With these words, the Roman poet Ovid narrates in his Metamorphoses the mythical moment when Orpheus descends to the Underworld to retrieve the soul of his dead wife Eurydice and in so doing, recalls the foundation for the mystic traditions of the Orphic religion. We may note the subtle female orientation here in the phrasing 'Persephone and her lord' but it is the image of descent-and-emergence, a ubiquitous image in the Mystery traditions of Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean, which interests us here.

There is in this mythical image, if not in the narrative details, a striking parallel between Orpheus and the story from Eleusis, of Persephone's kidnap by Hades and her return to the world through the grief of Demeter and the conveyance of Hermes. It is in particular the image of the male leading the female from the Underworld that is notable here, and although at Eleusis, an earlier mythical substrate appeared to exist in which Demeter rather than Hermes led Persephone back into the light, and although the Orphic religion emerged relatively late in Aegean history, it is an image which appears in a number of myth systems of the Mediterranean and Near East, and for less patristic reasons than we might imagine.

Illuminating the Orphic story with an Eleusinian light, we can quickly start to see Orpheus the initiator as Hermes, the ultimate initiator into (and out from) life. Both cross the realms of life and death with relative ease, and both were noted lyre players: indeed the Homeric Hymn to Hermes claims the god invented the instrument in a direct challenge to the more customary patronage of Apollo. Episodes in which Hermes the Thief used his lyre-playing ability to charm the owners of cattle (including Apollo) and thereby steal them have direct parallels with Orpheus's own musical ability.

Roman copy, c.50 BC, from a Greek original c.425 BC

Penthelic Marble, Louvre Museum, Paris

“In the light of its initiations...Orphism may be characterised as a kind of private religious exercise. The mythical prototype expressive of this tendency was the figure of Orpheus, who was not only a solitary singer but also an initiator of men and youths.”

Among the Orphics, the ritual was to follow Orpheus into the Underworld, there to experience being reborn by dying to oneself in the realm of death. This personal salvation was accompanied by wisdom teaching which, it was said, had come from Orpheus himself and the experiences he gained in his descent and re-emergence.

By contrast, at Eleusis, the celebrants did not descend into the dark. Rather they shared in the rage and world-destroying grief of the goddess Demeter, remaining upon the earth and mourning for the loss of the innermost part of her soul symbolised by her daughter. Ritually re-enacting her desperate search across the world, they cried, grieved and danced in an experiential disordering of the senses to prepare for the visio beatifica which marked the arrival of Persephone back into the world. In returning, Persephone did not drag the celebrants down into the Underworld, instead bringing with her magic of chthonic rebirth and transformation in the person of Plouton into the realm of the living.

For the Orphics, it almost seems as if the loss of Eurydice is of little importance, for it was Orpheus's journey which provided the mythical precedent for the religion, and the image of his wife's return seems irrelevant to the concept of personal salvation. But at Eleusis, Persephone's ascent from the Underworld, and her reuniting with her Earthly Mother Demeter and then recombination with Rhea, Queen of Heaven and Mother of the Gods, effects something much greater: a Cosmic Salvation that transformed the entire Greek world. The Orphic focus on the individual may explain in part Plato's hostility towards the story of Orpheus, particularly as he was known to be an Eleusinian initiate.

From the standpoint of the aforementioned image of the male leading the female into the light, we might argue that Orpheus, being mortal, fails in his quest where the immortal Hermes succeeds, but there is another difference too: in the female-oriented Eleusinian image, Hermes's role is minimal. He arrives, descends, returns Persephone to the world, and exits the story. His role is not the prime focus, as it is in the Orphic. Hermes here seems not so much a male hero so much as an agent of change in the female psychic space at Eleusis.

This is Jungian territory: Hermes here resonates with the Animus, the archetype that represents that collective 'male' qualities experienced consciously or unconsciously within the 'female' psyche. Jung divided the development of the Animus into four stages, beginning with the personification of physical power before moving through images of romance and oratory, before culminating in the experience of the Animus as Helpful Guide, or magical helper in Campbell's monomythic terms, likening this final stage to the mytheme of Hermes.

And indeed, when comparing the Eleusinian and Orphic images from this perspective, it is difficult not to see Orpheus as the orator (or perhaps even the romantic) and Hermes as the ultimate guide, moving the celebrants into the fullest spiritual understanding of the female-driven Eleusinian narrative. He is here neither saviour nor teacher, but the mythical figure whose only function is to change the experiential state of being.

The image of Animus as Helpful Guide in female psychic spaces also finds resonance in an introductory tale from the Sumerian cycle of Inanna. Much is lost here – the clay tablets upon which the myths have been preserved are fragmentary, but it seems reasonable to suggest a kind of mystery tradition may have surrounded the image of Inanna, particularly in her famous exploits to become Mistress of the Underworld.

But it is the less well-known story of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree which illustrates our present point. The story, which takes place at the very beginning of the world's creation, is worth exploring in some detail. Soon after the heavens and Earth had been separated, there appeared upon the banks of the Euphrates a certain tree, called the huluppu, whose species has not yet been identified. Inanna walks along and immediately desires the tree for her garden:

I shall plant this tree in my holy garden...'

“Inanna cared for the tree with her hand,

she settled the earth around the tree with her foot.

She wondered: 'How long will it be

until I have a shining throne to sit upon?

How long will it be

until I have a shining bed to lie upon?'”

But though the tree continues to grow for many years, and though Inanna waits, the tree does not bear the fruit Inanna desires. Instead it births three fearsome beasts:

made its nest in the roots of the huluppu tree.

The anzu bird set his young in the branches of the tree,

and the dark maid Lilith built her home in the trunk...

“The young woman who loved to laugh wept.

How Inanna wept!

Yet they would not leave her tree...”

he carved a throne for his holy sister,

from the trunk of the tree

Gilgamesh carved a bed for Inanna...”

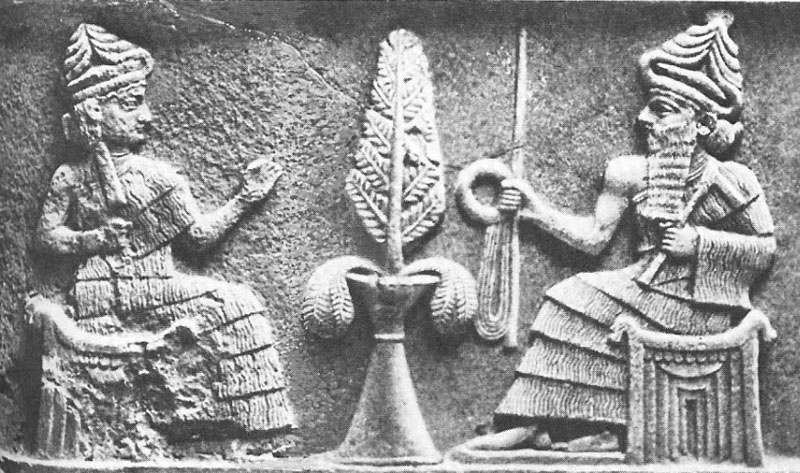

Stele of Ur-Nammu, Ur, 2050-1950 B.C.

The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

This is perhaps contrary to our modern expectations of Man the Saviour. We might expect Inanna, having been saved from the beasts of the tree by Gilgamesh, to marry him and live happily ever after, but in this female psychic sphere she instead wanders the world advertising her sexuality, eventually choosing the young shepherd Dumuzi as her husband. That Gilgamesh makes no further appearance in her story indicates his role not as Saviour but as Guide to a transitional moment in the story.

Wolkstein's psychological interpretations illuminate these points:

“...Inanna, who was born of divine parents, has descended to earth and waits as a 'young woman' for her throne and bed. Inanna waits; but her tree does not come into the fruition she wishes. Instead it becomes the habitat of Inanna's unacknowledged, unexpressed fears and desires...”

A notable aspect here is that by the time the Inanna Cycle of stories has finished, Inanna will through her actualised desires and heroic actions find herself as Queen of Heaven, Earth and Underworld. The appearance of the three beasts in the tree as symbolising these three realms prefigures in some senses the narrative action of the whole of her adventures. This prefiguring is specific in its imagery: in another tale, the anzu bird tries to capture the me, the symbols of civilisation, while Lilith is a mirror image of Inanna, exciting as she does fear rather than wonder, horror rather than reverence.

Wolkstein suggests the image of the serpent represents the forces of sexuality and rebirth, untameable by Inanna in her state of innocence. She continues:

“Inanna dissolves into tears at the realization of her own dark solipsistic cravings... But weeping has little effect on the creatures who will not be tamed. After intense and repetitive weeping, Inanna's own resistances weaken and she is prepared to move into another state of awareness. At dawn, with the renewal of light and consciousness, she asks for help...

“Although Gilgamesh has not come into his full development [in this story]... he is nevertheless Inanna's initiator, for he brings courage, decisiveness and strength to Inanna in her moment of weakness. With her consent, he rids the young woman of her 'creatures of the wilderness'.”

We might also note the moment of grief that Inanna experiences before her transition into womanhood, and draw a parallel with Demeter's grief before her reunion with her daughter at Eleusis: in Inanna's case, the joyful (re)union following the grief takes place not with a daughter or mother, but with her prospective husband Dumuzi, in whose beauty and courtship Inanna takes considerable delight. A second moment of union also occurs in the Underworld later on, when Inanna is reborn from the birth pangs of her sister Ereshkigal, transforming the inter-relationship of both.

There can thus perhaps be drawn a tentative schematic of the mythical transition from girl to womanhood in these two female-oriented tales from Uruk and Eleusis: a girl in a primordial or wild locale delights innocently in the expectant beauties of nature before being sharply seized by the suddenness of events. In Persephone's case this is by a narcotic ecstasy symbolised in her kidnap and removal from the world by Hades-Dionysos, while Inanna is confronted by her unacknowledged fears embodied in the serpent, the anzu bird and Lilith. There then follows a profound and lengthy period of grief before help is sought in the person of the Helpful Guide who plays no further part in the story and does not partake in the culminating moment of union: Persephone with Demeter, and Inanna with Dumuzi.

This mytheme is relatively rare in the traditions that have come down to us: Eleusis and Inanna are notable in that they are unambiguous examples. Its diametric opposite, the woman or transmuted goddess as Helpful Guide (called by Jungians the 'Sophia' archetype) for a male is ubiquitous as the Anima to heroes like Theseus and Odysseus, but the male figure as Guide has all too often been recast as Hero-Saviour in a patristic attempt to take ownership of what was anciently a female psychic space. The Orpheus-Eurydice image perhaps narrates the first stage in this transformation, in which the man seeks to play the Hero but ultimately fails, but later Greco-Roman and Western literature is filled with examples of success.

Thus, in highlighting this mythic oddity, we uncover yet another layer at Eleusis, once again preserved into the Classical Age from an earlier epoch in which an Immanent Goddess presided not over a battle of the sexes but a ritually balanced and mythically-informed gender complementarity. I can think of no clearer image of this than the selfless services offered by Hermes and Gilgamesh in aiding two uncompromising and world-transcendent goddesses to come to their fullest fruition as Mistresses of their psychic spaces, and once again, from a modern Western patristic perspective, Eleusis turns the world upon its head.

Helene P. Foley, The Homeric Hymn to Demeter: Translation, Commentary and Interpretive Essays, Mythos: The Princeton/Bollingen Series in World Mythology, Princeton University Press, 1994

Robert Graves, The White Goddess, Faber & Faber, 1960

Richard Hunter, Plato's Symposium, Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature, Oxford University Press, 2004

Mary M. Innes, Ovid's Metamorphoses, Penguin Books, 1955

Carl Jung, Psychology of the Unconscious, Dover Publications, 2003

Karl Kerényi, Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, Mythos: The Princeton/Bollingen Series in World Mythology, Princeton University Press, 1967

Karl Kerényi, Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, Mythos: The Princeton/Bollingen Series in World Mythology, Princeton University Press, 1976

Diane Wolkstein & Samuel Noah Kramer, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth – Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, Harper & Row, 1983

RSS Feed

RSS Feed