The Minoan civilisation is replete with sealstones. From the earliest Pre-Palatial periods in which the village chiefs marked their trade goods using simply-incised gems, to the late Proto- and Neopalatial periods in which complex iconographies were common for ruling families of the urban centres, Bronze Age Cretans made use of a range of religious and naturalistic imageries as part of their public identities. Seal-engravers drew upon a visual koine for their creations, a communal repository of mythological, naturalistic, religious and visionary forms that extended across most parts of the island.

The Zakro Master appears to have lived in or near the palace at Zakros, engraving seals for the ruling families of the palace as well as for the merchants and traders at Zakros - Weingarten employs a complex but ingenious line of logic to suggest that his clients were mostly women, and posits that he lived around 1500BC, some two generations before the destruction of the town. It is likely he did not live long enough to witness this destruction.

Even by the bizarre standards of Eastern Crete, the Zakro Master's work stands out: starting from the local tradition of chthonic and animal-hybrid images, he developed personal and fantastical responses to these themes, often merging previously-disparate imageries to create novel and innovative forms.

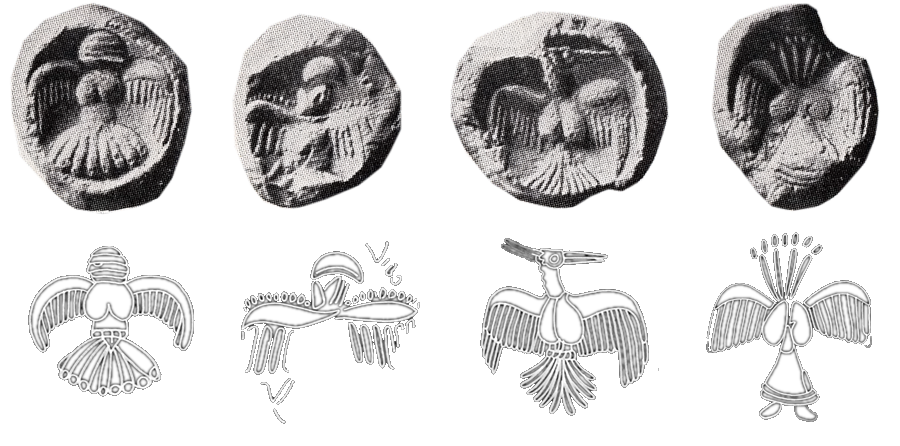

Large-breasted Bird Ladies (designed to be seen in the impression rather than the original engravings) blend into fantasy animal masks, bucrania (bull-heads) meld into gorgons and Minotaurs, the like of which is seen nowhere else, either in Crete or in the wider Bronze Age Mediterranean. Judging from the surviving body of his work, it is not unreasonable to suggest that the Zakro Master is one of the earliest individuals (rather than anonymous collective) whose work can be identified as forming an essential link of the evolving lineage of the visionary, the imaginal and the fantastic.

Intriguingly, some of the earliest depictions of human-bull hybrids are seen in the Zakro Master's work; generally images of the Minotaur are held to be a later Greek invention, but it is possible that the imagination of this visionary engraver from the Bronze Age palace at Zakros was the seed of this now well-known archetype.

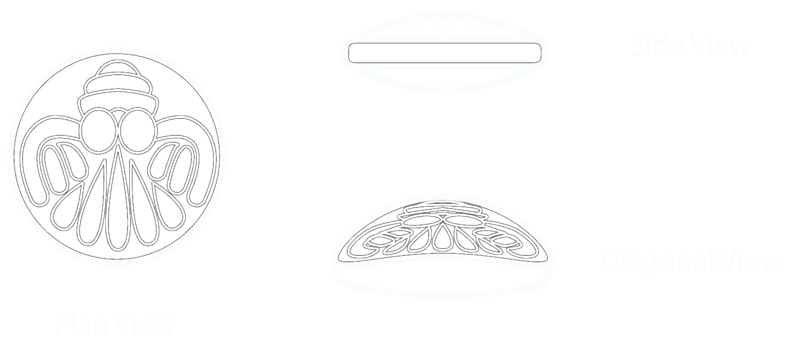

Many figures greet the viewer face-on in a posture consistent with vertical symmetry, but in cases where the head is turned sideways, such symmetry-breaking is often compensated for with balancing features, such as a head-dress, horns or antlers. The lentoid form was thus for him a framing device rather than an absolute boundary: far from being a limitation, the small circular area was here transformed into an advantage.

Typically for an archaic visionary, the Zakro Master's work has since its discovery undergone a number of conflicting assessments, largely influenced by the dominant ideologies of the day. In the early part of the twentieth century, Evans and Della Seta confined themselves to utilitarian analyses and limited criticisms, while deeper misgivings were voiced by Nilsson, who dismissed the images as the product of an "overactive, fever-stricken imagination". Gill preferred the Zakro Master to be "a madman, encouraged by the townsfolk in the belief that the sealstones from his hand would have had an extra touch of the supernatural". Thus do we see the rationalist influences of the mid 20th century on the assessments of the Zakro Master's work.

It wasn't until 1970 that the art historian John Boardman began to rehabilitate the Zakro Master: "The Zakro impressions are work of rare ability and imagination. The devices are grotesques composed of human and animal parts with which Hieronymous Bosch could well have felt at home...The Zakro Master created an idiom which goes far beyond anything we can find again in the history of Minoan or indeed Greek art. The technique is perfect."

Here, then, we see genuine appreciation of the sealstones not merely as Minoan artefacts, or as religious symbols, but as artistic visions springing from the mind of a talented individual. Simandiraki-Grimshaw further added to the praise: "…[his] reinvention and combination of hybrid elements ranges from innovation and whim to psychedelia."

Describing him as an artist who drew from the corpus of Minoan chthonic deities, albeit often developing them beyond recognition, she has identified a number of signs of the Zakro Master's hand, outlining his strong sense of symmetry, his expression of contrast between light and shadow in the depth of the engravings, his delight in women of generous proportions bearing accessories such as belts or necklaces, and the subject's lack of torsion, a feature so ubiquitous elsewhere in Minoan art. Using such criteria, she has reconstructed a possible stylistic history of the Zakro Master, suggesting possible orders in which the sealings may have been created.

From the surviving evidence, he appears to have begun his career engraving fantasy animal mask designs such as lions and boars that have a certain antecedent in eastern Cretan engraving traditions. But his originality is evident even in these early works: boar masks contain winged elements, horns transmute into human legs, and lion eyes could equally be embryonic breasts which evolved later into Bird Ladies. His stylistic development continues in the exploration – and to a certain extent deconstruction – of the form of the Bird Lady image, transforming her into side-facing leaping forms and running winged forms. The final works posited by Weingarten are the bucrania in which for the first time we see irregularity and asymmetry in the Zakro Master's oeuvre.

What, then, of the Zakro Master's legacy? His influence does appear to have been fairly limited in his own lifetime, whether because of the provincial nature of his sphere of influence or perhaps because of his unreachable individuality, nonetheless a few engravers at Zakros, Sklavokampo and at Ayia Triada show some of his influence in their works. Later, the rising prestige and aesthetics of Knossos in the years up to 1400BC had no time for eastern eccentricities and the destruction of many Minoan sites after this period sent many of Crete's most talented engravers abroad to find work in the Mycenaean courts on the Greek mainland, environments which often did not tolerate or understand the uniqueness of Cretan art, let alone the chthonic oddities and animal hybrids of Zakros.

Alessandro Della Seta, Religion and Art: A Study in the Evolution of Sculpture, Painting and Architecture, London, 1914

David George Hogarth, The Zakro Sealings, in Excavations at Zakro, Crete, British School of Athens, 1902

Martin P. Nilsson, The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion, Biblo & Tannen, 1950

Anna Simandiraki-Grimshaw, Minoan Human-Animal Hybridity, in The Master of Animals in Old World Iconography (Derek B. Counts & Bettina Arnold, eds), Archaeolingua Alapitvany Budapest, 2010

Judith Weingarten, The Zakro Master and his place in prehistory, Paul Åström Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Göteborg, 1983

Judith Weingarten, Aspects of Tradition and Innovation in the work of the Zakro Master, in Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, Supplément 11 pp167-180, Persee, 1985

Judith Weingarten, The Zakro Master and Questions of Gender, Aegeum 30, 2009

RSS Feed

RSS Feed