“…its rapid but deliberate development from strict geometry admitting hardly any figure decoration, to full realism of anatomy and expression…”

and its emergence into an authentic expression of what Perry has termed:

“…the humanist spirit that characterized all aspects of Greek culture. They made the human form the focal point of attention and exalted the nobility, dignity, self-assurance and beauty of the human being.”

This perennial image of Greek art – a fusion of Oriental elements with native Greek genius – is backed by a considerable array of evidence, perhaps the best known of which are the Egyptian kouros and Daedalic style under Syrian influence, and their importation into Classical imagery. However, the influence of Aegean cultures from before the Dark Ages, and in particular the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisations, are often overlooked in this view. There is ample evidence that cultural survivals endured past the collapse at the end of the Bronze Age in several ways – particularly in Crete, the islands and in backwater locales such as Arcadia – among which include tendencies towards law codes which expressed a certain level of political egalitarianism, matrifocal religious practices and an attraction towards naturalistic and pastoral scenes in art.

These traits are exemplified particularly by the Minoan civilisation, the non-Greek culture centred upon Crete and the Cyclades, and remarkably it is here, rather than upon the mainland, that the first glimmerings of the later recurrent humanist concerns can be seen.

The Minoan civilisation of the early-to-mid Bronze Age of Crete represents in some ways a fascinating counterpoint to the general themes of contemporary Eastern Mediterranean cultures. In Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the Levant, primary artistic expressions concerned the hieratic relationships between humans and gods, the duties of the king towards his people, and expressions of that king’s strength, through the valorisation of warfare and smiting of enemies, or his legitimacy, through his intimacy with the gods and his adherence to ritual. Sacred and royal figures are often muscular, larger-than-life and of an iconicity which seems designed to engender awe and exaltation.

i) Ring of Minos (detail), Knossos, c.1450-1400 B.C.

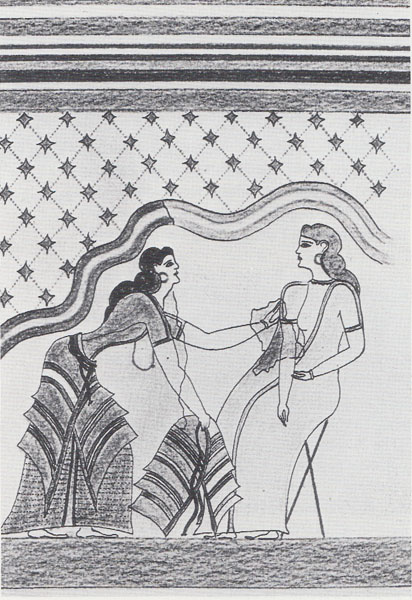

ii) Reconstruction of Dancers Fresco, Knossos, c. 1450 B.C.

iii) Bronze figurine of saluting man, Tylissos c.1550-1450 B.C.

iv) Assyrian Lion Hunt, Palace of Ashurbanipal, Nineveh, c. 650 B.C.

v) Nebamun hunting in the marshes, Thebes, Egypt, c.1350 B.C.

“Art in Bronze Age Crete… is characterized by a fortunate combination of stylization and spontaneity, abstraction and true ‘impressionistic’ naturalism, quite different in spirit from its contemporaries in the Near East. The Minoan artist… reacts with flexibility and creative power, managing to transform everything into a personal creation, an artistic world of his own. From the beginnings this art, although ruled by conventions, avoids stiff forms and dullness of any kind, often transcends anatomical realism and instead is fond of movement, fluidity, colour, dynamism and vitality… Minoan art is delicate, sophisticated and joyful throughout its evolution.”

Kerényi characterised Minoan art as “the art of life”, stating that he intended specifically the Greek word ζοη here, referring to vitality and the natural, energetic principle of life, and quoted Platon’s summary of the Minoans as:

“…a civilization whose characteristics were the love of life and nature, and an art strongly imbued with charm and elegance. Their objects of art were miniatures, worked with care and love… They had a special inclination towards the picturesque and to painting, and even their miniature plastic work is elaborated in styles derived from painting… the figures move with lovely grace, the decorative designs whirl and turn, and even the architectural composition is allied to the incessant movement becoming multiform and complex.”

There is nothing of the Near Eastern hieratic or the awe-inspiringly powerful here: as Platon notes, the scale of Minoan art is often intensely personal, favouring seal images and portable figurines as sacred images rather than grandiose icons. Only in the palace frescoes do we see larger-than-life images, but here, the depictions seem to be mostly of rituals, dances and scenes of nature rather than deities or kings as we would expect from other Eastern Mediterranean cultures. Minoans also seem to have been as preoccupied with the beauty of youth as the Greeks, but with a focus upon movement rather than perfection, while expressions of the sacred tended to depict intimacy and visual equality between deity and human rather than awe or difference, depictions which radically transform our understanding of how these people engaged with their gods.

An example of this intimacy is beautifully evidenced in the Poros ring, from a tomb near Heraklion, dating to around 1450 B.C., in which is seen a ‘sacred conversation’ between a human celebrant and deity. This ring forms part of the corpus of images which form the Minoan Epiphany, a ritual practice which appears to have had as its primary intent the seeking of a direct vision of a deity who alights from the sky and makes contact with the earth before the visionary celebrant. The gold ring is considerably worn, making the interpretation somewhat challenging, and the action depicted is both complex and ambiguous. The first aspect we may note is the dynamism and torsion of the male figure at the right, whose ecstatic ‘tree-pulling’ action appears to authorise the visionary nature of the scene.

“The goddess as a small hovering image in the scene descending from the sky… shows the intermediary action… which recalls a previous episode happened before the main action scene on the ring. This multilevel [sic] narration process is finally dramatized by the arrival and landing of the goddess seated on a shrine which is not positioned on ground level…”

The female deity at the left, still apparently floating and flanked by two ornately-rendered birds, is thus likely to be the same as the floating figure, and we see here a disclosure of narrative action in the goddess descending out of the sky in the upper centre to reach ground level. Her arm is partially outstretched to meet the outstretched arm of the male figure, and it is by this mirroring of arm postures that the 'sacred conversation' is suggested and the expression of intimacy is disclosed.

The Poros ring typifies the aforementioned visual equality between deity and celebrant: they are depicted on the same level and of a similar size, but an ambiguity emerges when we realise that the male’s posture closely matches other epiphany images in which the figure, sometimes male and sometimes female, is definitely a deity and often depicted floating. The Goddess alighting from the sky in the context of a religious ritual is common enough in Minoan art that we might be able to speculate that Minoans believed the deity came readily to attend the ritual, and the ecstatic ‘tree-pulling’ seen on the Poros ring and several others was incipient to the vision. This is a profoundly different relationship to the sacred than one we in the modern West are accustomed to!

This apparent lack of icons and the hieratic can perhaps be seen as a little strange: the Minoans were expert craftspeople and thus perfectly capable in theory of creating large-scale statuary, and so this absence begins to seem like a cultural choice. Despite their considerable talent with ceramics, stonework and stone relief, relatively little evidence of the kinds of hieratic iconicity seen elsewhere has come to light. For a society which appeared to greatly value ritual and religious depictions, this needs an explanation, and begs the question: where, if anywhere, is the hieratic to be found in Minoan art?

The central male figure on the Poros ring, with characteristics of both deity and ritual celebrant, becomes relevant to our theme here, since this ambiguity is a ubiquitous feature of many Minoan images of religious practice. Indeed it recalls the Greek idea of the human body as a perfect vessel for the divine, and perhaps indicates an interesting direction for an answer, in the notion of the ‘enacted epiphany’.

Hägg was the first to realise that Minoan depictions of the epiphany could be classified into two types, one based on a visionary experience (as seen above in the Poros ring), and a second one, in which according to Galanakis:

“…worshippers carrying offerings approach a seated deity whose role may have been acted by a high priestess impersonating the divinity.”

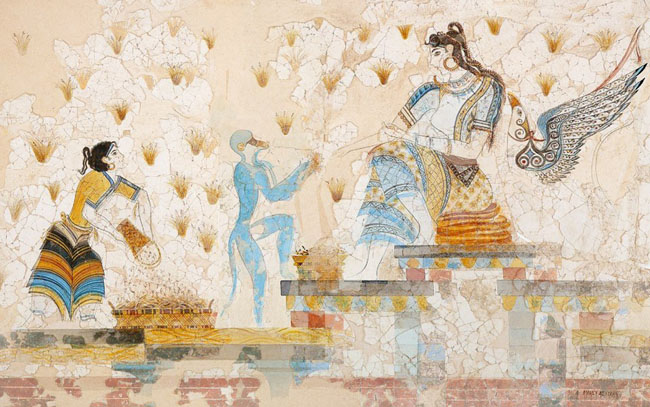

“At left we see a woman offering saffron to an enthroned female figure, with other sacred elements present, the monkey and the griffin. The life-sized nature of the figure at right suggests in part that this she represents a surrogate for the deity, enacting her role in a ritual of offering.”

and, like the Poros ring, there is to a certain extent an expression of visual equality between deity (whether enacted or not) and worshipper or celebrant, although upon later reflection I began to consider the seated figure in the Xeste 3 fresco to be somewhat larger-than-life when compared to the woman making an offering at the left.

Warren also notes another fresco from Akrotiri, in the House of the Ladies, in which a robe is being offered to a female figure whose form is fragmentary and poorly-preserved. The offering woman bends forward to gaze at what may be a similarly ‘enacted epiphany’ as above:

“She [the enacted epiphany] appears to have been seated, but a standing position is not impossible, since the woman stooping to place the skirt is also looking upwards… Nanno Marinatos, in her perceptive discussion, takes the recipient figure to be a priestess being clothed for a ceremony… [and that] she might well be a representation of a goddess, seated or standing, or… a goddess in the person of a priestess.”

It should be noted in this regard that despite the human-sized, and possibly larger-than-life, images in these depictions, no large statues, wooden or otherwise, have been found at Akrotiri, despite the excellent preservation of what is popularly called the Aegean Pompeii. This is an important indicator that Hägg’s idea, this humanised deity impersonation, has more than a modicum of veracity.

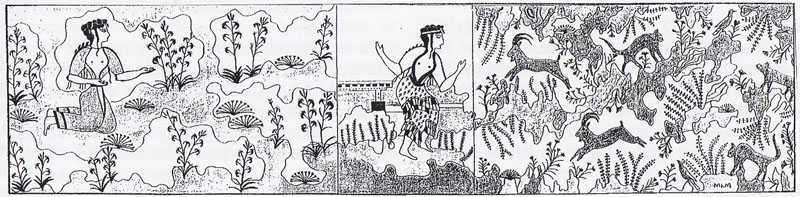

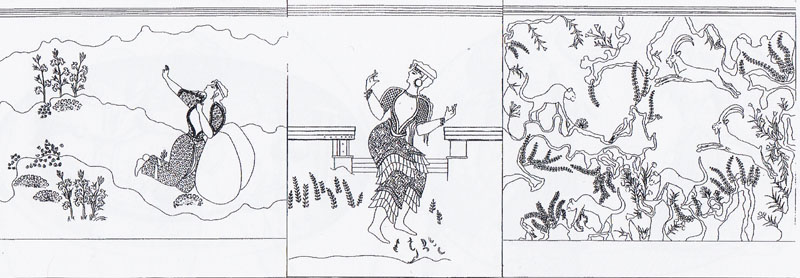

In her survey of Minoan religion, Moss describes a reconstructed fresco at Ayia Triada which provides a different possible context for the ‘enacted epiphany’ phenomenon, in that it contains a depiction of at least two women, both of which bear epiphanic attributes. This three-panel scene was heavily destroyed by fire and is thus fragmentary, as she narrates:

“Of the left-hand panel… all that remains is the lower part of the figure from half-way down her thighs and some of the landscape; in the central panel… we have some part of the woman from the waist downwards and some of the building; about two-thirds of the third panel which appears to show cats, birds and agrimia frolicking in a rocky landscape is missing…”

“Her arms are raised away from her body, and the pronounced bend of her hips and knees (along with the suggested movement of the skirt) suggests that she is… dancing. On the fresco, the woman stands in front of a structure that may be described as a seat…”

and quotes Rehak in stating that:

“…the pose and placement of the… [central] female make it reasonable to designate her a goddess, presiding over her natural realm, rather than a human being or priestess.”

In this light, it is perhaps natural to consider the dancing female to be an epiphany of the goddess appearing to the kneeling woman, but this interpretation is challenged by the observation that the left-hand woman is depicted at larger-than-life size, and this communicates with the two frescos from Akrotiri. Thus it is relevant to question whether the kneeling woman is not the goddess, or an ‘enacted epiphany’ who in the Minoan cultural reality is identified wholly with the goddess, while the central dancer is in fact an ecstatic figure similar to the ‘tree-pulling’ male on the Poros ring. Moss notes the ambiguity here:

“So, do we have two goddesses, or two representations of one deity? It is impossible to tell…”

Elsewhere in depictions of the Minoan Epiphany we see similar situations, in which the presence of a living ‘enacted epiphany’ appears to guarantee the arrival of the goddess in visionary epiphanic form (such as on the Isopata Ring where the rightmost woman appears to be an elder woman depicted at a slightly larger size to the other figures in the scene) and it is perhaps useful to assume that while both women represent deities of some kind in the Minoan conception, the question of which one is the human and which one is the ‘actual’ deity (in our Western conception) remains closed to us.

“The tallest figure… wears a tall tiara with a spotted snake coiled around it, a necklace, a tight-waisted short-sleeved bodice richly embroidered, with a laced corsage, leaving the large white breasts bare, and a long skirt with a kind of short double apron over it. The hair falls down behind on the shoulders. Her eyes are black. Her arms are stretched out in front of her. The snake’s tail interlaces with another snake which coils around her body and with its head appearing at her girdle. She holds a third snake which coils over her shoulder.”

Meanwhile, the smaller and more well-known figure, is:

“…similarly dressed, but her skirt is flounced. She has a slim waist and bare prominent breasts. Her arms are extended and she grasps a snake in each hand.”

A striking but little-seen aspect of the smaller figurine is its dynamism, which is often lost in frontal photographs of the artefact, and is best seen from the side. Her back is arched, her body is tense and alert, and there is the suggestion of some kind of altered stated of consciousness (of which, more below) in the depiction of her eyes as wide and staring. That she is also in motion is apparent from the lines of her skirt, which are not symmetrically arranged: rather the skirt lends the impression that one unseen foot has been placed forward with the other foot back, features which are expertly rendered through the shape and flow of the flounced layers, and lending an impression similar to postures seen in ‘saluting’ figurines from peak sanctuaries in central Crete. This movement lends a human touch to the depiction, and partakes of the same delightful characteristics of torsion, movement and naturalism that are the hallmarks of Minoan art.

Again we find ourselves in a social reality where the distinction between the icon of a deity and the depiction of a living woman ‘acting’ or ‘being’ the deity appears to have little relevance. Both ideas seem to have partaken in a seamless symbolic and perceptual experience in which a sense of the living hieratic and emerging humanist were fused into one.

This is precisely the kind of ‘enacted epiphany’ we have been discussing, and we might speculate that in the Minoan conception, it was a living deity, rather than a ‘priestess’ who was venerated and envisioned here. Goodison investigated the solar alignments of this area of the palace, noting that the ante-room and throne room both face east towards the dawn light whose passage into the throne room space was facilitated by transom windows above the doorways. The interaction of these architectural features with the sunlight and the gently sloping hill of Prophitis Elias to the east of the site was observed and photographed by Goodison and she concluded that the throne room was most effectively illuminated at midwinter dawn, as she narrates:

“It was only looking afterwards at photographs taken on the first midwinter dawn investigation that we noticed that the dawn light entering at that time of year through the southernmost doorway… passes through into the “Throne Room” itself, on a line… to illuminate the stone ‘throne’ and whoever may have been seated on it... This alignment resonates with [the] suggestion, based on the iconography of the adjoining wall-paintings… that this seat may have been the site where epiphany of the goddess was enacted… The possibility afforded by the architecture and orientation of closing off the entire pier-and-door colonnade onto the courtyard and then opening only the S[outh] door at the moment of sunrise to illuminate the “throne” might have provided [an] element of surprise and impact.”

There are important implications for this practice of sacred performance, some of which have been highlighted by Morris & Peatfield, whose work in the Minoan context has tended to criticise ‘representational’ interpretations of Minoan ritual practice in favour of an embodied perspective in which a deeper view is taken of the human body as an actor of considerable agency in ritual behaviours. Here, actions are not simply performative, but take on internalised characteristics:

“Even the most superficial actor is aware… of the emotional power of drama, that what you do affects how you feel. The drama is not simple pretence, but a collective participation... This is the 'internal' dimension of action: physical action can be used to affect emotional and psychological states, and to access altered states of consciousness, which transcend everyday realities.”

Elsewhere, they note that expressive, energetic and dramatic ritual actions engender a susceptibility to begin to envision or otherwise sense the presence of the deity. In their words, “the body is the conduit to experiencing the divine…” and they note that many of the stereotypical postures and gestures seen in ritual depictions throughout Minoan art appear to bear a tension that may have visionary or shamanic potentials. Experiments with such gestures by McGowan under controlled conditions have indeed liberated altered states of consciousness and visionary experiences, demonstrating that such gestures were meaningful to Minoan celebrants beyond the representational and offering significant challenges to what Morris & Peatfield have called the “rather passive ritual behaviour” of modern Western religion.

We are also witness to a religious situation which profoundly blurs the lines between customary Western notions of actor versus role, celebrant and deity, and between the one who sees and that which is seen. We find ourselves in a realm where, in the strict but perceptual language of ritual, an actor does not simply enact, but rather becomes the deity whom she performs, in her own mind as well as the minds of all the other celebrants. Thus the ‘enacted epiphany’ is itself a visionary experience of sorts, and envisages the deity in human form, dancing and interacting with the other participants through exemplary actions that only a deity could make.

It is here, in the gestures and performative drama of the living deity, that the hieratic in Minoan art may rather paradoxically be found – static large scale sculpture replaced by a dynamic human form – and this, at length, is how a concern for the humanist could steadily arise in the focus of Minoan ritual upon the beauty, dignity, expressiveness and sanctity of this curiously liminal and ambiguous conception of the human body.

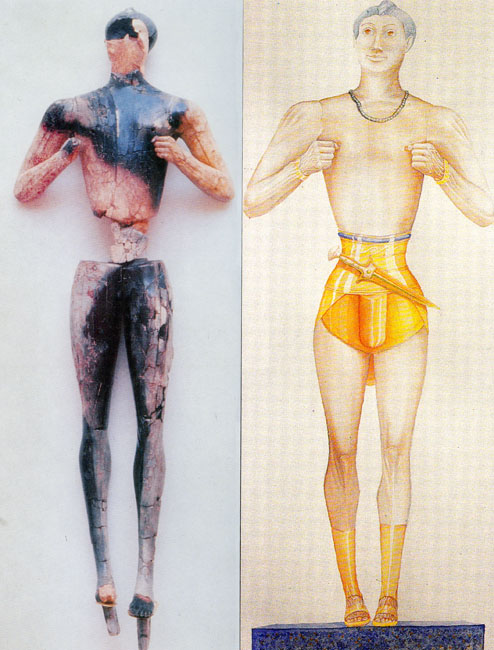

Perhaps the clearest example of this emerging humanism in Minoan art can be seen in the Palaikastro Kouros, a fragmentary figurine which perhaps communicates most clearly with the later Greek ideals of beauty, and of the human as divine figure. Found at the site of House 5 in the town of Palaikastro in eastern Crete, it was evident that this chryselephantine (hippopotamus ivory) sculpture had anciently been destroyed in what appears to have been a conscious act of vandalism, and as such the face has not survived. However, enough of the arms, hands, legs and feet endured for a fairly accurate reconstruction to be posited.

What is remarkable about this figurine, however, especially in light of later Greek developments is the level of anatomical accuracy demonstrated, as Sackett notes:

“Several details of the human anatomy represented on this figure… include the chest muscles… perhaps the shoulder… the arm muscles above and below the elbow and the muscles, tendons and veins of the forearm and hand, where the accuracy could be compared with that of a modern textbook. Details of wrist… hands… fingers and fingernails are impressive in their attention to detail. Leg muscles, too, are represented with accuracy, as are the neatly carved toenails and veins, carefully rendered…”

before concluding that in its depiction of youthful beauty:

“…the artist was interested in a careful and detailed expression of the human anatomy. His creation was to be as fine as an anthropomorphic form can be.”

It is impossible to know from the surviving evidence and iconography whether a similar style of ‘enacted epiphany’ obtained for this ‘Young Male Hunter’ deity at Palaikastro as it did for the aforementioned goddess at Knossos and Akrotiri – although here we must recall the central male figure on the Poros ring and say that perhaps there was – but in this figurine we can see perhaps the most refined expression of how the humanist was ambiguously born from the living hieratic figure of a youthful model. Furthermore, the attestation of a Zeus Kouros cult at Palaikastro in the Classical Greek era indicates that at least in one locale, such native Aegean proto-humanist concerns may have communicated their survival even through the Dark Age and Archaic periods into the re-flowering of Greek culture some one thousand years after the fall of the Minoan civilisation.

Thus we see in the practices and concerns of Minoan religion, in the careful attention to anatomical details and a love of physical vitality, bodily movement and dynamism in Minoan art which was so keenly felt and so intensely appreciated that it almost completely replaced the perennial attachment to large-scale hieratic sculpture that was the common hallmark of Near Eastern culture. We see then the birth of the humanist in Minoan art, through an archaic conception of the human body not merely as vessel for an externalised divine, but as a hieratic divine agent, and perhaps even as a generator and owner of that divinity. As an important mediator between the sacred and the mundane world, this liminal humanism prefigured the later and more realised human/divine conceptions of the Classical Greek world, and planted a fascinating cultural seed from which we in the modern West are still reaping the fruits of profound inspiration.

John Boardman, Greek Art, Thames & Hudson, 1964

Sam Crooks, What Are The Queer Stones? Baetyls: Epistemology of a Minoan Fetish, Archaeopress British Archaeological Reports, BAR International Series 2511, 2013

Costis Davaras, Guide to Cretan Antiquities, Eptalofos S.A. & Noyes Press, 1976

Jan Driessen, The Court Compounds of Minoan Crete: Royal Palaces or Ceremonial Centers?, Athena Review: Journal of Archaeology, History and Exploration 3 (3): 57–61, 2003, url: http://www.athenapub.com/11court.htm, retrieved September 2012

Konstantinos Galanakis, Minoan Glyptic: Typology, Deposits and Iconography – From the Early Minoan period to the Late Minoan IB destruction on Crete, Archaeopress British Archaeological Reports, BAR International Series 1442, 2005

Lucy Goodison, From Tholos Tomb to Throne Room: Perceptions of the Sun in Minoan Ritual, in Laffineur, R. and Hägg, R. (eds.), Potnia. Deities and Religion in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 8th International Aegean Conference. Göteborg, Göteborg University, 12-15 April 2000. Aegaeum 22. pp. 237-243, University de Liege/University of Texas, 2001

Robin Hägg, Epiphany in Minoan Ritual, in Mycenaean Seminar, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 30 (1), 184-185

Karl Kerényi, Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, Mythos: The Princeton/Bollingen Series in Mythology, Princeton University Press, 1976

Evangelos Kyriakidis, Aniconicity in Late Minoan I Seal Iconography, Kadmos, 43 (1). pp. 159-166, 2004

Alexander MacGillivray & Hugh Sackett, The Palaikastro Kouros: The Cretan God as a Young Man, in J.A. MacGillivray, J.M Driessen & L.H. Sackett (eds.), The Palaikastro Kouros: A Minoan Chryselephantine Statuette and its Aegean Bronze Age Context, British School at Athens Studies 6, 2000

Erin Ruth McGowan, Experiencing and experimenting with embodied archaeology: Re-embodying the sacred gestures of Neopalatial Minoan Crete, in Archaeological Review from Cambridge: Issue 21.6: Embodied Identities, pp32-57, University of Cambridge, 2006

Marina L. Moss, The Minoan Pantheon: Towards an Understanding of its Nature and Extent, Archaeopress British Archaeological Reports, BAR International Series 1343, 2005

Christine Morris & Alan Peatfield, Feeling Through The Body: Gesture in Cretan Bronze Age Religion, in Yannis Hamilakis, Mark Pluciennik, Sarah Tarlow (eds.), Thinking Through The Body: Archaeologies of Corporeality, Springer, 2001

Christine Morris & Alan Peatfield, Experiencing Ritual: Shamanic elements in Minoan Religion, in Michael Wedde (ed.), Celebrations: Sanctuaries and the Vestiges of Cult Activity: Selected papers and discussions from the Tenth Anniversary Symposium of the Norwegian Institute at Athens, 12-16 May 1999, University of Bergen, 2004

Jonathan Musgrave, The Anatomy of a Minoan Masterpiece, in J.A. MacGillivray, J.M Driessen & L.H. Sackett (eds.), The Palaikastro Kouros: A Minoan Chryselephantine Statuette and its Aegean Bronze Age Context, British School at Athens Studies 6, 2000

Martin P. Nilsson, The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion, Biblo & Tannen, 1950

Marvin Perry, Western Civilization: A Brief History, Vol 1: To 1789 (Eleventh Edition), Cengage Learning, 2015

Bruce Rimell, Postures of the Epiphany Dance, unpublished notes, 2009

Bruce Rimell, The Minoan Epiphany: A Bronze Age Visionary Culture – Archaeological Evidence for Visionary Ritual and Altered States of Consciousness in Cretan Prehistory, personal essay, url: www.biroz.net/words/minoan-epiphany/, dated March 2013

L.H. Sackett, The Palaikastro Kouros: A Masterpiece of Minoan Sculpture in Ivory and Gold, Hellenic Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund Publication, 2006

Warren, Peter, Minoan Religion As Ritual Action, Gothenburg University & Eric Lindgrens Boktryckeri A.B., 1988

RSS Feed

RSS Feed