|

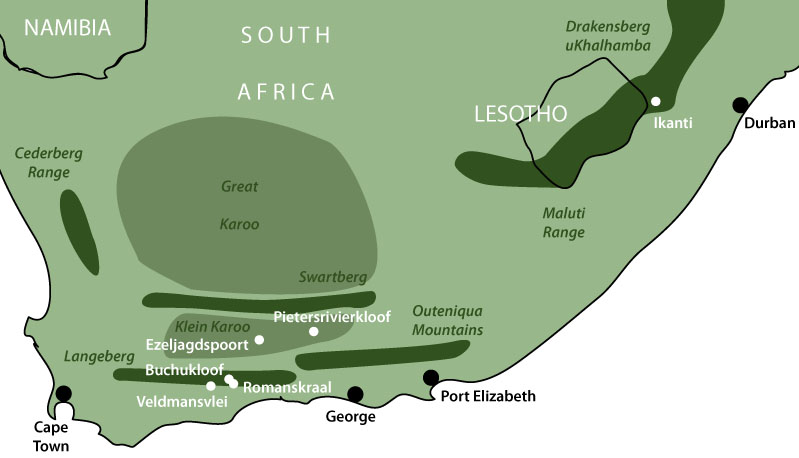

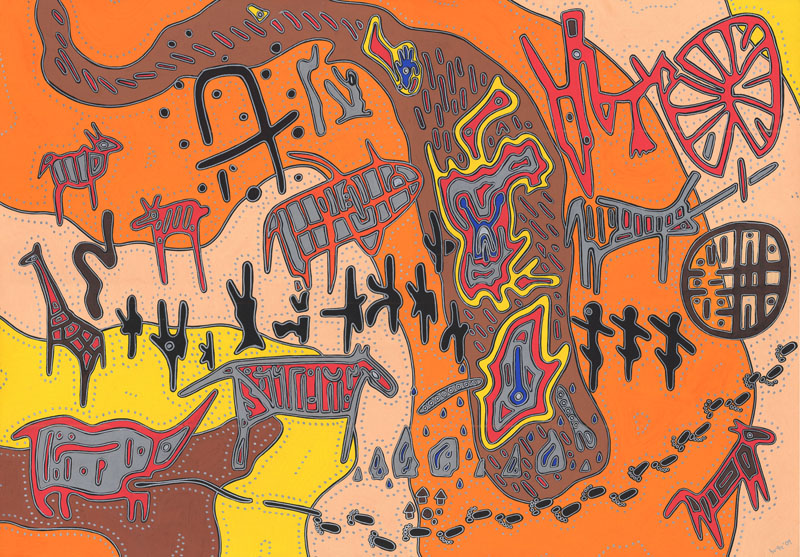

Let’s start as we mean to go on with the Archaic Visions reboot, and open the first strand with which this blog will continue – Rock Art of Southern Africa. Here I present rather a long article, the first in this series, which provides an introduction to Bushman Rock Art and Culture. It is rather academic in style in places, and the intention is to present to my readers a style of art and painting which shares next to nothing with familiar Western or Oriental art traditions in its method, approach, interconnection with religious and ritual practices, and even how it interacts with the environment in which it is found. If at times this series of articles seems to go into excessive detail, then this only reflects my genuine enthusiasm for Bushman rock art and engravings, and my deeply-held desire to understand, and to see these remarkable painted images through the eyes of the remarkable people who painted them. In this spirit, let’s begin this long, winding and hopefully fascinating journey into the world of the Southern African hunter-gatherer… Southern Africa is home to one of the most fascinating, and yet least well-known, art traditions in the world. Running in a near continuous line of rock shelters from the Cederberg in the West to the Drakensberg-uKhahlamba mountain range in the east, as well as across other sites in the subcontinent, the rock paintings and engravings of the indigenous hunter gatherer peoples of South Africa and beyond – the Bushman, San, or Khoi-San peoples and their cultural ancestors – represents one of humanity’s most distinctive art styles and, until its extinction some 150 to 200 years ago, one of the longest running.

5 Comments

For several years, one of my avenues of research has revolved around the Minoan civilisation of Bronze Age Crete, which has so far culminated in a treatise on the Minoan Epiphany as a visionary ritual. These researches are greatly enriched by visits I and my partner take to the archaeological sites and museums of Crete, and it was on such a journey in late 2013 when I had a flash of insight into how the perennial humanist concerns of Greek art may have had their formative moments. This essay, which is generally longer and more image-heavy than my usual Archaic Visions fare, is what followed. I have a vague plan to publish my Minoan Epiphany research in late 2016: this article is likely to form the introduction to that text. One of the major themes in the history of Aegean art, from its emergence out of the Greek Dark Ages at the end of the ninth century B.C. to its fullest flowerings in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, is appropriately summarised by Boardman, in the introduction of his comprehensive study on the subject, as:

“…its rapid but deliberate development from strict geometry admitting hardly any figure decoration, to full realism of anatomy and expression…” and its emergence into an authentic expression of what Perry has termed: “…the humanist spirit that characterized all aspects of Greek culture. They made the human form the focal point of attention and exalted the nobility, dignity, self-assurance and beauty of the human being.” The notion that the cave paintings of Southern France and Northern Spain during the Upper Palaeolithic were painted by shamans is so ubiquitous in the visionary community as well as other circles as to effectively have become a kind of dogma. In archaeology, however, in recent years, this idea has come to be challenged in favour of a more nuanced view, and many of the images previously thought as shamanic now partake in a wider understanding of what little we can know of the Palaeolithic cultural context, the function of the art itself and of human creative and ritual behaviours. In my many years of studies in Palaeolithic artforms, there seems to me now only a handful of images with unambiguously shamanic elements. One such painting might be the famous Bird Man of Lascaux, but as we shall see, despite the shamanic nature of this image, it is not exclusively so, and partakes of wider cultural forms as much as any other image...

In many ways, the often cited category of the ‘Palaeolithic cave painting’ is a clumsy term, not least because the phrase actually represents several widely divergent traditions visible in three discrete time periods (the early-to-mid Aurignacian, the Gravettian-Solutrean and the Magdalenian) stretching across nearly thirty thousand years of the European Upper Palaeolithic. As such, it is hardly likely that the same ritual functions and cultural imports of the paintings would have persisted unchanged for such a long time period – indeed important clues of these changes can be gleaned from the architectural spaces of the caves themselves and the siting of the art within them, as well as from the interactions between the cave sites, particularly in the latter two periods. There are also huge changes within the art itself, and the famous images of animals of the Eurasian Steppe represent only one strand of a rich set of traditions whose varieties and subtleties are easily missed from within a casual purview. In the earliest periods, dots and tectiforms of unknown meaning seem to predominate, but by the late Aurignacian (30-28kYa B.P.) the familiar images of bison, cave lions, deer and others take centre stage, with human-animal hybrids making occasional appearances. In the Magdalenian, abstract claviforms accompany animal images but the usage of the cave itself seems to be transformed into public and private spheres in a manner not seen previously. Palaeolithic Cave Art in Europe is celebrated as a profound expression of deft visionary and naturalistic skill. Once thought to have emerged fully-formed some 28,000 years ago, modern dating techniques and new discoveries are revealing the developmental processes of these artforms from simple dot and line compositions to the more skilfully-rendered friezes at Chauvet, Altamira, Lascaux and others, while at the same time showing that the majority of the art was created in three discrete periods, the early-to-mid Aurignacian (33-28 kYa B.P.), the mid-to-late Gravettian and early Solutrean (24-21 kYa B.P.) and the Magdalenian (18-12 kYa B.P.) with minimal surviving cave art activity between these times. The varied but simplistic art seen in El Castillo cave, Cantabria, Spain, generally belongs to the first two of these periods, but a recent uranium-series dating on one petroglyph dated it to almost 41,000 years, making it the oldest known cave art in Europe.

The Cave of El Castillo is one of several caves containing Palaeolithic art in the municipality of Puente Viesgo in Cantabria, Spain, situated some 20km southeast of the more famous cave at Altamira. Discovered in 1903 by Hermilio Alcalde de Río, the cave contains several chambers in which friezes of paintings are located, and there is evidence to suggest the cave was in intermittent usage from the Auriginacian until as late as the Bronze Age, and that during the Magdalenian may have formed, along with Altamira and other nearby caves, the core territory of a single human group. Indeed, there are several smaller Palaeolithic painted caves within the same mountain as El Castillo, and the area may have formed a key pilgrimage or sacred site for this group. In the Mexico Room of the British Museum, London, are three lintels (two originals, one archival cast) from the Classic Maya city of Yaxchilan in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. These exceptionally-crafted public artworks depict a fascinating ritual to evoke a Divine Ancestor, thus broadcasting both a sense of royal propaganda and of sacred intimacy, but it is the image of visionary beholding vision which is particularly interesting, disclosing an archaic expression to the scene. The Classic Maya city of Yaxchilan is one of several archaeological sites located in close proximity to the Usumacinta River along the border between Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas. It sits just on the Mexican side in a meander of the river, likely a vital spot since the river passed through the city and allowed the rulers to control – and perhaps impose duties upon – the trade and river traffic moving from the mountains towards lowland cities such as Palenque.

Anciently known as Pa' Chan ('Broken Sky') or Siyaj Chan ('Born from the Sky'), Yaxchilan's documented history begins around the mid 4th century AD but the city flourished in the Late Classic period (6th-9th centuries AD), dominating nearby Bonampak and the Usumacinta corridor, as well as establishing rivalries with both Piedras Negras and Palenque downstream. It seems reasonable, at the beginning of this Archaic Visions adventure, to recede back to a time when human symbolic culture was just dawning. Contrary to popular opinion, this was not the European Upper Palaeolithic: palaeoarchaeology has since the 1980s steadily been revealing a wealth of artefacts disclosing the emergence of symbolism, ritual and vision in Southern Africa in the Middle Palaeolithic. One such site is Tsodilo, a sacred locale in continuous usage for perhaps 24,000 years and possibly the site of the world's oldest known ritual. This essay has been adapted for an article originally written for a Ugandan arts magazine, and was more of a meditation on the age of the site than an in-depth study. In the northwest of Botswana’s Kalahari Desert, beyond the famous Okavango Delta, lies a small range of parched hills called Tsodilo, a UNESCO World Heritage site and perhaps one of the oldest sacred places in the world. For it is here, and in a few other sites dotted around Southern Africa, that we can come to know ourselves as human beings, through our shared origins in the soils of Africa.

On the far eastern coast of Crete, there lies in a remote bay the Minoan town of Zakros, a major Bronze Age urban centre. First discovered in 1902, the palace wasn't uncovered until the 1960s, and the artefacts from Zakros palace are some of the most celebrated works of art to emerge from the Minoan Civilisation. But during the original excavations at House A in the north of the town, a large number of clay sealings were unearthed, many of which bore the consistent hand of a single artist, a truly gifted seal-engraver with a profound and unique vision: the Zakro Master.

The Minoan civilisation is replete with sealstones. From the earliest Pre-Palatial periods in which the village chiefs marked their trade goods using simply-incised gems, to the late Proto- and Neopalatial periods in which complex iconographies were common for ruling families of the urban centres, Bronze Age Cretans made use of a range of religious and naturalistic imageries as part of their public identities. Seal-engravers drew upon a visual koine for their creations, a communal repository of mythological, naturalistic, religious and visionary forms that extended across most parts of the island. |

ARCHAIC VISIONS

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed