Huichol yarn paintings are justly famous in the world of anthropology and visionary art, expressing as they do the shamanic realities of peyote visions, and the sacred pilgrimages and myth cycles of the Huichol people. There are several notable modern yarn painters, the most celebrated perhaps being José Benítez Sánchez, an initiated shaman whose shimmering and detailed images have been exhibited in America and Europe and whose work is sometimes considered representative of the artform in its full expression of the sacred complexes underlying the peyote vision and the Huichol perceptual cosmos.

However, Ramón Medina Silva lived a generation before this widening celebration of Huichol art had come to pass, and he along with his wife Guadalupe de la Cruz Ríos (known as Lupe) were key innovators of Huichol folk arts into the narrative and visionary artforms well-known today.

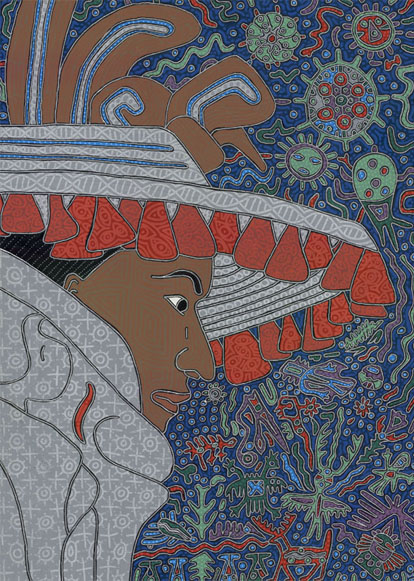

Ramón is here depicted deep in trance, gazing at his peyote visions.

As part of his 'completion' as a shaman, Ramón led several pilgrimages to Wirikuta for the famous Peyote Hunt, and although it is not certain whether by the time of his death he had completed the full six pilgrimages usually required to attain the full status of mara'akáme, MacLean reports that even from his first pilgrimage, he developed shamanic abilities very quickly. Furst states however that he completed his training in 1968.

Ramón and Lupe met as migrant labourers in Nayarit, married in the late 1940s and moved to Guadalajara in 1961, where they met the Franciscan Padre Ernesto and began selling traditionally-made crafts through the Basilica of Zapopan where the priest lived. By the mid 1960s, Ramón and Lupe had met American anthropologists Peter T Furst and Barbara G. Myerhoff, and the four began an inter-cultural collaboration that was to propel them into academic notability.

Furst says that previously, Huichol people had tended to use yarn painting as as a decorative tool for items like bowls, or as a folk art, using Huichol motifs with no particular significance that Ramón called puro adorno 'pure decor'. Before 1965, both Ramón and Lupe had had success with this type of work, and Lupe was already an accomplished weaver, but Ramón was to turn the yarn painting into a two-dimensional narrative and visionary artform, as Furst recounts:

“But one day in the summer of 1965, with a little prodding from this writer and Padre Ernesto, yarn painting took a new, radical turn, from puro adorno to pictorial narrative. Why not use his art, we asked Ramón, to illustrate his stories and his vision? Puzzled at first, Ramón, who was then well into self-training as a shaman, produced a yarn painting two days later [The Soul's Arrival In The Village Of The Deceased] that went with a story of the journey of the soul after death...”

Fowler Museum of Cultural History

From the outset, Ramón used the Huichol word nieríka (plural, nieríkate) to refer to his new narrative yarn paintings, a word with many layers of meanings “connected with the spiritual and the realm of deities and ancestors... It can be understood as mirror, likeness, face, aspect, image of Otherworlds, and conversely as the doorway or portal into 'non-ordinary reality', the realm of the divine, creation and transformation.”

Schaefer (through MacLean) also reports that nieríka can refer to a person's predestined skill or knowledge, and that almost any object that symbolises or manifests the sacred or the supernatural can be considered as nieríka, from ancient rock art to a shaman's basket, from offerings and votive bowls to mirrors and images of deities. Furst adds that “...from the moment the yarn painting ceased to be merely décor and... began to mirror the sacred myths and the artist's visions, it joined the exalted company of nierikate.”

Furst and Myerhoff soon arranged an exhibition for Ramón's work at the UCLA Museum of Ethnic Arts in 1968, the first time Huichol art had been shown outside of Mexico. Ramón and Lupe went to Los Angeles to attend the opening. MacLean reports something of his presence on the trip:

“Myerhoff took them to a department store and found that all eyes went to Ramón, even though he was dressed in American clothes: 'He had a presence that was extraordinary... the glance of kings... There are people who have this sense of another realm, and they moved differently through this realm because of it'.”

and Lupe ritually preparing the painting for completion. Peter T. Furst

What, then, of Ramón's body of work, which survived him and allowed his visions to be communicated to the wider world, for what purpose was it created, and how does it compare to the wider Huichol sphere of experience?

Myerhoff narrates that, for the Huichol, “...it is not proper to tell others one's peyote visions unless one is a mara'akáme. Only the latter's visions are intended to convey religious information... The ordinary [person's] visions are for beauty's sake alone, intensely private and spiritual but less sacred than those of the mara'akáme, whose privilege and duty it is to share his messages in great detail.”

Thus we see that for shamans like Ramón, communicating their visions was an important task, and his innovation of doing so visually allowed the audience not merely to imagine but to visually experience the essence of his vision. Just as the shaman enters the Otherworld through a portal called nieríka, so the viewer can also enter through the yarn painting, also called nieríka. Myerhoff also recognised that the knowledge of Huichol culture she learned from Ramón, and by implication the subject matter of his yarn paintings, was heavily coloured by his status as a shaman and unlikely to have been shared by the typical Huichol.

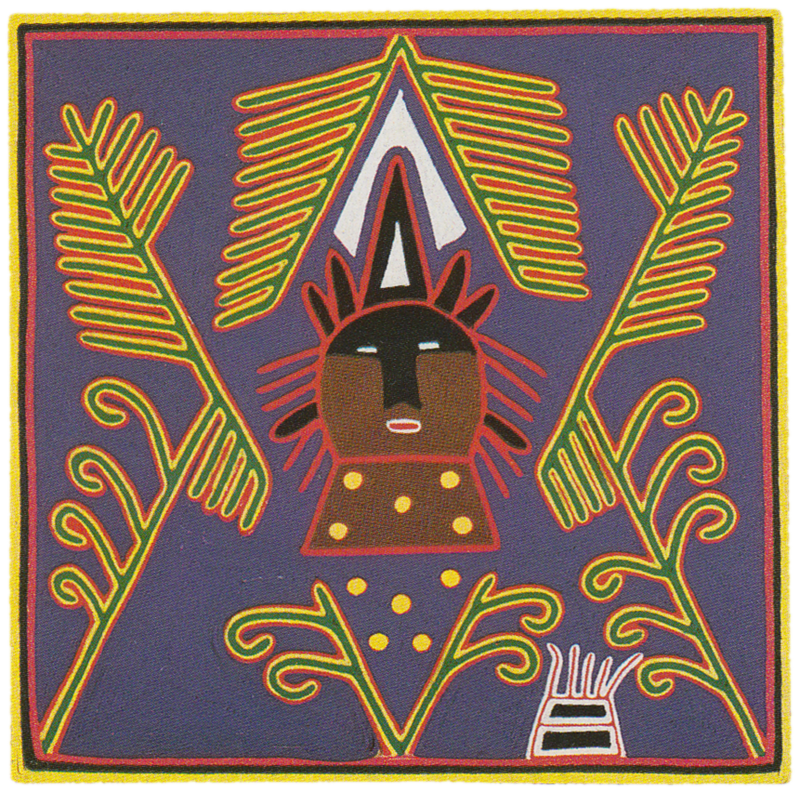

The images reflect this – Tatewarí, our Grandfather Fire, the ancestral embodiment of, and teacher to, the shaman features commonly, as do expressions of devotion to hikuri the sacred peyote and journeys into the Otherworldly village of the dead. Offering pieces, or images that venerate the subject in a sacred manner are also seen as well as visionary works. The visual style is strongly dictated by Huichol interpretations of the effects of peyote vision: we see figures surrounded by glowing colours and vibrant lines of magical power emanating from sacred personages and plants. Shamans engage in communion with deities, whose form (particularly Tatewarí) seems to be in constant movement and transformation.

Three peyote seen in vision, depicted in X-ray style with their roots and the button showing,

and emanating glowing rays of magical power. Peter T. Furst

“The idea that paintings are based on dreams and visions is a simplified interpretation of the Huichol concept of shamanic inspiration in art... [Huichol] artists themselves were less interested in whether a particular painting was the product of a particular dream, vision or other form of inspiration; instead they considered the artist’s heart-soul-memory (called iyari in Huichol) to be the most important factor in making art. If the iyari was open and in communication with the gods, then the art was shamanically inspired.”

Furst narrates how Ramón used the term kupuri iyari, meaning approximately 'heart and soul', although kupuri refers more to the soul that leaves the body after death (or to the travelling soul of the shaman) whereas iyari connotes a life-essence or memory which returns to the earth. Here, then is something of an authentically Huichol way of viewing these artworks: not as individual visions or simply as expressive images, but as open portals, nieríka, of experience into the shamanic world-beyond-sight communicated through the heart-and-travelling soul of a 'completed' shaman.

There is something in this notion of kupuri iyari which resonates with the perceptions of many contemporary visionary artists – to create holistic shimmering portals rather than mere pictures – and I suspect the concept is not confined solely to Huichol tradition. Whether modern Western culture can create a space for such sacred/interactive subtlety in artistic endeavours (that is to say, to move beyond simple amazement at something exotic or esoteric and even to transcend admiration for detailed craft) remains to be seen. I believe that a wider appreciation of the self-evident authenticity and honesty of purpose residing in Ramón's work would certainly aid many in coming to a deeper – or rather, archaic – understanding of what art is really for.

“The mara'akáme, we call him Tatewarí. He is Tatewarí, he who leads us... It is the mara'akáme who directs everything. He is the one who listens in his dream, with his power and knowledge. He speaks to Tatewarí... who tells him everything, how it must be...”

- Ramón Medina Silva, Huichol shaman, visionary artist, luminary

Fowler Museum of Cultural History

Fowler Museum of Cultural History

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

Fowler Museum of Cultural History

Fowler Museum of Cultural History

Right: How One Person Received A Huichol Name, Ramón Medina Silva, 60cm x 60cm, date unknown

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of Berkeley

Joseph Campbell, Historical Atlas of World Mythology, Vol II: The Way of the Seeded Earth, Part 3: Mythologies of the Primitive Planters: The Middle and Southern Americas, Harpers & Row Perennial Library, 1989

Dhushara (Chris King), Genesis of Eden: A Tribute to Ramón Medina Silva, Carlos the Coyote and Maria Sabina, url: http://www.dhushara.com/book/genaro/genaro.htm , retrieved August 2010

Peter T. Furst, Visions of a Huichol Shaman, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2003

Joan Halifax, Shamanic Voices: A Survey of Visionary Narratives, Penguin Arkana, 1979

Hope MacLean, Huichol Yarn Paintings, shamanic art and the global marketplace, Studies in Religion / Sciences Religieuses, Vol. 32/3, 2003

Hope MacLean, The Shaman’s Mirror: Visionary Art of the Huichol, University of Texas Press, 2012

Sandy McIntosh and Randy Stark, Conjuring Brujos: Did don Juan and don Genaro Exist?, Part 3 An interview with Barbara G. Myerhoff, url: http://sustainedaction.org/Explorations/conjuring_brujos_pt_3.htm, retrieved August 2010

Barbara G. Myerhoff, Peyote Hunt: The Sacred Journey of the Huichol Indians, Cornell University Press, 1974

Barbara G. Myerhoff (trans.) and Ramón Medina Silva, How the Names Are Changed on the Peyote Journey, url: http://nagualli.blogspot.co.uk/2013/01/Ramón-medina-silva-how-names-are.html , retrieved January 2014

Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hoffman and Christian Rätsch, Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers, Healing Arts Press, 2001

RSS Feed

RSS Feed