However, what is perhaps less considered are the costs, most notably the reproductive costs to hominid females and the upper limit encephalization places on in utero brain development in the context of the width of the female pelvis. As brain size increased, the amount of time that it took to raise an infant to maturity lengthened as there was only a finite-sized aperture through which to be born, and to have altered the physiology of the female hips would have detrimentally altered the balance required to maintain an upright walking stance. Thus, much of the brain development which in apes and earlier hominids would have occurred in the womb now began to take place in the first few years of life. Knight, Power & Watts narrate some of the implications this phenomenon would have had:

“The extra costs arising from encephalization include the metabolic demands on the mother for sustaining brain growth in the infant... and the increased energetic requirements of foraging for a higher quality diet... Because [hominid] mothers bore these escalating costs, we must suppose that it was females who developed strategies to meet them. As maternal energy budgets came under strain, natural selection would have acted on... features of the reproductive cycle.”

The most notable change would have been the progressive suppression of the human female oestrus, whose function in other primates is to advertise the female's fertility, and the concurrent amplification of a misleading signal related to, but not signifying, fertility: that of menstruation which signals the approximate imminence of oestrus rather than its actuality. This startling change in signalling behaviour, which seems profoundly odd from a primate perspective, would likely have facilitated, or perhaps evolved in combination with, the process of encephalization. The reasons for its emergence are subtle and relate to male investment in childrearing, a behaviour largely absent in chimpanzees. This would have advantageously reduced the spiralling costs to hominid females, as Knight, Power & Watts elucidate:

“To drive up male investment, females needed to counter male philandering strategies... The human female appears ‘well-designed’ to waste the time of philanderers by withholding accurate information about her true fertility state. Concealment of ovulation and loss of oestrus... eliminated any reliable cue by which to judge whether a female is likely to have been impregnated...”

Males would thus have been forced to engage in lengthy courtships without ever knowing if or when the female was fertile, and while this would increase the costs to males, it would also permit confidence in their paternity. Menstruation thus becomes a useful, if confusing, signal only to males who attend females for longer periods of time. From this, a 'virtuous circle' of behaviour could theoretically emerge: greater confidence in paternity would lead to greater parental investment. However, it could be argued that once the male was sure the female was impregnated, and this could be ascertained through evidential signs of pregnancy, he might consider his job done and move elsewhere. The female would still bear the vast majority of the reproductive costs and this fragile system would be broken by the philandering behaviour of the cheating males.

We can already see a kind of struggle for investment and energy here between the genders in this behaviour: the reproductive strategies of males and females remained markedly different, and the female attraction towards males showing less philandering behaviours could have easily been subverted by cheating males using their intelligence to deceive the females. Females in turn would have utilised greater discernment in seeking out males, and thus, this dynamic would have driven an evolution towards greater intelligence, and increased the rate of encephalization, exacerbating the initial problem. At this stage, individual and egotistic drives remain the dominant paradigm here, but the dichotomy was to be broken with the next innovation in female behaviour.

Goodall reports that chimpanzee females often group together in male-independent, kin-aligned coalitions to share the burden of child-rearing, and it is likely similar coalitions would have existed among archaic Homo sapiens. This collective behaviour may itself have confused some philandering males, but it also presented the females with another technique to modify male behaviour in response to encephalization costs: that of reproductive synchrony, probably linked to environmental clues initially but eventually to the lunar cycle. Knight, Power & Watts elucidate the advantages of this synchrony:

“If females synchronize their fertile moments, no single male can cope with guarding and impregnating any group of females. Local, previously excluded males are attracted into groups by potentially fertile females... More males become available to the synchronizing females...”

and thus, faced with a coalition of synchronized females whose dominant signalling is oriented towards the imminence rather than the presence of fertility, philandering males lose control of the whole situation while males who are more likely to invest parental time are welcomed into the group, thus increasing their likelihood of being able to father a child for another time. The female collective thus begins to 'police' the access that males have to females, and could even begin to fake signals to ensure continued male presence, such as a non-menstruating female 'borrowing' the menses of her sisters in order to maintain the investment of the males. Here, then, we have the glimmers of the beginnings of a symbolic culture: menstruation as a collective deceit to modify and manipulate male behaviour.

However, again, we find that this is another fragile system that may be cheated, this time by a female who, as it so happens, is not synchronous with the group and who might seek out a philandering male independently of the collective, thus guaranteeing her child genes from an outgroup which may be advantageous. Any independently-cycling female will also stand out to any observant males within the collective, and her individual signal of menstruation thus becomes a powerful method of gaining multiple male investment in her time. This cheating female thus becomes a threat to the incipient collective, and it is in response to this threat that the first decisive movement to symbolic culture occurred, embodied in what has been termed the 'sham menstruation'. Power & Aiello explain:

“...we would expect [all] females within kin coalitions to manufacture synchrony of signals whenever a member was actually menstruating... We might then expect them to resort to cosmetic means — blood-coloured pigments that could be used in body-painting — to augment their “sham” displays... Such coordinated body-painting at menstruation would function as advertising for extra male attention. Provided females maintained solidarity within their menstrual coalitions, even if males were aware of which females were actually menstruating, they would not be able to use the information.”

In other words, the policing of male access to menstruating females, the confusion of signals with red ochre or other pigments and the collective bonds between females would have rendered even a true insight into who was really menstruating worthless, for the females would surely expel any male who attended too closely the genuine menstruants. We have here, then, proto-symbolic behaviour, a collective deception staged by a female coalition intent on maintaining continued male investment in parental concerns. This situation is near-unbreakable, simply because it is not worth cheating: the risks are too high. However, it is not true symbolism quite yet, though as Power & Aiello continue, by amplifying the 'sham menstruation' signals even further through regularity, archaic Homo sapiens females led themselves into an imaginary construct that was collectively-held and indefinitely-maintained, true symbolism:

“So long as female deceptive displays remained... constrained by the local incidence of biological menstruation, they would not be fully symbolic but tied to here-and-now contexts. Symbolic cultural evolution would take off when cosmetic displays involving use of pigment and body painting were staged as a default, a matter of monthly, habitual performance, irrespective of whether any local female was actually menstruating. Once such regularity had been established, women would effectively have created a communal construct of 'Fertility' or 'Blood'... no longer dependent on its perceptible counterpart. Ritual body-painting within groups would repeatedly create, sustain, and recreate this morally authoritative construct.”

Thus the alignment of reproductive synchrony with the regular phases of the moon allowed pre-symbolic archaic humans to move into an incipient symbolistic cultural state that bore a wide range of advantages for the practitioners. For example, sham menstruation displays could also have been used in areas of intense foraging, to variously encourage and mobilise males to engage in the gathering of food. The red painted female figure thus became a moral figure, informing an emerging collective percept, an incipient sacred rule, that males should be helpful and not philandering, and in so doing, created the social environment which led our species from cognitively-archaic hominids to cognitively-modern humans. The monthly ‘sham menstruation’ discloses a non-functional import, a ritual wholly divorced from any real-world referent, opening up an imaginary world in which incipient constructs such as 'blood', 'fertility' and 'moral force' were expressed symbolically through pigment and display.

We might postulate that the cognitive capacity to visualise this new reality may have then engendered yet further encephalization processes – it is known that many of the symbolic cognitions in question appear to have their neurological foundations in the most recently-evolved frontal and pre-frontal cortices of the brain – and the spiralling costs would have created the conditions whereby even increased male attention could not meet the energy needs of the females and their children. Knight and Power & Aiello theorise that it may have then become necessary to utilise this new-found moral force to motivate the males to do something rather paradoxical in this context: leave the female collective to hunt, thereby procuring food from a wider area or to kill animals for high-quality and energy-rich meat.

This was a high-risk strategy, since in their banishment the males may have abandoned their female kin and resumed their philandering behaviour with unrelated groups, but if we assume symbolism was adaptive, we can expect many early cognitively-modern human groups to have exhibited similar behaviours and thus female collectives that were not their kin would have generally been closed to them. Perhaps ironically, with an expanded cognitive capacity due to their incipient symbolism, the males may now have gained as a by-product an enhanced ability to conceive of effective hunt strategies or predict animal behaviour, and the dynamic existing between menstrual blood and red ochre in the sham menstruation ritual may have easily conflated with the blood of the hunt, binding them in an emerging web of symbolic associations.

The females also likely compounded this associative web through a mixture of moral obligation and reward by staging a 'sex strike', in which as Kohn explains:

“...women's displays, loud and vivid and emphatic, inverted the normal messages of [animal] sexual assent. To confirm the possibility of mating, an animal needs to verify that the potential mate is of the right sex and species and that the time is right for fertile sex. The message of the women's ritual was 'wrong sex / wrong species / wrong time'; or, in a word, 'No!' They were refusing sex collectively unless men went out to hunt and returned with provisions.”

Here, male behaviour is manipulated a further time, and Knight, Power & Watts surmise that the 'sex strike' may have arisen during a period of particularly high 'resource stress', perhaps caused by the re-establishment of an ice age some 160,000 years ago. Knight also notes an important implication of the strike for dynamics of autonomy and self-image among the emerging symbolic females:

“This [the 'sex strike'] was the way for females to demonstrate that their bodies now belonged to themselves. Just as the females in effect must have sexually boycotted the defeated Tyrant [an image of the philandering male which Knight uses here], so they would again have had to go on sex strike given any future signs of dominance-like [or philandering] behaviour in any of the males who were now allied to them... More precisely: any male who approached seeking sex without first joining his comrades in the hunt would have had to be met with refusal. No meat: no sex.”

The earliest developmental characteristic of this strike was likely to be wrong time – 'no sex now: go hunting' – but as the adaptive advantage of this spread across human populations in early Middle Stone Age Africa, the red-covered female coalitions began to develop into displays whereby the females became male ('wrong gender'), or the application of the symbolic menstrual blood of the hunt on their bodies conferred animal characteristics ('wrong species') upon them. An important point is that none of these signals – maleness, animal attributes, infertility – would have been visually evident in the immediate context: the displaying females were still obviously female, but selective pressures would have caused visual evidence, as it were, the artefacts of this world, to be subordinate to the much more authoritative symbolic evidence of an emerging unseen world. Indeed, Power’s summary of the model makes explicit the link between these menstrual signals and the incipient perception of deity:

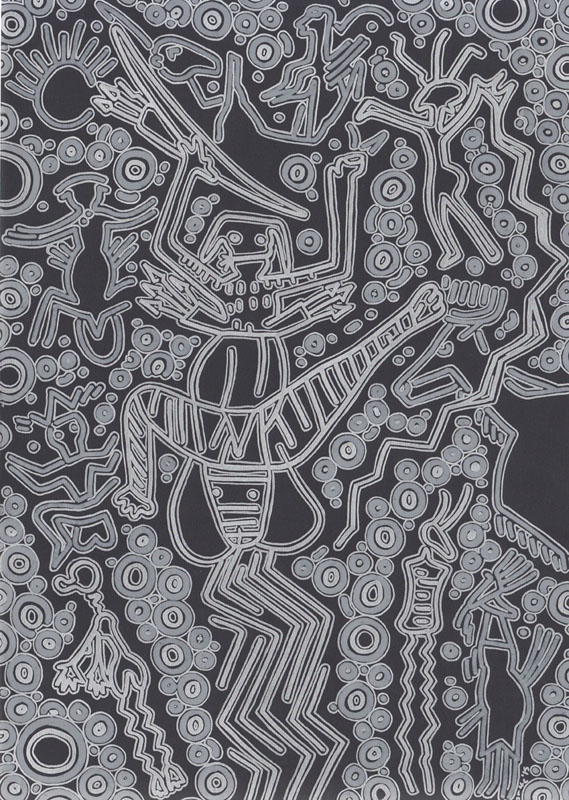

“Because menstruation was valuable for extracting mating effort from males, non-cycling females ‘cheated’ by joining in with menstruating relatives, painting up with blood or blood substitutes to signal ‘imminent fertility’… Simultaneous with advertising fertility using cosmetics, late archaic/early modern females constructed taboos indicating refusal of sexual access except on condition of successful hunting. These involved signalling ‘we are the wrong sex and the wrong species’ in costly ritual performance to deter advances of non-cooperative males. Such ritual metamorphosis into gender-ambivalent therianthropes, highlighted by amplified bloodflow, constituted humanity’s first ‘gods’.”

The cognitive door was thus unlocked to reveal a variety of new social realities, including ideas of the sacred, that were understood according to non-perceptibly verifiable ideas which nonetheless had significant behavioural effects, and most elegantly, these symbols and their effects emerge easily from a Darwinian explication of the implications for encephalization coupled with what we observe for the sexual signalling behaviour of modern human females today.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed