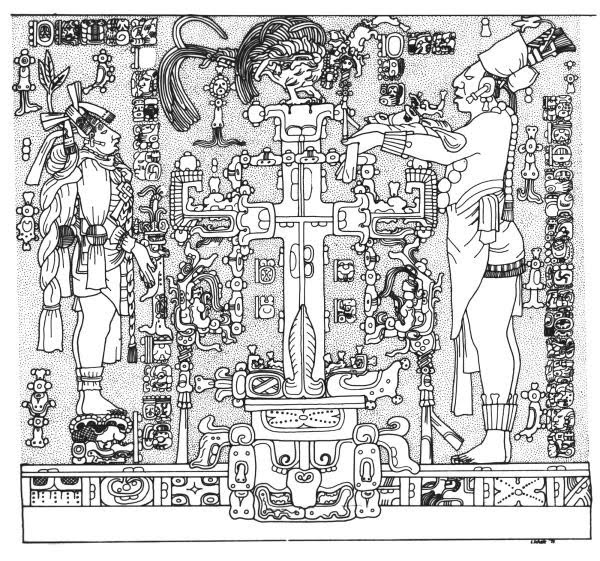

It has long been known that in the Classic Maya language of the inscriptions, the word for 'sky', chan, is often expressed or replaced with glyphs for 'four' or 'snake'. This wordplay, which has persisted in many modern Mayan languages across the centuries, happens to illuminate several previously-impenetrable Mayan images with meaning. Thus, for example the Classic Maya image of the World Tree as being bedecked with foliage with its cross like central bar represented as a double-headed serpent makes more sense when one considers that the Classic Maya translation of 'world tree' was wakah chan.

|

Across the various Mayan languages, whether ancient, colonial or modern, there exists a nexus of words and wordplays centred on the sounds chan, kan, k'an and ka'an which reveal interesting dimensions to Mayan conceptions of the sky. This wordplay symmetry is broken however in Tzotzil, a language of the highlands of Chiapas, where the word for sky is vinajel, but it nonetheless demonstrates something fascinating about the Mayan cosmovision.

It has long been known that in the Classic Maya language of the inscriptions, the word for 'sky', chan, is often expressed or replaced with glyphs for 'four' or 'snake'. This wordplay, which has persisted in many modern Mayan languages across the centuries, happens to illuminate several previously-impenetrable Mayan images with meaning. Thus, for example the Classic Maya image of the World Tree as being bedecked with foliage with its cross like central bar represented as a double-headed serpent makes more sense when one considers that the Classic Maya translation of 'world tree' was wakah chan.

0 Comments

The Land of the Ever-Living is a perennial image across the world's mythologies, and Celtic traditions of northwest Europe are no exception. Indeed in surviving Welsh and British traditions, journeys to such lands form the essential theme of the majority of legends, the most famous of which is the Arthurian Avalon. First recorded in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, Avalon discloses a much more ancient image than the High Middle Age date of Monmouth's account would imply.

The Otherworld is a continuously-appearing theme in Celtic mythology: in the medieval Welsh collection of myths entitled the Mabinogion alone, we see a journey to Annwn, the Land of the Ever-Living in the local traditions of Dyfed; the misty enchanted realm of Llwyd ap Cil Coed in which the protagonists are imprisoned; and a sailing to Ireland, presented as a magical land. Other poems tell of fateful journeys to Caer Sidi – Mound Fortress – from which only seven return alive, and of Ceridwen's island, from which only Taliesin was able to escape.

*** *** *** The language of this dedicatory prayer is Tzotzil - li batz'i k'op e, 'the true words' - a Mayan language of the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. It follows a traditional pattern of speaking to saints and ancestors, although the words chosen are my own. It is offered with sincerity to our collective ancestral humanity as I begin this initiative.

|

ARCHAIC VISIONS

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed