Serpent as portal, a conduit through which the visionary could enter the world of the gods, or through which the gods could enter this earthly realm.

(1) Mask of Aj K'ak' O Chaak, with which K'awiil is identified

(2) Double-headed Vision Serpent, the way of K'awiil

(3) A second Chac image

(4) Serpent bar, from which K'awiil is often seen emerging

(5) Basket of blood-soaked papers or cloth - K'awiil as 'sustenance'

The persistence of the word k'an, 'sky', here reveals an astronomical dynamic to the proceedings, since it is held by Schele that the double-headed Vision Serpent (featured here also in the serpent bar that Lady K'abal Xok holds) draped across the World Tree in Classic Maya iconography represents the ecliptic, the celestial plane through which the Sun, moon and planets move, all of which were envisaged as deities.

Thus we have here access, not merely to a simple vision-inducing ritual invoking royal power, but a complex of perceptual experiences that render an authentic Maya cosmos in microcosm. Lady K'abal Xok gazes not merely into the face of a serpent or ancestor, but into the very highest levels of the world of the gods moving through the sky, as she engages in actions of reciprocal sustenance through the sacrifice of her blood-ch'ul and its transformation into cosmic sap as food for the gods. This discloses a wholly different relation to the sacred than anything in the West from the past two thousand years, and the notion that a deity can be conjured to appear by a woman of royal prestige and spiritual power through the feeding of her own essence is a powerful and archaic image.

The notion of serpent as sacred portal is perhaps unusual (though powerfully descriptive to those who have experienced such visionary trances!) but the expression of transcendence in this mythical image resonates with traditions of divine serpents throughout the non-Occidental world.

There is also a subtle warlike implication here: the name waxaklahun ub'ah k'an as an essence of the god Chac in his warrior aspect seems to inform the actions of the final image in the sequence, and perhaps Itzamnaaj B'alam is indeed being armed by his wife after a visionary intercession with their ancestors for a successful outcome to the exploit, which is unrecorded elsewhere but given the commissioning of these lintels, must have been successful.

Equally profound, however, on Lintel 25 is a meta-method of expressing visionary experience not commonly seen in contemporary artworks, that of Visionary Beholding Vision, a ubiquitous and pan-cultural archaic device used to disclose sacred intimacy. The present author has utilised this style several times in various works, as do a few others (Pablo Amaringo is a notable and well-known example) and it is hoped that the dissemination of images such as these will bring this device into a wider understanding.

Finally, Miller reports in her review of Mesoamerican art that traces of traces of red, yellow and green polychrome have been found on Lintel 25 and others, confirming what had long been suspected: that the Yaxchilan reliefs were once brightly painted. Such colours must have lent an even more dazzling visionary intensity in their original forms than the surviving images that have come down to us, an intensity we can now only imagine, or attempt to experience ourselves through our own trancelike voyages through Vision Serpents into the reciprocal world of the Mayan ancestors.

Wak Tuun envisions a Royal Ancestor

The text tells us the apparition is of the Waterlily Serpent, another way of K'awiil, one associated with the psychoactive Nymphaea ampla lily which may have been added to the balche' drink so as to quicken the visions, and which may be the flowers featured on Lady K'abal Xok's garments on Lintel 25. The ancestor conjured here is named as Lady Baahkab, whose identity is unknown.

This raises a question: it seems clear that the ancestral spirit Lady Baahkab does not come from the more well-known lineage begun by Yoaat B'alam, and which included Itzamnaaj B'alam and his son Yaxun B'alam as descendants, but perhaps from the notable Yaxchilan family the Ik', of which Wak Tuun was a member (although it should be noted she may have come from Motul de San Jose, another polity some 100km to the east of Yaxchilan). It appears this female visionary is conjuring one of her own ancestors in this image rather than one of the king's, much as Lady K'abal Xok may have done, and again, in the context of a male-dominated Classic Maya society, it needs to be asked why, at Yaxchilan and elsewhere, do we principally see women, and not men, acting as the visionaries?

So far in my researches, I have not been able to uncover a satisfying answer to this fascinating question beyond generalisations which may not pertain accurately to a Mayan cultural context. Likely it has been addressed by archaeologists and anthropologists working in the field, and I hope to come across that research in due course!

Barbara W. Fash and Ian Graham (eds.), Yaxchilan Lintels 15, 25 & 26, in Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 1968-2004, urls: https://www.peabody.harvard.edu/CMHI/detail.php?num=15&site=Yaxchilan&, http://www.peabody.harvard.edu/CMHI/detail.php?num=25&site=Yaxchilan&, and http://www.peabody.harvard.edu/CMHI/detail.php?num=26&site=Yaxchilan& , retrieved April 2014

William L. Fash, Alexandre Tokovinie and Barbara W. Fash, The House of Fire in Teotihuacan and its Legacy in Mesoamerica, Harvard, 2009, url: http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic1173827.files/Fash_New%20Fire_2009.pdf , retrieved April 2014

David Friedel, Linda Schele and Joy Parker, Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path, HarperCollins (Perennial), 1993

Scott A. J. Johnson, Translating Maya Hieroglyphs, Univeristy of Oklahoma, 2013

Justin Kerr, The Maya Vase Book Vol. 6, Kerr Associates, 2001

Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya, Thames & Hudson, 2000

Mary Ellen Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec, Thames & Hudson, 1996

Mary Ellen Miller, Mayan Art and Architecture, Thames & Hudson, 1999

John Montgomery, A Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs, Hippocrene Books, 2002 – updated version online via url: http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/dictionary/montgomery/ , retrieved Sep 2013

Linda Schele and Mary Ellen Miller, Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art, Thames & Hudson, 1992

Joshua T. Schnell, The Sacred Kan: A Study on Classic Period Maya Serpent Deities and the Postclassic Feathered Serpent, Michigan State University, 2013

Evon Z. Vogt, Tortillas for the Gods: A Symbolic Analysis of Zinacanteco Rituals, Harvard University Press, 1976

RSS Feed

RSS Feed