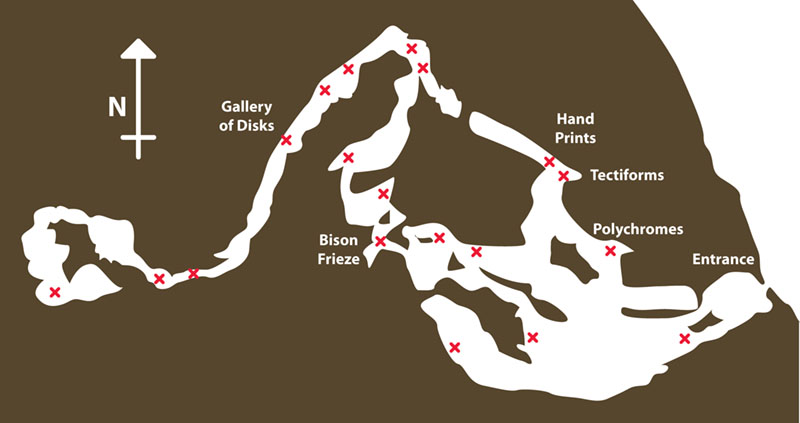

The Cave of El Castillo is one of several caves containing Palaeolithic art in the municipality of Puente Viesgo in Cantabria, Spain, situated some 20km southeast of the more famous cave at Altamira. Discovered in 1903 by Hermilio Alcalde de Río, the cave contains several chambers in which friezes of paintings are located, and there is evidence to suggest the cave was in intermittent usage from the Auriginacian until as late as the Bronze Age, and that during the Magdalenian may have formed, along with Altamira and other nearby caves, the core territory of a single human group. Indeed, there are several smaller Palaeolithic painted caves within the same mountain as El Castillo, and the area may have formed a key pilgrimage or sacred site for this group.

But the cave walls are also replete with hand prints, both in positive and negative forms, tectiforms of uncertain meaning and a prodigious number of dots which have been shown to be of a very great age indeed. It is these abstract images, whose interpretation has been the subject of lengthy and heated debate, that will be the main concern of the present essay.

“...some of the paintings were significantly older than suspected. Experts thought that Spanish cave art was younger than French cave art. But the new results reveal one of the images at El Castillo - a large red disk on the Panel de las Manos - is at minimum 40,800 years old... Other surprisingly old Spanish paintings identified in the study included a hand stencil from the Panel de las Manos that dates to at least 37,300 years ago and a club-shaped symbol from the famous Altamira cave that dates to 35,600 years ago...”

But at the same time, these tests open up a vast array of debates, particularly as to who the authors of these artforms really were:

“Anatomically modern humans arrived in western Europe around 41,500 years ago and thus may well have made the ancient Spanish paintings. But 42,000 years ago the only humans in Europe were Neanderthals... [Thus] any art there that turns out to be older than 42,000 years must necessarily be attributed to Neanderthals. [Pike & Zilhão] suspect that the red disks and hand stencils at El Castillo might well be Neanderthal paintings, considering that the uranium-thorium dating results are minimum estimates...”

This is startling stuff. Since the tests were conducted on the calcite overlay and not the paintings themselves, a date of 40,800 years BP for the red dot calcite implies the image itself is older and thus stands at an ambiguous point where Neanderthals and anatomically-modern homo sapiens were coexisting, or perhaps even before the latter had not yet arrived. Thus it is possible that the Neanderthals, previously not considered to have been capable of abstract thought or symbolic expression, may have been the authors of the earliest cave art in Europe.

Hand stencils in particular were made using very specific and difficult-to-master techniques, using black manganese pigments or red ochres in a watery consistency that facilitated their spraying and attachment to the wall surface. Experimental archaeologists, as reported by Paul Pettitt, have replicated the process using Palaeolithic technology – bivalve shells and bird-bones found underneath the hand friezes – and in so doing uncovered a fascinating dimension to these stencils:

“The experimental replication of hand stencils shows that they were best produced by blowing watered-down pigment of runny consistency through hollow tubes... A large bivalve shell was used to contain the runny paint, and a short tube inserted into it like a straw. Holding the ensemble close to the subject hand a second tube was used to blow across the first. This created a vacuum which sucked the pigment up from the shell and out as a fine spray.

Pettitt's team were able to show that in each cave, only a few individuals were involved in making hand-stencils and that they were often deliberately associated with cracks in the cave wall, leading to the suggestion that such cracks may have represented points at which there was a meeting of worlds. It has been asserted that in these earliest periods of occupation, the cave walls may have been perceived as a world beyond this world, and as such placing one's hand against and covering it with pigment – in effect, merging one's hand with the wall – constituted a form of contact with or even coalescence into that other world. The womblike, initiatory and Underworld archetypal attributes of caves across many human cultures may have found its first expression in this formative period.

“These compositions are intriguing and must have had a symbolic value that eludes us. Why were series of dots used to form lines? Do dots have their own particular significance, contributing and gaining meaning when combined in more complex geometric motifs?”

In both El Castillo and La Pasiega they are found away from the more public areas at the front of the cave, and while the 'Tectiform Recess' is a space big enough for three people to lay down, the height of the chamber and steeply reclining wall-to-ceiling surface precludes standing or walking: to enter one must shuffle along the floor in a fairly confined space. This is similar to Altamira, where a tectiform is found in a small crawl-space about as far from the entrance as it is possible to go. Such spaces lend themselves to interpretations of quiet contemplation, or private rituals by firelight, and in both El Castillo and Altamira, the tectiform friezes are associated with animal masks: large construal images of faces highlighted in the living rock.

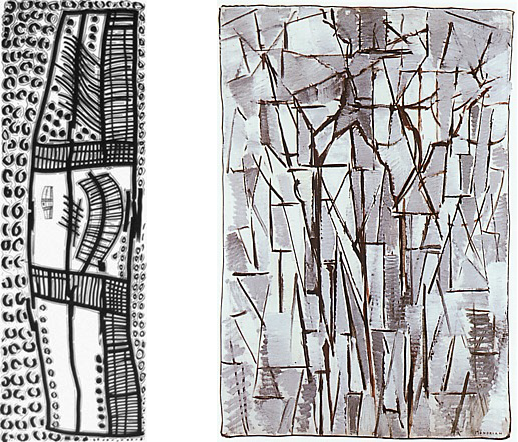

Cook summarises other ideas, including the notion that tectiforms connected by lines appear to denote some kind of religious meaning or social interaction between groups of dwellings, clans or locales. A calendric interpretation is also possible, since studies of portable art from the Czech Republic have demonstrated that some dot-and-line engravings on animal bones disclose evidence of a lunar notation. Harrod, on the other hand, considers the tectiform to be grapho-semantically similar to images of vulvas and other 'birthing' imageries: indeed we see several vulviform signs at El Castillo.

“The abstract figures... are not limited to only the hard-to-reach places or the most (or least) sacred. A possible explanation could be that the Palaeolithic people experienced trance and saw entoptic phenomena in the dark cave thanks to sensory deprivation of sight. In the absence of any stimuli, the brain creates images for us to see. It is likely these experiences were considered to be religious experiences, or contact with the spirits.”

The siting of many of the tectiforms at El Castillo in the aforementioned confined spaces might indeed suggest a visionary component here – it is difficult to imagine a public ritual in such a space – and the continual appearance of such geometric forms on portable art from the Middle Palaeolithic onwards in a variety of cultures from Southern Africa to Europe suggests a universality that may be entoptic in origin.

Lewis-Williams also considers entoptic phenomena to be the prime inspiration behind the these tectiforms, and the animal images to be an ecstatic or trancelike development of construal vision along what he terms an 'intensified' trajectory of consciousness which leads to hallucinations and visions as opposed to a 'normal' trajectory involved with dreaming and unconscious processes. He likens images such as the tectiforms to form constants whose origin is not within the eye or even the optic nerve, but as geometric visual phenomena emergent from the structure of the visual cortex itself.

In another work, Lewis-Williams and Dowson ascribe to the shaman the primary role of experiencing and interpreting these phenomena into artforms for wider dissemination, although he also notes among San rock art of the Drakensburg mountains in Southern Africa, the concerns of the painters (who tended towards iconicity) differed from those who made engraved images:

“The engravers seemed to have placed value and meaning on entoptic phenomena, but the painters seem to have been less concerned with them.”

Cook remarks, however, that entoptic phenomena may indeed be the subconscious inspiration behind such images as the tectiforms here, but cautions against a natural assumption that these necessarily represent shamanic or visionary images:

“Such primal patterns may be archetypal and ever-present because everyone experiences entoptic phenomena... Lewis-Williams and Dowson suggest that it is the role of the shaman to bring them into view as symbols through heightening the experience of such visions when in an ecstatic state such as trance. This is a circular argument necessitated by an underlying belief that some patterns are symbols that represent ideas and must involve the pre-frontal cortex of the brain but originate as sensory perceptions in another part of the brain. This is unsatisfactory... because it denies the possibility that any individual might make the neural links between the different areas of the brain that contribute the basis of creativity.”

In other words, Cook rejects Lewis-Williams' and Dowson's thesis on the grounds that it is too robotic, and implies that entoptic phenomena originating in the visual cortex proceed with minimal attenuation directly to the brain's pre-frontal cortex for re-cognition as symbol, an automatic process that inadequately encapsulates the flexible neurological realities of the human creative mind. She also uses the examples of work by artists such as Piet Mondrian, whose artforms seem entoptic, but actually represent attempts to convey visual perceptions of the movements of trees and water through...

“...abstract patterns of short lines, meanders, grids and concentric semicircles...which may resemble entoptic phenomena but were conceived not to express the working of the subconscious brain but to explore and offer metaphors for external objects in different ways... In this respect, art makes things visible, not the shaman...”

'Composition Trees II', Piet Mondiran, 1912

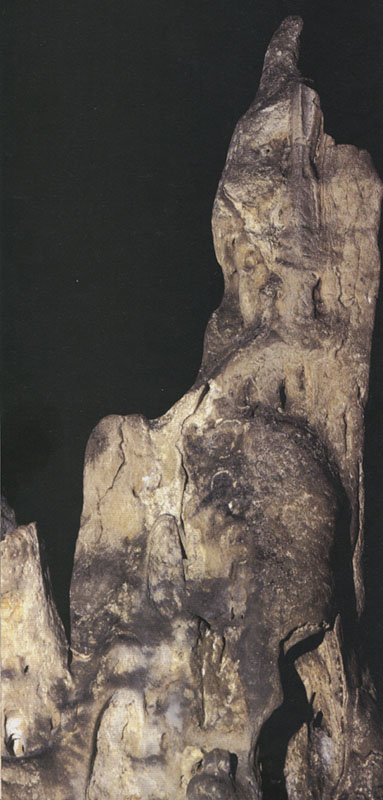

Such, then, are the abstract images at El Castillo. But aside from the polychrome animal paintings and more formative monochrome images, the cave has one more sight to offer, a human-animal hybrid from the Magdalenian, the last period of Palaeolithic occupation. The El Castillo Bison Man is located in one of the intermediate chambers between the Main Chamber and the Gallery of Disks. Clottes narrates:

“In one of El Castillo's main chambers, an ancient stalagmitic mass occupies a central position. It is all the more spectacular as its top ends in the shape of a bison horn. The natural curve of its irregular surface was incorporated into the drawing of a bison, which is oriented vertically and to the left. The animal's back extends into a long tail as it follows the natural relief of the mass. Eduard Ripoll... studied the image and discovered a firmly engraved human leg, showing that this was in fact a composite creature, both human and animal... The upright posture stresses the human aspect of the mysterious creature...”

This enigmatic image of possibly shamanic or clan-totem intent will be explored and contextualised in a future essay entitled 'Human-Animal Hybrids in the European Upper Palaeolithic', but for now we can view it as perhaps the final beautiful expression of a Palaeolithic reality at El Castillo, one which developed across some twenty-five millennia from the earliest dot-like abstractions and otherwordly hand stencils to a recognisably figurative image of what, if mythology from contemporary hunter-gatherers is any guide, must have been a sacred image indeed.

Jill Cook, Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind, The British Museum Press, 2013

James B. Harrod, Deciphering Upper Paleolithic (European): Part 1. The Basic Graphematics – Summary of Discovery Procedures, Language Origins Society, 1998, edited 2004

Don Hitchcock, El Castillo Cave, in Don's Maps: Resources for the study of Palaeolithic / Paleolithic European, Russian and Australian Archaeology, url: http://donsmaps.com/castillo.html , retrieved September 2007

Eva Hopman, Hallucinogens and Rock Art: Altered states of consciousness in the Palaeolithic period, University of Gröningen Institute of Archaeology, 2008, url: http://www.academia.edu/1397021/Hallucinogens_and_Rock_Art_Altered_States_of_Consciousness_in_the_Palaeolithic_Period , retrieved April 2014

David Lewis-WIlliams, The Mind In The Cave, Thames & Hudson, 2002

J.D. Lewis-Williams & T.A. Dowson, The Signs Of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art, Current Anthropology, Vol. 29 (2), 1988

Paul Pettitt, Hand Stencils in Upper Palaeolithic Cave Art, Durham University Department of Archaeology Research Project Report, url: https://www.dur.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/?mode=project&id=640 , retrieved April 2014

Pedro A. Saura Ramos (ed.), The Cave Of Altamira, Harry N. Abrams, 1998

Texnai Digital Archive, Paleolithic Cave Arts in Northern Spain(1) El Castillo Cave, Cantabria (1998), url: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t0j9NC1hID0 , retrieved April 2013

University of Bristol Press Release, El Castillo Cave (Espagne): Paleolithic paintings date back at least 40,800 years, url: http://www.archeolog-home.com/pages/content/el-castillo-cave-espagne-paleolithic-paintings-date-back-at-least-40-800-years.html , retrieved April 2014

Kate Wong, Oldest Cave Paintings May Be Creations of Neandertals, Not Modern Humans, Scientific American, June 2012, url: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2012/06/14/oldest-cave-paintings-may-be-creations-of-neandertals-not-modern-humans/ , retrieved April 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed