The Otherworld is a continuously-appearing theme in Celtic mythology: in the medieval Welsh collection of myths entitled the Mabinogion alone, we see a journey to Annwn, the Land of the Ever-Living in the local traditions of Dyfed; the misty enchanted realm of Llwyd ap Cil Coed in which the protagonists are imprisoned; and a sailing to Ireland, presented as a magical land. Other poems tell of fateful journeys to Caer Sidi – Mound Fortress – from which only seven return alive, and of Ceridwen's island, from which only Taliesin was able to escape.

The name Avalon – in Welsh ynys afallon 'island of apples', an image redolent of among others the Greek Garden of Hesperides – can be considered synonymous with Annwn, Caer Sidi and others, and while the medieval descriptions of Avalon – especially Monmouth's – are deeply influential on later traditions, it is illuminating to step backwards into more archaic Romano-British traditions to reconstruct earlier forms of the mytheme. Works such as the Mabinogion and the Preiddeu Annwn are useful in this regard.

the prison of Gweir

in the Mound Fortress [Caer Sidi]...

“No one before him went into it,

into the heavy grey-blue chain;

a faithful servant it held.

And before the Spoils of Annwn,

he bitterly sang...”

“My poetry,

from the cauldron it was uttered.

From the breath of nine maidens

was it [the cauldron fire] kindled

“The cauldron of the chief of Annwn,

what is its fashion?

A dark ridge around its border and pearls.

It does not boil the food of a coward...

“And before the door of hell,

lamps burned...”

Continuing through the poem, the Otherworld is given several names which reveal further details: we see Annwn called the Mound Fortress (Caer Sidi), the Fortress of Mead-Drunkenness (Caer Fedwit), the Fortress of Hardness (Caer Rigor), the Glass Fortress (Caer Wydyr) and God's Peak (Caer Fandwy), and as mentioned above, of the three shipfuls of men, only seven returned alive. The etymology of the name Annwn, from annwfn or annwfyn 'not-world', is also revealing, and the emerging picture is one of an island beyond this world, filled with great treasures as well as arduous tests, where the brave may celebrate with mead and wise song. But for those whom, as Gweir sings later, are 'men of failing courage', imprisonment or death awaits.

“...once inside he [Pryderi] could see neither man nor beast, nor boar nor dogs, nor house nor dwelling; what he did see, as if in the middle of the fortress, was a fountain with a marble stone round it, and a golden bowl fastened to four chains, the bowl set over a marble slab and the chains extending upwards so that he could see no end to them. Ecstatic over the beauty of the gold and the fine craftsmanship of the bowl he walked over to the vessel and grasped it, but as soon as he did so his hands stuck to the bowl and his feet to the slab he was standing on, and his speech was taken so that he could not say a single word. There he stood.”

Manawydan returns home to his wife Rhiannon, who berates his cowardice in not entering the fortress to seek news of Pryderi. She goes at once to the fortress and is herself imprisoned. With a rumble of thunder, the fortress then disappears, and Pryderi and Rhiannon with it. It is only when the land's enchantment and the magic of the Otherworldly fortress are revealed as the work of Llwyd ap Cil Coed that the two are returned.

The imagery is familiar – a strange fortress containing a beautiful bowl, chains and a prisoner, although the presence of Rhiannon here is interesting, as she is Pryderi's mother as well as Manawydan's wife – this image of mother and son in the Otherworld will be seen to have relevance later. The dynamic of Pryderi's ecstasy also introduced here is at variance to the fateful voyage in Preiddeu Annwn, and while Gweir sings mournfully, Pryderi is silent. Elsewhere we learn of Pryderi's vanity, a weakness which may explain why the Otherworld robs him of his voice.

The name Llwyd ap Cil Coed ('grey-blue, son of the depths of the woods') provides an interesting liminal aspect to this image. We perhaps have here a vestigial trickster of the wild woods: in additions to the enchantment in this tale, in Culhwch and Olwen, Llwyd steals a cauldron from Ireland and takes it to Dyfed – perhaps this was originally a prequel to the tale narrated here, or one of a series of episodes in a now-lost epic concerning Llwyd's life. His given name also resonates with the chains in Preiddeu Annwn, and indeed with the Greek hero Glaukos ('grey-blue'), a watery underworld deity of transformations.

All of these characteristics chime well with the Avalon as an enchanted island fortress holding a captive or king, and perhaps presided over by a liminal trickster figure: Monmouth's Morgan le Fay bears profound resonance with Llwyd ap Cil Coed, and as the chieftain of nine sisters suggests the nine maidens tending the cauldron in Preiddeu Annwn. But whereas Annwn is sited in several places, but particularly in Dyfed, Avalon bears a persistent identification with Glastonbury. We have Gerallt Gymro (Gerard of Wales) as the most likely source of this in his Liber de Principis Instructione:

“What is now known as Glastonbury used, in ancient times, to be called the Isle of Avalon. It is virtually an island, for it is completely surrounded by marshlands. In Welsh it is called 'Ynys Avallon', which means the Island of Apples... Years ago the district had also been called 'Ynys Gutrin' in Welsh, that is the Island of Glass, and from these words the invading Saxons later coined the place-name Glastonbury”

The name Ynys Gutrin is highly suggestive (gutrin being a variant form of wydryn or gwydryn, from gwydr 'glass' – compare Caer Wydyr above) that the area around Glastonbury was considered precisely the kind of Otherworld described in the Preiddeu Annwn. Glastonbury Tor as an island rising above the waters, and the venerable age of Grail legends in the region, all point to a fairly secure identification of Avalon with Glastonbury. It remains to be seen if the millennial promise that Arthur would return was a Christianising influence, or whether an original Romano-British prophecy concerning the Otherworldly prisoner Gweir or Pryderi chimed with both later Arthurian and later Christian traditions.

However, there are other candidates for the identification. In Irish epics, we hear of Emain Ablach ('Fortress of the Apples'), a paradisical Otherworld ruled over by the sea god Manannan mac Lir (whose Welsh equivalent is Manawydan) and it is well known that the Manx name of the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea – Mannin – is derived from the name of the god.

There is also the hillfort called Caer Afallach, surely a Welsh equivalent of the Irish name, in the northeast of the county of Gwynedd in Wales, which bears several other related toponyms, among them Dinas Bran, 'the city of Bran', another Otherworldly figure from the Mabinogion. David Dom makes a convincing case to site Avalon in this locale.

Such are the early medieval and native Welsh traditions: there is an essential unity in them, but the images have been dispersed somewhat across several stories and a number of different characters. To regress further backwards in time, in pursuit of this unity, and also to reconcile some of the competing ideas and identifications, it is necessary to take a more archaic standpoint, one in which the prevailing Western/Christian view of myth and history enfolded in the legends that have come down to us is moved aside to allow a Romano-British flavour to enter our considerations.

Our contemporary Western religious tradition (and the historical medieval one) is based on Christianity and thus takes a fundamentally different view of cosmos and history than most non-Abrahamic religious cultures, one which Eliade states is based not upon ritual re-enactment of primordiality but upon a single set of events that took place in historical time at a particular locale. For Christians this is the life and death of Jesus in Jerusalem and the Holy Land: Jerusalem behaves in our tradition as a specific real place in Israel, and the time period of Jesus' life as one which is now irrevocably closed to us, history having moved on. This is a radically different understanding to the archaic view, which would understand the Christian perspective as pertaining to the particular rather than the primordial, and as being somewhat opaque to transcendence.

The archaic view, on the other hand, recognises the permanent presence of the primordial and the transcendent in parallel to, and regularly erupting into, mundane space and time. Such eruptions occur during religious rituals, or in liminal and sacred places, in which the particular place, time or ritual enactment is perceived as the image of the primordial, or as the exemplary behaviour of mythical characters as their legend unfolds. In this view, Jerusalem can be anywhere it is ritually re-enacted, or indeed sited in any topology where a 'city of seven hills' might imaginatively exist, and the events of Jesus' life and death re-enter mundane time in any moment they are recalled. One place thus becomes all-place. A devotee undergoing crucifixion does not merely re-enact, but becomes a Christlike figure in this understanding. This is the essence of Eliade's idea of the Eternal Return, and it is profoundly useful for our present topic.

(We may note, in passing, that the Eternal Return is also fundamentally a visionary view. Consider in connection to the above the poet William Blake's words: “...And we shall build Jerusalem in England's green and pleasant land.”)

It is clear that the particular and pseudo-historical narrative styles of the medieval myths mean that this view cannot be applied to them, but any underlying Romano-British and Iron Age (pre-Roman) survivals may be seen through this archaic lens. Pre- and early Christian Celts did not partake of such historically-bound experiences: indeed from evidence of deity names and sacred sites that we have, ancient Britons appear to have been particularly conservative in this regard.

Green has suggested that Celtic deities functioned more like localised genius loci or spirits of place rather than deities in the sense (whether Greco-Roman or Abrahamic) that we would customarily understand them. This aspect is seen most clear when one considers the names of many of the Romano-British deities, the majority of which are seen only in single attestations associated with individual locales.

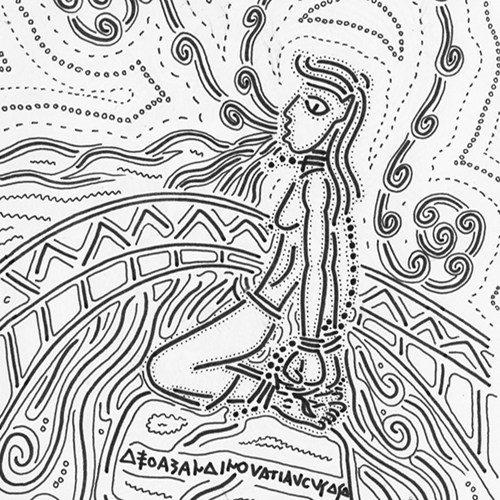

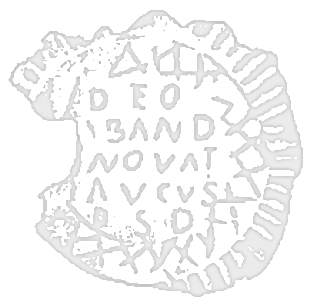

There is for example the inscription to the god Abandinus on a bronze feather found in Cambridgeshire. Only attested from one site, his name appears to be derived from a combination of two proto-Celtic words: *abo(n) 'river' and *bhend 'sing, call out' – 'he who sings or calls out at the river' perhaps, a fine name for a genius loci, and one which appears to disclose hints of a direct visionary experience. One can easily imagine a hunter or fisher (perhaps the Vatiaucus mentioned in the inscription) 'discovering' the deity by hearing his song unbidden by the waters, and such an experience might explain why Abandinus is only found in this single locale. This image also incidentally recalls Gweir and his Otherworldly song emerging from Annwn.

“To the god Abandinus, Vatiaucus offered (this) at his own expense”

Facsimile of inscription to Abandinus, Godmanchester, Cambridgeshire

We see precisely the same lexical structure – though without a gendered ending – in the name Avalon, derived from afal 'apple', and while no Romano-British deity names *Avalonos or *Avalona are attested, the associated Welsh word afallach was used as a name for several proto-historical Romano-British chieftains. The semantic similarity suggests a perceptual similarity here: Avalon in a Romano-British context can perhaps be considered not as a specific locale or to refer to a specific event in history, but as a sacred experience of particular landscape forms, a spirit of place associated with islands of the liminal and the mystical.

In view of the Eternal Return, we might suggest that Avalon once represented any such locale where the boundary between the worlds was thin, attached to many places with similar topography, and imagined similarly as islands surrounded by water in which a fortress (whether conceived as a medieval castle or Iron Age hillfort construction) containing a blessed prisoner was situated. Here we have a more transcendent notion: whether the 'true' Avalon was situated in Glastonbury, Gwynedd or anywhere else is not as important as the experience of Avalon as a liminal place of transformations, and in so considering, the Avalonian image moves from idle legend to true mytheme.

It is likely too that the identity of the captive was just as liquidly perceived: there may have been no 'original' prisoner from whom the medieval traditions derived. Instead local Romano-British tribes may have have adapted the mythical image to their own local deities. Developing from this, some individuals particularly adept in mythical or magical thinking may have sought to create a new Avalon, perhaps when moving the clan to a new location, using ritual and the kind of trickster enchantments employed by Llwyd ap Cil Coed to engender a new liminal place which would authorise and inform the new landscape in a mythical manner.

But the Wild Trickster or Mistress of the Otherworld images are nonetheless persistent: Morgan le Fey, Rhiannon and Llwyd ap Cil Coed bear considerable resemblance aside from the difference of Llwyd's gender, and it is tempting to consider Rhiannon's eagerness to enter the enchanted fortress as a remnant of her identity as Rigantona – Great Queen, possibly of the Otherworld. Rhiannon certainly has a good number of Otherwordly and magical attributes, not least her association with the Adar Rhiannon, three birds whose song can wake the dead and lull the living to sleep.

This notion of Maponos ap Dea Matrona, 'Son, son of Mother Goddess', in the Otherworld is perhaps the only glimpse of a genuinely Iron Age British Celtic image that survives from the Avalon/Annwn mytheme. We can well imagine Rhiannon and Morgan le Fey (and possibly, in masculised form, Llwyd ap Cil Coed) as local survivals of Dea Matrona into the historical period, and Maponos as the lost son.

No one will be afflicted with disease or old age that may be in it.

It is known to Manawydan and Pryderi.

“Three utterances, around the fire, will he sing before it,

And around its borders are the streams of the ocean.

And the fruitful fountain above it

Is sweeter than white wine the liquor therein.

“And when I shall have worshipped thee, Most High, before the earth,

May I be found in covenant with thee...”

David Dom, The Origins of Avalon, 2005, url: http://www.traditionalharp.co.uk/Caer_Feddwyd/articles/origins%20of%20avalon.htm , retrieved October 2011

Mircea Eliade, The Myth Of The Eternal Return: Cosmos and History, Penguin Arkana, 1989

Jeffrey Gantz (trans.), The Mabinogion, Penguin Classics, 1984

Miranda J. Green, Exploring the World of the Druids, Thames & Hudson, 2005

Gerallt Gymro, Lewis Thorpe (trans.), Liber de Principis Instructione, url: http://www.britannia.com/history/docs/debarri.html , retrieved Feb 2014

Robert Graves, The White Goddess, Faber & Faber, 1968

Eric Hamp, Mabinogi and Archaism, Celtica 23, 1999

Sarah Higley (trans.), Preiddeu Annwfn: The Spoils of Annwn, The Camelot Project, 2007, url: http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/preiddeu-annwn , retrieved Jan 2014

Mary Jones, Jones Celtic Encyclopedia, entry for Uffern, url: http://www.maryjones.us/jce/uffern.html , retrieved Jan 2014

William F Skene (trans.), Song Before The Sons of Llyr, in Book of Taliesin in The Four Ancient Books of Wales, containing The Cymric Poems attributed to the Bards of The Sixth Century, url: http://www.celtic-twilight.com/camelot/skene/book_taliessin_xiv.htm , retrieved Jan 2014

Encyclopédie de l'Arbre Celtique, Abandinus, url: http://encyclopedie.arbre-celtique.com/abandinus-4310.htm , retrieved March 2014

The Roman Britain Organisation, Durovigutum, url: http://www.roman-britain.org/places/durovigutum.htm , retrieved July 2012

RSS Feed

RSS Feed