Japanese however has no such concept in its lexicon: there are words which are somewhat similar, such as kashikoi 'clever, smart, wise, intelligent', umai 'skillful, clever, expert' and in Classical Japanese of the Heian Period, satoshiki 'clever, perceptive', but these words do not relate to knowing or having seen. Rather they relate lexically to, respectively, 'having grace or humility', 'being generally good or excellent' and 'having realised in a meditative manner' (compare satori, the Japanese translation for 'enlightenment'). Japanese is here sufficiently different from the Indo-European cultural sphere for an appreciation of this difference to be evident.

We find, for example, in Rothenburg's translations of The Life Of María Sabina, in speaking of the various words for shaman, that:

“The native words are chota chjine (wise person, Wise One, or doctor). Among the Mazatecs are found three categories of curers... the Sorceror (tji'e) who is said to be able to transform himself into an animal at night... the Curer (chotaxi v'e'nta) who uses massage, potions and devices such as his own language in which he invokes the Lords of mountains and springs... [and] in Huautla there is the Wise One and doctor (chota chjine) who doesn’t do evil or use potions to cure. His therapy – or hers – involves the ingestion of mushrooms, through which he acquires the power to diagnose and cure the sick person..” (1)(2)

Again we find in Munn's seminal essay The Mushrooms of Language quotes from the song of shaman Irene Pineda de Figueroa:

“Woman of medicines and curer, who walks with her appearance and her soul," sings the woman, bending down to the ground and straightening up, rocking back and forth as she chants, dividing the truth in time to her words: emitter of signs. "She is the woman of the remedy and the medicine. She is the woman who speaks. The woman who puts everything together. Doctor woman. Woman of words. Wise woman of problems."

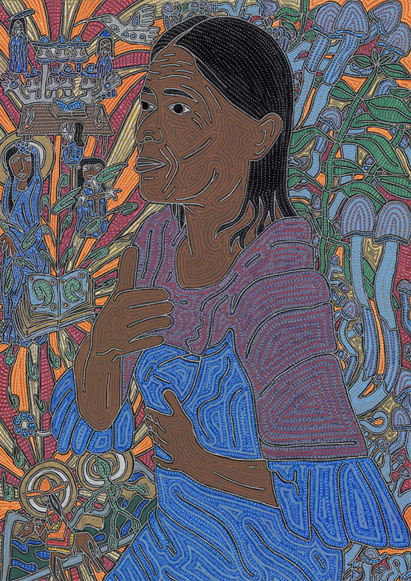

And again, in an essay on the uniqueness of María Sabina, the famous shaman from Huautla de Jiménez:

“When Maria Sabina says she is a chjon chjine xki, chjon chjine xca, chjon chjine en, chjon chjine khoa 'woman wise in medicine, a woman wise in herbs, a woman wise in words, a woman wise in problems' , she is stating her culture's concept of the shaman's role...”

Repeatedly Munn appears to translate the speech of Mazatec healers as referring to 'wise men', 'wise women' and wisdom, and in each case he is translating the Mazatec word chjine. Tarn and others have critiqued Munn's and Rothenburg's ethnopoetic attempts to recast Sabina and Pineda de Figueroa as visionary poets, while Halifax has taken a more functional view that here they are simply presenting their credentials to the spirit world. Thus it is ironic, while María Sabina states her culture's concepts above, Munn's and Rothenburg's preoccupation with wisdom and poetics subtly misses a fundamental aspect of Mazatec perceptions of shamanic function.

We find clarity in Carole Jamieson Capen's bilingual Mazatec-Spanish dictionary of the dialect spoken in Chiquihuitlan, a remote village some 50km from Huautla de Jimenez in the mountainous Mazatec territory. In the orthography that Capen utilises, chota chjine becomes xuta chjine, xuta being a dialectal variation of chota and simply meaning 'person'. In the entry for chjine, however, we find an authentic portal into an indigenous worldview. It is given here in full, with English translation:

vëhëchjine vb. prepara [prepare, make ready]

tsajin tjin chjine comida no había comida preparada [the food wasn't ready]

café chjine café preparado [prepared coffee, coffee ready to drink]

chjine (2), s. maestro en (artesano) [master in (artform)]

chjine ndyaja pirotécnico [firemaker]

chjine tyjo musico [musician]

chjine ya carpintero [carpenter]

When following a noun, as in the first definition, it carries connotations of being ready, completed, prepared; these notions are extended in the second definition, in which chjine occupies the initial position, into tendencies of skill and talent, of occupation, and of the status of maestro. Thus, chjine discloses not the stative intention of the English word 'wise' but a more active engaging sense: a wise person may well be One Who Knows, but that knowing is often conceptual, theoretical or of the nature of potential. By contrast, chjine represents a readiness to action just as maestro represents not wisdom but profound talent and a completedness of training. Chjine remains in the field of potential but it is a deeper, more realised potential. It is as different from 'wise' as stative is to active. In this light, we might posit the following translation:

chota chjine : a person who is prepared for something, a person who excels in doing a certain thing, a master or mistress in a certain art, a person who has been completed [in their understanding or skill]

Interestingly, one of the Mazatec words that corresponds to 'knowing', vëë, is synonymous with both 'seeing' and 'seeming', while another, ma (or ma rë) connotes both 'knowing' and 'ability'. A third word cjuahasen 'intelligence' is related to cjuaha 'grasp, grab'. Thus, chjine not alone in the understanding that 'knowing' or 'readiness' directly relates to the potential for action, and a subtle subjectivity is woven into the first example, where seeing and seeming coincide.

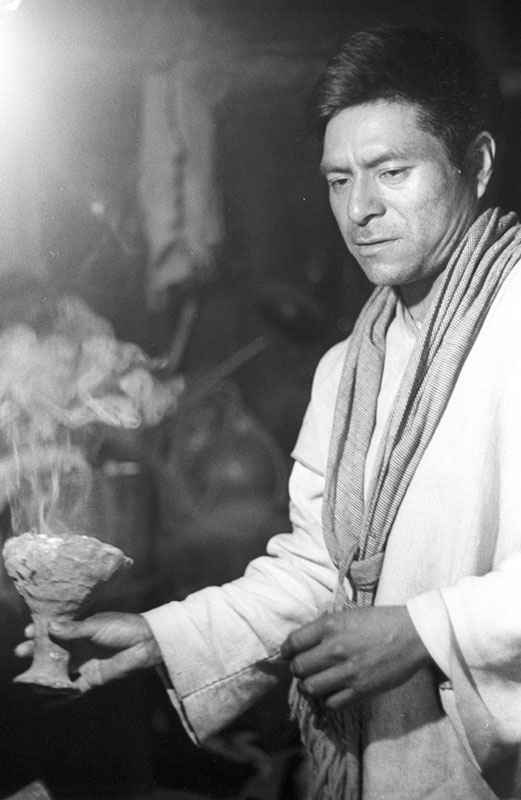

mara'acame s. cantador, cantador sacerdote huichol [singer, priest singer of the Huichol]

tunúiya vb. cantar para curar [sing to cure someone]

tunúame s. cantador [singer]

'uhaye s. medecina, veneno, remedio [medicine, venom, remedy]

'uhayemarica v. curar, trater enfermidad [cure, treat the infirm]

tiyu'uhayamavame s. curandero, medico, doctor [curer, medic, doctor] (3)

However, there is something odd here in the word mara'came, since it seems not to link to any other aspect of the vocabulary. Given that the suffix -(a)me appears to be an agentive, we can see how the Huichol word tunúiya liberates tunúame 'singer', but even though tunúiya has a shamanic meaning, the derivative tunúame lacks such a connotation. Instead we find that the cantador sacerdote huichol is predicated upon an otherwise unknown verb *mara'ac(a)- or perhaps *mara'aquiya. I can find no reference for these apparent words, and can only assume it is an archaism whose meaning is no longer transparent in modern Huichol. An entry in the dictionary for maraíca 'aura, spirit energy' is suggestive of *maraíca-me but this word is also not attested anywhere, and it is probably unwise to assume a connection based on superficial phonetic similarity.

Neither Myerhoff nor McLean in their respective studies of Huichol religion and art clarify this oddity, but it is nonetheless plainly to be seen that the words relating to shamanism have an eminently practical and active connotation, as with the Mazatec. The shaman is one who sings, one who deals with medicine, one who cures. The Huichol focus is upon concrete actions, and stative or theoretical notions of wisdom are nowhere seen.

Huichol is an Uto-Aztecan language, as is Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, and the same practical focus upon action is seen in this language also, as these words from the Classical language elucidate:

tlachiya observe, gaze watch, look

tepahtiquetl doctor, curandero, shaman

pahtia pay, cure, restore

ixpahtia apply medicine to the body or wound

tlapahtilia apply herbicide to someone's cornfield (4)

Interestingly, in Colonial Tzotzil of the 16th century, we find the verb 'il has other connoations besides seeing, and words deriving from 'il may explain the appearance of the suffix -ol in the modern form:

'ilel appearance, form, style

'iloj witness, experience, see

j'ilojel witness, one who has seen or experienced (5)

However, a more earthy notion, similar to the Mazatec chota chjine, is seen in two Yucatec Maya words for shaman, the first being hmen, which Bolles denotes as literally meaning 'one who makes', and the second hmendzac 'one who makes medicine'. Here the agentive h- (written as j- in Tzotzil orthography but with the same pronunciation) is seen with a verb men:

hmendzac one who makes medicine

hmenzacal one who does weaving

hmentunich singer

hmenche carpenter

For the indigenous shamanic lifeways of Mesoamerica do not partake of lofty grandeur or castles in the sky. Those shamans are not Wise Ones or Ascended Masters, but folks who work with medicine, ones who are makers, creators, completed in their seeing, those who watch carefully and find what they were looking for. They are the Ready Ones, the chota chjine, and I believe it is profoundly important for the contemporary Western seeker of visions to remain in contact with this practical way of seeing, for in this way we can deepen the authenticity of the visions we seek. To aim not to be wise, but to be ready.

(2) Translations of the two other terms in Munn's summary are elusive: tji'e 'Sorceror' is lacking in Capen's otherwise comprehensive dictionary, while chotaxi v'e'nta 'Curer' may be a foreshortened and corrupted version of xuta (xi) vincha nascuan 'one who provides tobacco'.

(3) Huichol pronunciation is fairly straightforward, with only the apostrophe denoting the glottal stop being of any difficulty.

(4) Classical Nahuatl pronunciation is as follows: both c and qu denote 'k', ch, p, t and all the vowels being pronounced as expected. The letter h represents a glottal stop and the digraph tl is a lateral semi-click, similar to the 'ttl' in a carefully-pronounced 'bottle'. I have omitted the long-vowel markers here.

(5) Tzotzil pronunciation, both colonial and modern, is straightforward. As with Mazatec, the j is pronounced as in English 'h', and the apostrophe is a glottal stop, such that j'ilol is pronounced as 'hˀee-lol'. Yucatec replaces j with h and hmendzac is pronounced as 'hmen-tzak'.

David Bolles, The Shamans of Yucatan, Mexico, Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, 2005, url: http://www.famsi.org/research/bolles/shamans/index.html , retrieved April 2014

Álvaro Estrada & María Sabina, The Life of María Sabina, in Jerome Rothenberg (ed.), María Sabina: Selections, University of California Press, 2003

Joan Halifax, Shamanic Voices: A Survey of Visionary Narratives, Penguin Arkana, 1979

Carole Jamieson, Gramatica Mazateca del Municipio de Chiquihuitlan, Oaxaca, Instituto Linguístico de Verano, Gramáticas de Lenguas Indígenas de México #7, 1988

Carole Jamieson Capen, Diccionario Mazateco de Chiquihuitlan, Oaxaca, Instituto Linguístico de Verano, Serie de Vocabularios y Diccionarios Indígenas 'Mariano Silva y Aceves' #34, 1996

Robert M. Laughlin, The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantán, Smithsonian Institution Press, Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology #19, 1975

Robert M. Laughlin & John B. Haviland, The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of Santo Domingo Zinacantán with Grammatical Analysis and Historical Commentary, Volumes I & II, Smithsonian Institution Press, Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology #31, 1988

Juan B. McIntosh & Jose Grimes, Vocabulario Huichol-Castellano y Castellano-Huichol, Instituto Linguístico de Verano, 1954

Hope MacLean, The Shaman’s Mirror: Visionary Art of the Huichol, University of Texas Press, 2012

Henry Munn, The Mushrooms of Language, in Michael J. Harner (ed), Hallucinogens and Shamanism, Oxford University Press, 1973

Henry Munn, The Uniqueness of Maria Sabina, in Jerome Rothenberg (ed.), María Sabina: Selections, University of California Press, 2003

Barbara G. Myerhoff, Peyote Hunt: The Sacred Journey of the Huichol Indians, Cornell University Press, 1974

Bruce Rimell, Chjine: A Mazatec Concept of Practicality, 2006, url: http://www.biroz.net/words/chjine.htm , retrieved April 2014

Nathaniel Tarn, Review of María Sabina: Selections, Jacket Magazine, 2004, url: http://jacketmagazine.com/25/tarn-sab.html , retrieved April 2014

Stephanie Wood, John Sullivan et al, Nahuatl Dictionary, Wired Humanities Project, url: http://whp.uoregon.edu/dictionaries/nahuatl/ , retrieved April 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed