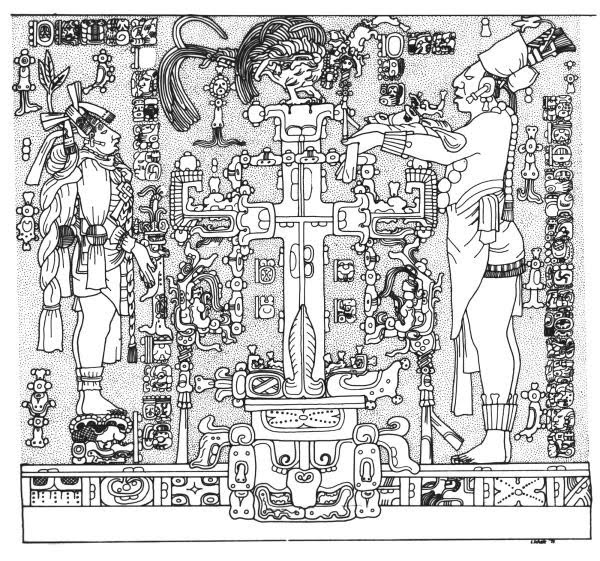

It has long been known that in the Classic Maya language of the inscriptions, the word for 'sky', chan, is often expressed or replaced with glyphs for 'four' or 'snake'. This wordplay, which has persisted in many modern Mayan languages across the centuries, happens to illuminate several previously-impenetrable Mayan images with meaning. Thus, for example the Classic Maya image of the World Tree as being bedecked with foliage with its cross like central bar represented as a double-headed serpent makes more sense when one considers that the Classic Maya translation of 'world tree' was wakah chan.

In modern Yucatec, too, a similar nexus of words exist: ka'an che', the 'sky tree' is also called the yax che', 'First Tree' and expressed as a verb, ka'an also means to 'raise up, elevate'. We have also seen previously in Yucatec the phrase yitz k'an 'cosmic sap', that spiritual substance which emerges from the blood during ritual to be offered to the gods in exchange for visions, and we have also heard of Ochcan (or och k'an) the Q'eqchi deity who initiates the apprentice into the final stages of becoming a shaman.

The sanctity of this nexus is underscored in modern Yucatec ritual: in making a xtab ka'an, an altar for rituals which literally means 'platform of the sky', the altar itself is suspended from ropes attached to four (Yucatec kan) poles representing the four directions. All of these point to a pan-Mayan understanding of the sky as not merely the roof of the world, but as an axis mundi from which is disclosed the deepest mysteries of life.

This linguistic resonance is broken, however, in both colonial and modern Tzotzil, partly for reasons of homophony (chan already has a variety of unrelated meanings from 'learn' and 'long-legged', although the wordplay between 'snake' and 'four' is partially present) and partly because the syllable k'an changed its meaning: k'anal now means 'star'. Thus a new word for 'sky' became necessary, and in finding one, the Tzotzil must have resorted to what may have been a common euphemism for sky, vinajel.

This word, while breaking the resonance of other Mayan languages, nonetheless discloses the same reality and understanding present in the above nexus, since it is clear to even a casual student of Tzotzil that the -el ending must be an attributive of a verb vinaj. A Tzotzil dictionary gives the following meanings:

vinaj vb. appear, be exposed, be seen, be heard, be distinguished, become known

Thus it is not too far a stretch to aver that vinajel might literally mean 'that which is seen, that which appears or is exposed'. The suffix -aj is itself a perfective ending, but in modern Tzotzil the root vin- takes no meaning on its own, however related words convey senses of 'reveal' which opens up a fascinating possibility that the Tzotzil word for sky might be taken to be synonymous with 'revelation'. Colonial Tzotzil adds an additional connotation to vinaj, that of 'manifestation' and 'discovery', while the related word vinajeb (with an archaic nominative suffix) means 'interpretation'.

We find words of similar meanings in the closely related Ch'olt'i language, such as the word tahvin 'to find, discover' and vinquilez 'raise up, sky', both of which use the syllable vin- while in the Classic Maya inscriptions, there is attested the word winb'aah 'image'. This latter word is made up of the root vin- plus b'aah or b'ah 'face, image, mask'.

These ideas disclose a fundamentally Mayan view of the heavens in contradistinction to the various Western approaches: the sky functions not merely as a theatre for astronomical events or astrological prognostications, but acts as a domain in which the individual can envisage himself in terms of a numinous realm of experience. The sky as revelation suggests an interactivity between the individual and the world, and between humans and gods, an inter-relationship of being not found commonly in the West.

Bruce Rimell, 2014

David Friedel, Linda Schele and Joy Parker, Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path, HarperCollins (Perennial), 1993

Robert M. Laughlin, The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantán, Smithsonian Institution Press, Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology #19, 1975

Robert M. Laughlin & John B. Haviland, The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of Santo Domingo Zinacantán with Grammatical Analysis and Historical Commentary, Volumes I & II, Smithsonian Institution Press, Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology #31, 1988

Peter Mathews and Péter Bíró, Maya Hieroglyphic Dictionary, entry for winb'ah, Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, url: http://research.famsi.org/mdp/mdp_detail.php?mayaSearch=&englishWordSearch=&spanishWordSearch=&TSearch=&TranSearch=&dateSearch=&letterSearch=W&englishSearch=&spanishSearch=&id=967&rootWord=winb%27ah&display=15&row, retrieved August 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed