Rather it unhinges those experiences from a foundation upon literal interpretations of the Classical Image, and centres both the Image and the experiences themselves not on the external cosmos but upon the human being, our neurological structures, our social realities, our propensity for ‘seeing into what is not, towards a perceived deeper truth’. Here we find clarity, and a third path opening before us.

Some fifty years later, Ermentrout & Cowan sought an explanation in terms of noise patterns and 'dark currents' emerging from within the human visual system itself, and utilised a complex mathematical treatment to demonstrate that the specific patterns seen were due to the interactions and reorganisations of these currents within the various geometrical structures of the retina, the optic nerve and the visual cortex of the brain.

The thesis is complex, not least because the neural structures are folded in complicated ways and Ermentrout & Cowan utilised logarithmic mathematical processes to arrive at their conclusions, but Meyers-Riggs provides a neat summary of some of the aspects. First, he discusses how noise currents, which he describes as representing excited cortical states in contrast to normal low-activity states, travel across the primary visual cortex (V1), the first layer of visual processing where retinal information arrives in the brain:

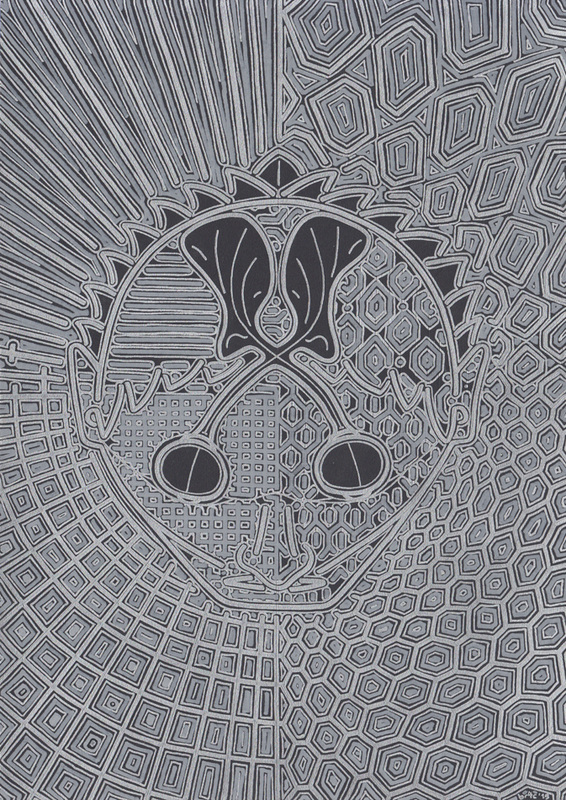

“We can think of it [the primary visual cortex] as a sheet of hypercolumns, cells sensitive to lines oriented in any direction. This surface is crinkled up like a ball of paper in your brain, but we can unfold it in a theoretical sense. These hypercolumns are linked together in a specific manner, which allows noise patterns of only certain types to form.... Four types of noise were found... i) the non-contoured roll, ii) the non-contoured hexagon, iii) the even contoured hexagon, and iv) the even contoured square.”

We might paraphrase these noise types more accessibly as i) sets of parallel horizontal or vertical straight lines, ii) loosely tessellating hexagons arranged in parallel lines, ii) strictly tessellating hexagons in a crystalline structure, and iv) strictly tessellating squares in a lattice structure. Next he states that biology provides an important clue as to how these patterns are mapped from the visual cortex to what is actually seen:

“Experiments have been done which allow mapping of how the visual cortex represents input from the retina. By stimulating a certain... region of the retina, the corresponding cells which light up in V1 can be measured. The easiest mapping... would be for the input of the retina to be represented as a flat sheet, which is then passed to the visual cortex like a photocopy. Instead, it turns out that the circular retina’s image is twisted and mapped in a slightly more complex manner to the flat surface of V1... [and] that straight lines in our visual cortex are mapped to curved lines in the retina, and vice versa.”

This mapping can be represented by a mathematical function called the complex logarithm and by applying this to mathematical descriptions of the four types of noise, Klüver’s form constants are strikingly liberated, elucidating a theory of

“...visual cortex noise twisted by the wiring between mind and eye. This hypothesis fits the fact that these high energy states may be caused by a variety of stimuli affecting excitability of the brain... It is compelling to think that these powerful symbols rely on no religion, no culture, and no time. They are a product of the fact that we… share the same biology.”

Earlier in our journey, we considered a quick and ready model of human perception as a series of filters which attenuated and modified sensory information and organised it into sensible three-dimensional realities to be presented to the consciousness, and noted the most recently evolved of these was a module for symbolic cognition. This model is useful, but we can see in our present context, there are limitations with regard to visionary experience as it implicitly assumes that raw data entering this system has its origin in the external world rather than from dark currents and noise within the neurological system itself.

Klüver's findings, and those of Ermentrout & Cowan, demonstrate that at least some aspects of visionary experience emerge naturally from a mathematical perspective on the interactions of noise and dark current data generated by the retina, optic nerve and visual cortex. This idea that at least some data may emerge internally modifies our Initial Model of Perception considerably and liberates several possible neurological forms of visionary experience: i) a vision consisting wholly of internal data, such as form constants or entoptics, closed eye visuals, ii) a vision consisting of the fusion of internal and external data, such as with open-eye visuals and iii) a vision consisting of or responding to this fusion which is then irregularly modified or follows unexpected neural and modular pathways before being presented to the consciousness. In some respects, this resembles an influential model of perception formulated by David Lewis-Williams.

Martindale postulated in 1981 that in the transition from waking consciousness to unconscious deep dreamless sleep, human beings pass through six distinct states of consciousness: realistic fantasy, autistic fantasy (by which is meant flights of fancy and other states whose structures bear little resemblance to external reality), reverie (directionless image-based fantasy), hypnagogic states and dreaming. Lewis-Williams questioned their distinctiveness and considered Martindale to have imposed the six stages on what was rather a continuous spectrum of consciousness proceeding gradually from wakefulness to unconsciousness, and reports that Charles Laughlin considered our experience of the movements between these states to be fragmented rather than seamless in both waking and sleeping life, often jumping abruptly from one state to another without necessarily realising.

Lewis-Williams calls this spectrum the 'normal trajectory' of consciousness and it may perhaps be associated with normal, low-activity cortical states narrated above, but in addition to this, he postulates an 'intensified trajectory' (perhaps generated by excited cortical states) associated with visions and hallucinations that are experienced when one is nominally in a situation of wakefulness.

In this latter 'intensified trajectory', the spectrum precedes from wakefulness to fantasy, before departing from the 'normal trajectory' into three stages of i) entoptic phenomena, in which form constants and other intraneural geometric patterns are seen, ii) construal phenomena, where these patterns are construed into iconicity, by which is meant half-formed images constructed partially using the dimensional and narrative models of the external world inherent in the various information-processing modules of the brain, and a state in which these images are sometimes overlaid upon the external world in a kind of neurological simultaneity, and finally iii) hallucinations, or we might say 'visions', in which fully-formed internal worlds and narratives are experienced as divorced from the external world entirely.

These intensified states he considers to be those which are commonly termed 'altered states of consciousness' while noting the Western rationalist bias inherent in this phrase: 'intensified trajectory' thus reflects his belief that the entoptic, construal and hallucinatory phases here are conceived as more intense and focussed experiences than dreams or any other aspect of the 'normal trajectory'.

The entoptic states seem from the very name given to them, derived as it is from the Greek εντος 'within' and οπτικος 'visual', to correspond to Klüver's form constants emerging from the structures of the visual system, but the second state, that of the 'construal' perhaps requires some explanation. Lewis-Williams remarks that in this stage:

“...subjects try to make sense of entoptic phenomena by elaborating them into iconic forms, that is, into objects that are familiar to them from their daily life. In alert problem-solving [waking] consciousness, the brain receives a constant stream of sense impressions. A visual image reaching the brain is decoded... by being matched against a store of experience. If a 'fit' can be effected, the image is 'recognized'. In altered states of consciousness, the nervous system itself becomes a 'sixth sense' that produces a variety of images including entoptic phenomena. The brain attempts to decode these forms... [in a] process linked to the disposition of the subject.”

Thus in the construal state, the half-images that emerge may be related to the individual's mood, previous experiences, belief systems or cultural worldview, but are primarily local and often associated with those aspects of the subject's life which have occurred incidentally or recently. This is strongly contrasted with the final, 'hallucinatory' or visionary phase in which:

“...marked changes in imagery occur. At this point, many people experience a swirling vortex or rotating tunnel that seems to surround them and to draw them into its depths. There is a progressive exclusion of information from outside...”

The description of this vortex is often culturally conditioned: where Westerners recognize this image as a tunnel or corridor, indigenous peoples might conceive of a hole in the ground, as voyaging into the sea, rising up through the smoke-hole in the roof of a communal living space or entering a spirit world through the centre of a mirror. That its origin is as similarly neurological as form constants is highlighted by Cowan & Bressloff, since:

“...the visual world is mapped onto the cortical surface in a topographic manner, which means that neighbouring points in a visual image evoke activity in neighbouring regions of visual cortex. Moreover, one finds that the central region of the visual field has a larger representation in V1 than the periphery... partly due to a non-uniform distribution of retinal ganglion cells.”

As such in the 'intensified trajectory' in which the neural system acts as its own sixth sense, we should expect visual responses to be more vivid in the centre of the field of view, liberating a perceived brightness which contrasts with less vivid responses in the peripheral regions. This situation is then re-cognized as tunnels and the other culturally conditioned forms mentioned above. Lewis-Williams continues:

“Stage 3 iconic images derive from memory and are often associated with powerful emotional experiences. Images change one into another. This shift in iconic imagery is also accompanied by an increase in vividness. Subjects stop using similes to describe their experiences and assert that the images are indeed what they appear to be. They lose insight into the differences between literal and analogical meanings.”

This latter point is of striking relevance to our whole theme, and echoes what Strassman, Noll and many others have noticed in visionary subjects, that there comes a point in which the visionaries wholly consider that what they are seeing is real. We might speculate that this apparently reality is due to the neural pathways taken by the visionary data, traversing through the various processes of modular interpretation and symbolic cognition, within the brain closely mirroring the pathways taken by stimuli from the external world.

“Nevertheless, even in this... stage, entoptic phenomena may persist: iconic imagery may be projected against a background of geometric forms or entoptic phenomena may frame iconic imagery. By a process of fragmentation and integration, compound images are formed... [such as] a man with zigzag legs. Finally, in this stage, subjects enter into and participate in their own imagery: they are part of a strange realm. They blend with both their geometric and their iconic imagery... [and] sometimes feel themselves to be turning into animals and undergoing other frightening and exalting transformations.”

Such compound images and transformations surely must be regarded as one of the primal sources of many of the human-animal, human-botanical and other surreal hybrids found throughout the art traditions of the world in all time periods since the Palaeolithic. In my own experience, I cannot avoid comparison between Lewis-Williams' words here and the imagery seen in salvia divinorum visions which appears to proceed directly to this most intense and self-transformative stage of the iconic phase.

Such an accurate and illuminating description of the basal totality of the human visionary experience, springing from an analogical and neurological perspective rather than a literal view, enriches our discussion profoundly and resonates deeply with the notion that the primacy of visionary experience is to be placed upon the human and upon our neurology rather than upon an external or 'objective' realm.

One question remains however. It is be noted that non-human animals possess similar cortical structures and neural pathways, and in the case of primates, strikingly human-like brains in some respects, and thus it could be concluded that similar internal experiences, particularly in the case of form constants or the 'entoptic' stage, might be possible.

Why, then, are humans the only creatures to ascribe any significance to them or respond to them behaviourally in any way, despite their emergence from “no religion, no culture and no time”? There must surely be a crucial piece of cognitive architecture that is present in humans but absent in others, a 'specific' (in Darwinian terms) that contrasts with or extends from the 'generic' of our shared intelligence with primates. The missing link is symbolic cognition, and its import and centrality to our present thesis will quickly become apparent.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed