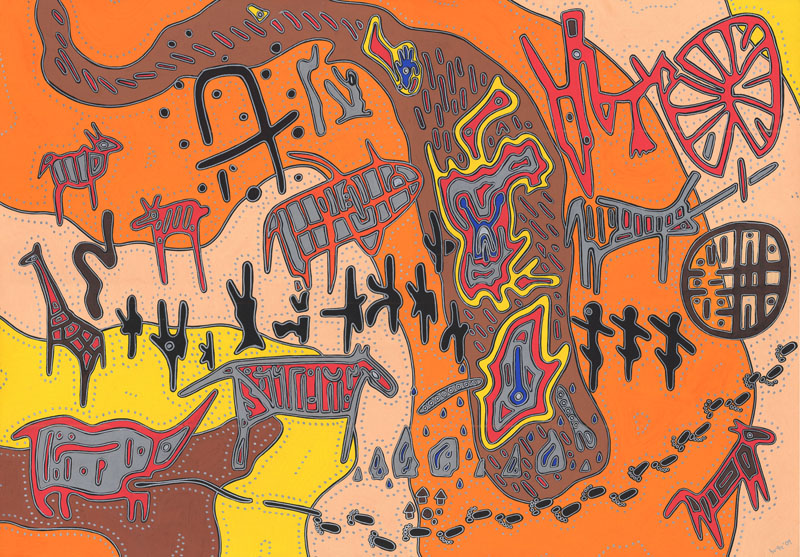

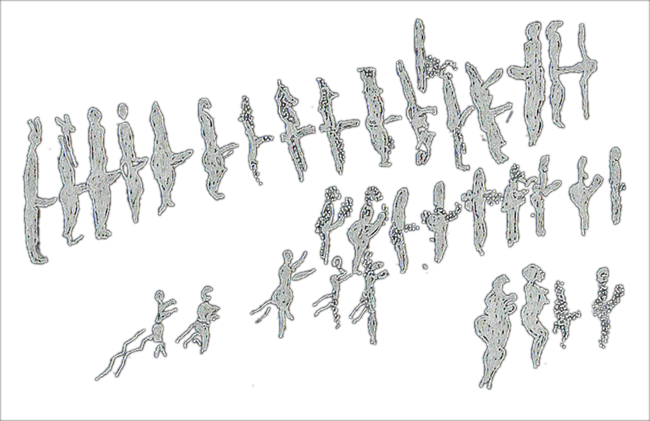

The Female and Male hills are covered with rock art in a variety of styles and a variety of motifs: familiar images of giraffes, rhinos, zebras and even fish give us important clues about what the ancient painters of these artworks held to be important. In such an unforgiving environment as the Kalahari Desert, the animals who offered themselves up as food to the hunter gatherer peoples were the beings most worthy to be reproduced upon the rocks.

Their interpretation is perenially unclear: academic debate tends towards various interpretations from notable chieftains or shamans to ancestral hunters now in the afterlife. Given that the current San living around Tsodilo believe that the hills contain the spirits of their dead, this latter notion seems more tempting, although Coulson and Campbell consider these friezes to represent unknown ceremonies. At a place like Tsodilo that speaks so eloquently of our ancient human experiences and yet equally remains so silent, there will always be questions unanswered.

In 1995, two exciting discoveries were made by archaeologist Sheila Coulson and her team: upon the Male hill there was found a giant sculpture of a python carved out of the living rock, positioned almost as if it should command reverence, and sculpted in such a way that it would be an awe-inspiring sight by day or night. Coulson herself said of the six metre long python: "You could see the mouth and eyes of the snake. It looked like a real python. The play of sunlight over the indentations gave them the appearance of snake skin. At night, firelight gave one the feeling that the snake was actually moving."

(No high resolution image of this important artefact could be found)

The python is an important animal in San belief: humanity is descended from the animal, and the streams around Tsodilo were said to have been created during its search for water at the beginning of the world. This python figure was located in a difficult-to-access cave, and was heavily eroded suggesting its great age, and Coulson reports that all artefacts found in the cave, including bright red spear-points, were connected with ritual use:

"Stone age people took these colourful spearheads, brought them to the cave, and finished carving them there. Only the red spearheads were burned. It was a ritual destruction of artefacts. There was no sign of normal habitation. No ordinary tools were found at the site. Our find means that humans were more organised and had the capacity for abstract thinking at a much earlier point in history than we have previously assumed. All of the indications suggest that Tsodilo has been known to mankind for almost 100,000 years as a very special place in the pre-historic landscape."

Tsodilo thus seems to record some of the first human realisations towards something other than hunting, gathering and socialising: art opens here, as do perhaps early conceptions of beauty and the sacred, and the emergence of both the inner world and the world-beyond-sight held in common belief by all human cultures. One can easily imagine such cognitions beginning here and spreading outwards to the whole of humanity. Tsodilo and other Middle Palaeolithic sites in Southern Africa, such as Blombos and Apollo 11 Cave, are eloquent testimony to radical perceptual innovations which enabled anatomically- and cognitively-modern humans to outpace all other human species then currently living.

Sheila Coulson, Sigrid Staurset, and Nick Walker, Ritualized Behavior in the Middle Stone Age: Evidence from Rhino Cave, Tsodilo Hills, Botswana, PaleoAnthropology, 2011

David Lewis-Williams, The Mind In The Cave, Thames & Hudson, 2002

Patricia Vinnicombe, People of the Eland: Rock Paintings of the Drakensburg Bushmen as a Reflection of their Life and Thought, Wits University Press, 2009

Science Daily, World's Oldest Ritual Discovered -- Worshipped The Python 70,000 Years Ago, November 2006, url: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/11/061130081347.htm , retrieved Jan 2010

RSS Feed

RSS Feed