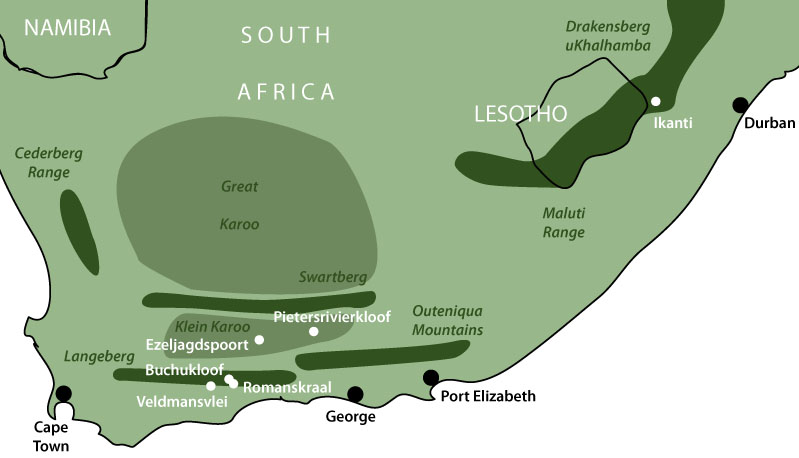

Rock art sites are found throughout Southern Africa, but they are particularly concentrated in the aforementioned line which starts in the Cederberg in the Western Cape, continues through the Langeberg and Outeniqua mountain ranges in the Southern Cape, as well as in the Klein Karoo just to the north of these, eastward to the Maluti range in Lesotho, and then into the Drakensberg-uKhahlamba mountains (Vinnicombe, 1976) where some of the most spectacular artworks are preserved. Other areas of intensely concentrated paintings can be found in the Brandberg Massif in Namibia (Fliegel Jezernicky Expeditions, 2010), the Tsodilo Hills in Botswana (Rimell, 2014a) and the Matopo Hills in southwestern Zimbabwe (Garlake, 1995; Parry, 2000), as well as Mashonaland in northern Zimbabwe (Garlake, 1995) and the Limpopo province of South Africa.

Further inland are other sites, such as in the Great Karoo of the Northern Cape where a large number of geometric and abstract rock engravings are to be found (Dowson, 1992), and the Limpopo Basin where Bushman paintings are associated by later Bantu-speaking peoples with a kind of spiritual ‘capture’ of prey animals (Eastwood & Eastwood, 2006). Dowson (1992, pp5-7) notes that the engravings tend to disclose a different subject matter to the paintings: the former tend to have a stronger entoptic and geometric character than the paintings, which focus more on naturalistic depictions, although not exclusively.

(Dowson, 1992, p56)

(Parkington, 2008, p25)

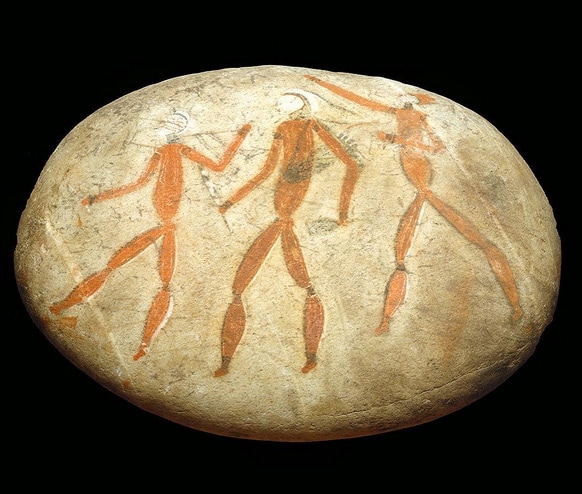

Mazel reports (2009a, pp81-97) that dating techniques have greatly improved since the 1970s, and gives a series of radiocarbon dates (p90) for encrusted organic deposits overlaying several paintings in the Drakensberg of between 1000 and 2900 years old. Parry notes (2000, pp9-13) meanwhile that Bushman peoples disappeared from Zimbabwe some 2000 years ago, which sets a minimum age for the rock art in the Matopo Hills, and she suggests (2000, p13) from stylistic evidence that rock art in the region may stretch back to 13,000 years ago. The finding of the Coldstream Stone in deposits dating to 9000 years ago (British Museum, 2016) also supports this ancient date for the painting traditions.

“…an attempt, however imperfect, at a truly artistic conception of the ideas which most deeply moved the Bushman mind, and filled it with religious feelings.” (Lewis-Williams, 2004, p55)

Bleek also spoke of Bushman paintings disclosing a “higher character” (Lewis-Williams & Dowson, 1989, p29) beyond mere idle daubings or art for art’s sake. However in a colonial age where licences were still being granted by South African authorities to hunt and kill Bushman peoples as if they were animals, his was a lone voice of reason.

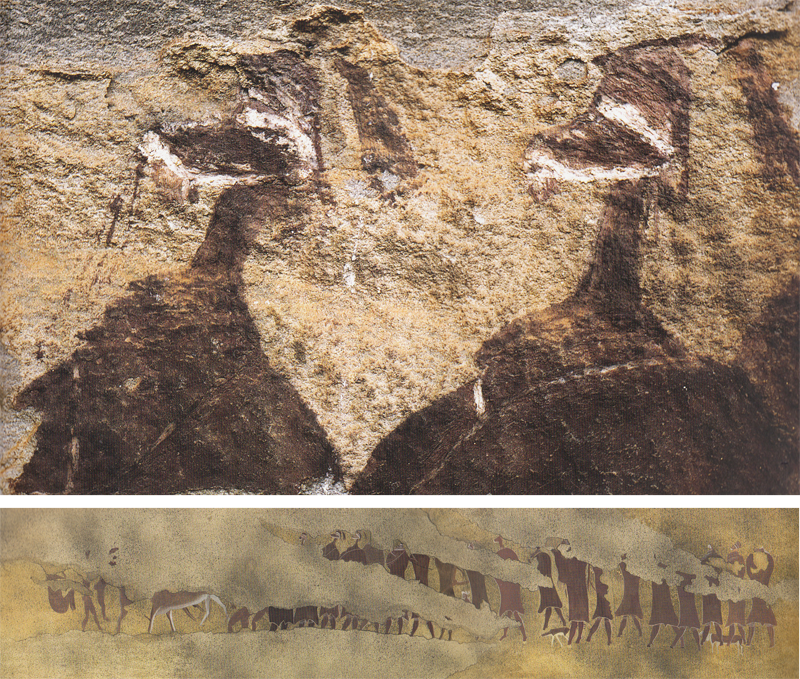

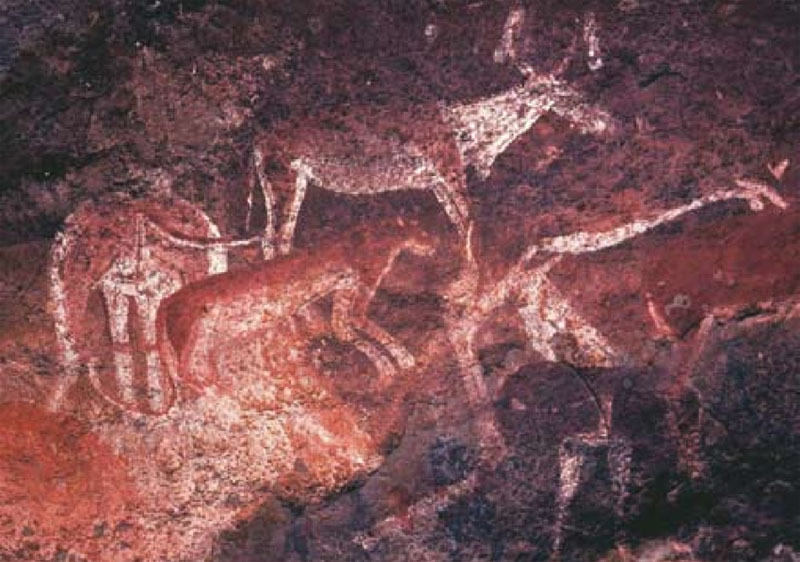

Makhenckeng, Qacha’s Nek District, Maluti Range, Lesotho

(Vinnicombe, 1976, p301)

His florid prose describing his encounter with this figure, however, hides the implicit assumption that only with some prehistoric arrival of a white person was the Bushman suddenly capable of ‘Great Art’. His fanciful and Eurocentric beliefs also blinded him as to the true nature of this image, which a closer examination reveals to be male as Lewis-Williams narrates:

“Had he [Breuil] been a bit more careful, he would have seen that the figure has a penis. Moreover, the penis is ‘infibulated’, that is, it has a short line drawn at right angle across it, and to, make the questions that this overlooked detail raises even more interesting, the line is fringed with small white dots. These dots suggest that the infibulation is associated with another feature of San rock art… a sinuous bifurcating red line, similarly fringed with white dots… Breuil’s ‘charming young girl’ is certainly male and has no features to distinguish it from other elaborately detailed San rock art images.” (Lewis-Williams, 2004, p5)

fissure and rising up towards a scar in the rock, where they disappear (Romanskraal, Langeberg,

Western Cape) and ii) Seven to ten faded white clay figures in shamanic postures emerging from

a 1cm inequality in the rock face (Pietersrivierkloof, Uniondale District, Western Cape)

This idea of using the rock features suggests a profoundly different approach to composition, and this difference is compounded by another common feature of Bushman rock art, overpainting and superposition of images (Lewis-Williams, 2004, pp29-48). At many rock art sites, images are crowded onto a single panel in a particular locale, despite the presence of other relatively flat walls nearby which in principle could have been used for art but were not. Instead, later figures are painted over earlier figures, and sometimes the surface of the rock is smeared with red ochre before painting the later images.

Pietersrivierkloof, Uniondale District, Western Cape

In subsequent articles, we will begin to see why certain sites were chosen in the first place, since the environment in which they were located seem to already disclose some magical, potent or otherworldly property which likely invoked the attention of the Bushman artists. The site may have commanded excellent views over the surrounding countryside, or was located next to a waterfall and pond whose water was dark in colour due to the presence of a natural mineral. Alternatively, a supernatural potent animal, such as the bee or a swift, may have had its nest very close to the site of the paintings, or the rock art was located at the top of a kloof, or ravine cut by a small stream, a challenging terrain up through which it was necessary to climb in order to arrive at the site. The Bushman artists seemed to have nearly always chosen their sites in this way: in particular, sites in the Klein Karoo seem to have been oriented closely towards the presence of water.

i) & ii) Cederberg, Western Cape, iii) Veldmansvlei, Langeberg, Western Cape,

iv) Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

David Lewis-Williams in particular transformed the nature of the research field by seeking to develop three separate strands of epistemology (see Lewis-Williams, 1995; also 2004, pp133-161) regarding Bushman rock art, and the prehistoric religion and society of the artists who created the images. These are: i) the rock art itself, closely studied, recorded and reproduced along with its archaeological, geological and environmental context, ii) nineteenth century /Xam ethnography from the archive of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd, which contains very many important cultural details not always understood at the time, along with twentieth century ethnography of Kalahari Bushman peoples such as the !Kung, and iii) the neuropsychological model of altered states of consciousness, in which objective psychological studies of the effects of altered states and visionary experiences are applied to study of the rock art imagery.

when seen through shamanic, ethnographic and neuropsychological perspectives

i) Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal, and ii) Ezeljagdspoort, Klein Karoo, Western Cape

Lewis-Williams reports (2004, p255-57) that the ritual of paint-making in which eland blood is used implies that a group of Bushman people would need to hunt before any painting could take place. Hunting is enfolded into a whole array of social attitudes and religious beliefs in all Bushman cultures, and none more so than the hunting of the eland, which is both the largest antelope and the most supernaturally potent in Bushman conception. This hunt would set off a sequence of ritual associations relating to this supernatural potency.

of the eland at lower left. Ikanti, Southern Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

“A young girl would accompany the eland hunting party and [she]… 'hypnotised' the eland. She did this by pointing an arrow, which had 'medicine' on it prepared by the medicine men, at the eland. The eland would become dazed and semi-paralysed. It would be led back to the hunters to the cave under their supernatural control. Here it became dizzy and would slip and fall. It would be killed by having its throat cut.” (Jolly, 1986, p6)

The informant further described how the eland would murmur and tremble when near death, and emit foam from its nose. After it died, cuts would be made on the eland’s forehead, neck and rib cage to extract blood, which was mixed with fat to make medicine. Some of this mixture was also mixed with paint (1986, p7)

Game Pass Shelter, Kamberg Nature Reserve, Southern Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

Thus, the process of making paint for rock art was not merely an isolated occasion in Bushman thought, but a ritually potent event deeply embedded within a complex of other, equally emotive and supernaturally powerful events, including: i) the eland hunt itself; ii) the young girl’s magical hypnotising of the eland; iii) its dizziness and apparent trance along with its death throes apparently mirroring the behaviours of the shamans in trance; iv) the staging of a Great Dance after the hunt in which ritual potency was amplified, and these dances may have been held at rock art sites such as Romanskraal and Ezeljagdspoort where large flat areas suitable for dancing are seen; and v) the making of paint from the eland’s blood and fat, mixed with powdered red ochre, which itself may have been a supernaturally potent substance judging by the ritual nature in which it was handled and prepared

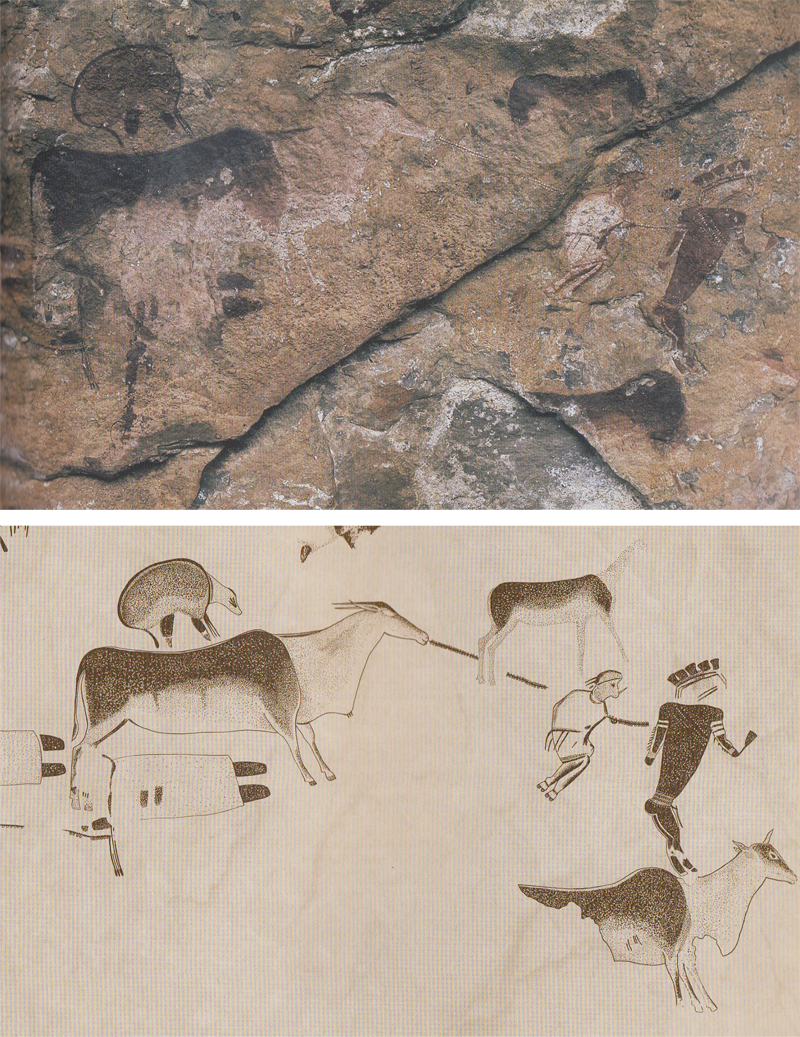

ii) the fragmentary panel from which this detail is taken (painted tracing by Patricia Vinnicombe)

Veryan Farm, Umtai River, Southern Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

(Vinnicombe, 1967, pp316-17)

Both Vinnicombe (1967, pp131-33) and Mazel (2009a, p94) elucidate the various styles seen and attempt to decipher them into a roughly chronological sequence for the Drakensberg paintings, as follows:

Phase I paintings are, as Vinnicombe describes (p131) “mostly very fragmentary and little can be deduced as to their content and style.” They are mostly monochrome in dark reds and maroons. Mazel notes that some antelope and human figures conform to this style and the paint is effectively stained into the rock face.

Phase II paintings consist of human figures and animals in bichrome red and white colours, and sometimes polychrome with varying shades of red with white, and with some shading visible between the tones. Black is sometimes introduced for human figures, and the white tones are sometimes only evident due to bleaching on the rock face, the original paint having faded.

Esikolweni Shelter, Cathedral Peak Nature Reserve, Central Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

(Mazel, 2009a, p88)

Botha’s Shelter, Cathedral Peak Nature Reserve, Central Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

(Mazel, 2009b, p95)

The majority of rock art sites I have visited have tended to evidence the last three of these phases, and particularly Phases III and IV. At Ikanti, I saw both polychrome images in shaded browns and white, as well as monochrome red ochre friezes. At Pietersrivierkloof in the Outeniqua mountains, a dazzling array of styles was seen, all superimposed on one another, including polychrome shaded browns and white, bichrome red and yellows, monochrome red ochre, monochrome white, and bichrome white and black. Monochrome red ochre of various tones including reds, oranges and purples and monochrome yellow ochre images were seen at Veldmansvlei, as were bichrome red and overpainted yellow

Game Pass Shelter, Kamberg Nature Reserve, Southern Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

Parkington narrates (2008, pp38-42) that red ochres could come in several different tones from orange to purple and were made principally from “weathered oxides or hydroxides of haematite and limonite.” (2008, pp39-40) Iron-rich shales were also sometimes used to achieve a bright pinkish tone. Black tones, meanwhile, appear to have been made from powdered manganese dioxide and white was made from clays which is often fragile and easily damaged or faded. It is not clear exactly what the binding medium would have been in all cases: despite the ritual narration above, it is unlikely that eland blood was used for every single painting, and Parkington suggests (2008, p41) that egg white, plant saps, blood and fat may have been used, or a mixture of these. He also notes that the fine lines and adhesive quality of the paint generally rules out water alone as a medium.

(Rust & van der Poll, 2011, p43)

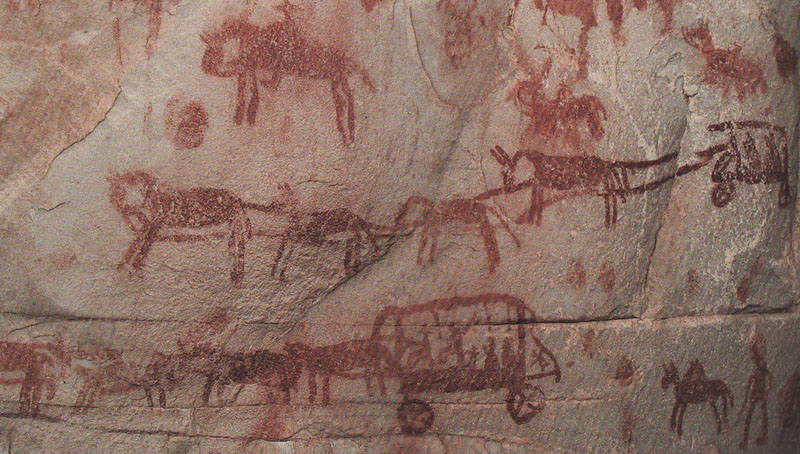

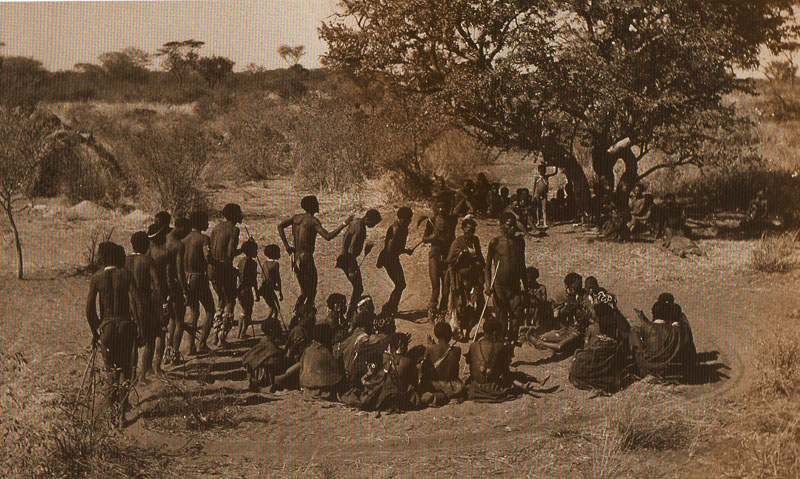

Predominant in the religious life of the Bushman was the Great Dance (Bannister & Lewis-Williams, 1998, pp74-75), a healing trance dance officiated by shamans who fell into altered states of consciousness (Lewis-Williams & Challis, 2011, pp51-72), and very often felt themselves transformed into animals or as passing into the world of spirits to effect their healing methods. Dances such as these are still performed by Kalahari Bushman peoples such as the Ju’/hoansi (Keeney & Keeney, 2015), and the same bending-over postures, linked arms and gestures such as pulling the arms sharply backwards which are seen in Ju’/hoansi dances are also seen in the rock art (Lewis-Williams, 2004, pp63-64; Lewis-Williams & Challis, 2011, p101).

Note the circular formation and track on the ground with singing and clapping women in the centre

(Vinnicombe, 1976, p305)

In addition to depictions of the Great Dance, rituals relating to the rain and weather control are also commonly seen. Perhaps the most ubiquitous is the killing of a ‘rain’ animal (Vinnicombe, 1967, pp314-344; Lewis-Williams & Challis, 2011, pp110-31), a visionary event in which one or more ‘rain sorcerors’ (in the words of nineteenth century /Xam informant /Hanǂkasso; Lewis-Williams & Challis, 2011, p99), or shamans of the rain, entered the world of the spirits to capture an eland, elephant or other supernaturally potent creature, and then ‘kill’ it and lead it across the sky, its blood falling as rain to replenish the land so that the people could feed themselves. There is a finely-rendered, although faint and partially obscured, representation of this ritual at Pietersrivierkloof, which we will see in a forthcoming article. Some images which were previously considered to be hunting scenes may well depict this event.

Predictably, the animals which Bushman peoples believed to be the most supernaturally potent are the ones which are most commonly depicted. The eland, the bearer of !gi par excellence (Lewis-Williams & Challis, 2011, p57), is the most commonly seen, as is the elephant which was also a supernaturally potent animal (Lewis-Williams, 2004, p114) in the conception of Bushman peoples. Surprisingly, depictions of /Kaggen, the Mantis, the principal shaman trickster figure in /Xam mythology, appear to be quite rare, however, since /Kaggen was also held to transform himself into many other guises (Vinnicombe, 1967, p158), so it is possible he is present as other, non-insectoid, animal figures and has therefore not been often identified. He is also closely associated with the eland in myths and spiritual conception, as the Maluti Bushman Qing explained in the 1870s:

“We don’t know [where /Kaggen is] but the elands do. Have you not hunted and heard his cry, when the elands suddenly start and run to his call? Where he is, elands are in droves like cattle.” (Vinnicombe, 1976, p170)

the polychrome eland is being led by a chord through its nose by two shamans with eland hooves

Anteater Shelter, Tsoelike, Qacha’s Nek District, Maluti Range, Lesotho

(Vinnicombe, 1976, p163 & p327)

There are also plenty of images which do not pertain to the shamanic or to supernaturally potent animals or dances, for example, those pertaining to menstrual rites. At Willcox’s Shelter and Sorceror’s Rock in the Drakensberg are two images (Vinnicombe, 1967, pp152-53) which seem to evoke androgynous, therianthropic and menstrual associations (Knight, Power & Watts, 1995, p94) while at Fulton’s Rock, there may be seen a depiction of the Eland Bull Dance, a rite for new menstruants (van der Post & Taylor, 1985, pp60-61 & Plate 44). Fight scenes, such as the image called ‘Veg ‘n Vlug’ (‘fight or flight’) in the Cederberg (Parkington, 2008, pp64-65) and processions (Vinnicombe, 1967, p109) like that seen at Ikanti in the Drakensberg are also sometimes found.

Fulton’s Rock, Highmoor Wilderness Area, Central Drakensberg, Kwazulu-Natal

The entrance into an altered state and the constant depiction of this experience in the rock art is one of ten aspects of shamanism that Lewis-Williams lists (2004, p196) and contrary to Bednarik's words (in 2013, p493), it is more than mere performance. Rather the practice reflects a pervasive experience in Bushman culture specifically and human culture more generally, whether it is termed shamanism or not, and it is the various aspects of this experience (rather than its nomenclature), along with the cultural institutions with which it was intimately associated, that are expressed in the rock art. Furthermore, as Lewis-Williams says, the shamanic interpretation is

“… not a final, monolithic ‘explanation’ of San rock art. Rather, it opens up to limitless possibilities for new and ever more detailed insights into the iconography and… into San mythology, cosmology and social relations.” (2004, p95)

(Parkington, 2008, p64)

However, preceding the site visit articles in many cases will be some short articles about generic features of Bushman rock art which are intended to ‘prepare’ the reader for the imagery seen in the subsequent site visit article. So for example at Ikanti Site #1, a frieze of painted polychrome elands is seen, along with a fragmentary depiction of what may be a rain-making ritual, and so preceding this site visit will be two articles exploring eland paintings and rain-making in Bushman art and culture. Hopefully, this approach will make the detailed descriptions and photographs of the site visit articles a more immersive and enriching experience for the reader!

*2 – Fascinatingly, Vinnicombe reports (1967, p158) a number of different orthographic and dialectal variations on the name of the Bushman trickster-shaman deity, /Kaggen, the Mantis. These include Kaggen, Cagn, ctaggen, and most strikingly Qhang. It is possible therefore that the name of this red ochre pigment may have resonated with the name of the deity in the Maluti Bushman language, although this is a speculation based upon admittedly slender evidence

Bednarik, Robert (2013), Myths About Rock Art, Journal of Literature and Art Studies 3 (8)

Breuil, Henri (1948), The White Lady of Brandberg, South-West Africa, Her Companions and Her Guards, South African Archaeological Bulletin 3 (9)

British Museum (2016), ‘South Africa: The Art of a Nation’ 27 October 2016 – 26 February 2017, on The British Museum, dated October 2016, url: http://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_on/exhibitions/south_africa.aspx, retrieved May 2016

Deacon, Janette (1994), Some views on Rock Paintings in the Cederberg, Department of Environment Affairs South Africa / Cape Nature Conservation / National Monuments Council of South Africa

Dowson, Thomas (1992), Rock Engravings of Southern Africa, Witwatersrand University Press

Eastwood, Ed & Cathelijne Eastwood (2006), Capturing the Spoor Rock Art of Limpopo: An Exploration of the Rock Art of Northern Most South Africa, David Philip Publishers

Fliegel Jezernicky Expeditions (2010), Upper Brandberg Expedition, Namibia, 21th June - 4th July, 2010, on FJ Expeditions, url: http://www.fjexpeditions.com/frameset/namibia10.htm, retrieved April 2017

Garlake, Peter (1995), The Hunter's Vision: The Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe, University of Washington Press

Hitchcock, Robert K. & Megan Biesele (2014), San Khwe, Basarwa or Bushmen? Terminology, Identity and Empowerment in Southern Africa, on Khoisan Peoples, url: http://www.khoisanpeoples.org/indepth/ind-identity.htm, retrieved November 2014

How, Marion Walsham (1962), The Mountain Bushmen of Basutoland, J. L. Van Schaik Ltd

Jolly, Pieter (1986), A First Generation Descendant of the Transkei San, South African Archaeological Bulletin 41 (143)

Keeney, Bradford & Hillary Keeney (eds.) (2015), Way of the Bushman as Told by the Tribal Elders: Spiritual Teachings and Practices of the Kalahari Ju/’hoansi, Bear & Company

Knight, Chris, Camilla Power & Ian Watts (1995), The Human Symbolic Revolution: A Darwinian Account, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 5

Lewis-Williams, David (1972), Superpositioning in a Sample of Rock-Paintings from the Barkly East District, South African Archaeological Bulletin 29

Lewis-Williams, David (1980), Ethnography and Iconography: Aspects of Southern San Thought and Art, Man (N.S.) 15

Lewis-Williams, David (1995), Seeing and Construing: The making and ‘Meaning’ of a Southern African Rock Art Motif, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 5 (1)

Lewis-Williams, David (2004), A Cosmos in Stone: Interpreting Religion and Society through Rock Art, Altamira Press

Lewis-Williams, David & Thomas Dowson (1989), Images of Power: Understanding Bushman Rock Art, Southern Book Publishers

Lewis-Williams, David & Thomas Dowson (1990), Through the Veil, San Rock Paintings and the Rock Face, South African Archaeological Bulletin 45

Lewis-Williams, David & Sam Challis (2011), Deciphering Ancient Minds: The Mystery of San Bushman Rock Art, Thames & Hudson

Mazel, Aron D. (2009a), Images in Time: Advances in the dating of Maloti-Drakensberg Rock Art since the 1970s, in Peter Mitchell & Benjamin Smith (eds.), The Eland’s People: New Perspectives in the Rock Art of the Maloti-Drakensberg Bushmen – Essays in Memory of Patricia Vinnicombe, Witwatersrand University Press

Mazel, Aron D. (2009b), Unsettled times: Shaded polychrome paintings and hunter-gatherer history in the southeastern mountains of southern Africa, Southern African Humanities 21 (1)

Oudtshoorn Courant (2015), Help Preserve our Rock Art, on Oudtshoorn Courant, dated May 2015, url: http://www.oudtshoorncourant.com/news/News/General/136148/Help-preserve-our-rock-art, retrieved May 2017

Parkington, John (2008), Cederberg Rock Paintings: Follow the San, Creda Communications & Clanwilliam Living Landscape project

Parry, Elspeth (2000), Legacy on the Rocks: The Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the Matopo Hills, Zimbabwe, Oxbow Books

Rimell, Bruce (2014a), Tsodilo: The Beginnings of a Human World, on Archaic Visions, dated April 2014, url: http://www.visionaryartexhibition.com/archaic-visions/tsodilo-the-beginnings-of-a-human-world, retrieved April 2014

Rimell, Bruce (2014b), The Migraine as Archaic Visionary Experience, on Archaic Visions, dated August 2014, url: http://www.visionaryartexhibition.com/archaic-visions/the-migraine-as-archaic-visionary-experience, retrieved August 2014

Rust, Renée & Jan van der Poll (2011), Water Stone & Legend: Rock Art of the Klein Karoo, Struik / Random House

van der Post, Laurens & Jane Taylor (1985), Testament to the Bushmen, Penguin

Vinnicombe, Patricia (1976), The People of the Eland: Rock Paintings of the Drakensberg Bushmen as a Reflection of their Life and Thought, Witwatersrand University Pres

RSS Feed

RSS Feed