This evolutionary picture, pioneered by Chris Knight and expanded with Camilla Power and several others, of cognitively-transforming humans gaining collective and symbolic identity is a subtle and reasoned narrative that emerges from strictly Darwinian sexual selective pressures, but which nonetheless maintains a lively sense of the sacred throughout. In case the semi-mythical nature of the model should cause one to think it fantasy, however, it should be noted that this 'Female Cosmetic Coalitions' hypothesis, bears significant predictive power upon the fields of archaeology as pertaining to the Middle Stone Age in Africa and possibly Europe, as well as upon the ethnography of modern hunter-gatherer populations the world over.

This model also offers powerful prediction for the increased use of red ochre pigments to emerge in the Middle Stone Age in Africa, a usage which Watts argues has no known nutritional or functional basis. Knight, Power & Watts predict that some time around or immediately following the penultimate glaciation period around 160,000 years before the present, visible evidence of this should begin to show a marked increase in the archaeology, reflecting the employment of the pigment as an artificial body paint for sham menstruation and sex strike rituals:

“We have proposed that…red pigments should be the focus of the earliest symbolic tradition. The ochre record should document an initial period of sporadic ochre use (‘sham menstruation’ prompted only by the local incidence of real menstruation) followed by an explosion in such use (reflecting regularly monthly body-painting…)”

We should also expect to see exclusive use of red ochre despite the availability of other pigments, such as yellow ochre and charcoal. Knight, Power & Watts as well as Volman find all of this to be the case: in a survey of Middle Stone Age sites south of the Limpopo river in southern Africa, including the famous sites at Blombos, Rose Cottage and Cave 13B in South Africa, and Apollo 11 Cave in Namibia, there appears to be little in the way of evidence of red ochre usage before 200,000 years ago, followed by fragmentary evidence of usage beginning around 164,000 years ago (with localised heavy usage found at two sites) then developing into red ochre becoming an important part of the lithic assemblage recovered from sites dating to 130,000 years ago and afterwards.

Bar-Yosef Mayer & Vandermeersch review evidence of red-ochre-stained skeletons and pierced shell-beads from Qafzeh and Skhul in Israel dating to approximately 100,000 years ago, suggesting that by this time, this symbolic phenomenon was adaptive enough to spread through most of the human populations of Africa and into Eurasia coinciding with migrations of anatomically-modern humans. Indeed, these migrations may well have been triggered by the success of these new innovations in social culture and the resultant need to find new territories to support the expanding number of cognitively-modern humans making use of this incipient symbolic complex. Since the red ochre at Qafzeh is now associated with burial and death, this adds another interesting symbolic dimension to the ritual signal: 'wrong time, wrong gender, wrong species… not alive'.

Here again we begin to taste the idea of an incipient religious expression emerging from a developing symbol system: the ochre-covered woman associated with menstrual blood and the blood of the animal hunt now becomes associated with the blood of death, and an otherworldly transition begins to be made. As Grahn has noted, in the symbolic context under discussion, all blood is menstrual blood, and by becoming 'not alive', the red-painted female acquires a magical identity in an association with the blood-borne death of the hunt, an image amplified by the 'sex strike' purposive nature of the hunt itself.

Beyond archaeology, the 'Female Cosmetics Coalitions' model should also manifest itself in highly specific ethnographic features in modern hunter-gatherer cultures, and quite possibly upon later Neolithic cultures also. Some of these can be listed, for example the ubiquity of bride service towards a woman's family before marriage can take place, and early kinship systems being reckoned through the female line with only a weak focus upon fatherhood.

We should also expect a timing of hunt expeditions to be aligned with the phases of the moon, and indeed a taboo on hunting during the few days around the new moon is a common feature in many cultures which is often ascribed to the inability to hunt in total darkness. However, this interpretation fails rather if the taboo is also present during the day time, which for the San peoples of Southern Africa and the Hadza in Tanzania, it is.

There should also be a general rule of sexual abstinence before the commencement of a major hunt expedition, and a taboo on eating freshly-killed meat, due to a cultural raw/cooked distinction, thus regulating the men's appetites through a ritually-sanctioned requirement that 'wild' meat be 'tamed' by giving it to the women to be cooked and thus socialised, by which is understood, removed of the blood-borne dangers of the wilderness. Such dangers may take the form of a belief in vengeful animal spirits who will attack any hunter who transgresses these rules.

Vinnicombe tells that among the /Xam, a San people formerly of the Drakensberg mountains in South Africa, it was documented that among the extremely intricate rules that a hunter had to follow was the rule that, if he should hunt and successfully kill an eland, he may not consume any part of the meat, lest /Kaggen should follow the hunter's trail back home and taunt him in the night. There were also strict rituals to be followed to placate both the deity and the dead eland's soul, as told by the /Xam groups of Lesotho:

“Kaggen [sic], after punishing the son who killed his first eland, told him that he had to try to undo the mischief he had done. [There was] further related how a legendary chief, Qwantciqutshaa, killed an eland and purified himself and his wife. Qwantciqutshaa then told his wife to grind canna herbs... on the ground, and all the elands that had died came back alive again...”

Reichel-Dolmatoff's work among the Desana of the Colombian Amazon also resonates with the various facets of this predicted general rule above, and reports on the beliefs about deer and tapir that:

“...game animals are, in all aspects, female... and only those that have been transformed from strange forest creatures... into true people... can safely be... brought into one's tribe. Only the dark deer of the forest are viewed as dangerous estrous [sic] females and must be avoided. Native attitudes towards deer are highly ambivalent... deer are seen as clean, sleek forest maidens... on the other hand they are repulsive bitches in heat. Both tapirs and deer feed on forest products and not what people grow in their fields... there is a very definite 'otherness' about them... they belong to another dimension.”

Even the Desana word for deer, nyamá, relates to several words with both transformative and sexual connotations and the killing of a deer is often likened to the selection of a marital partner. Elsewhere he reports upon the preparations that the hunter must undergo before embarking on a hunt, which strongly relate to Vai Mahsë, the Master of Animals to whom all animals of the forest are subject:

“In order to obtain the Supernatural Master's permission to kill a game animal, the prospective hunter must undergo a rigorous preparation which consists of sexual continence, food restrictions and purification rites ensuring the cleansing of the body...For some days... the man should refrain from all sexual relations and... he should not have had any dreams with erotic content. Moreover, it is necessary that none of the women who live in his household is menstruating.”

The Desana generally consider women to have a pleasant odour, but not when menstruating, and Reichel-Dolmatoff elucidates the meaning of this olfactory change:

“Menstruation means that she has passed from her normal, human state to an abnormal one that links her to the beasts of the forest, and in this lies a great danger... to all men, to herself, her offspring and also to the game animals. Her state affects the very essence of nature's fertility and introduces a serious conflict into all man-animal relationships...”

Levi-Strauss reports that among the Tupari, the odour of a menstruating woman is believed to cause migraines in her male partner, a phenomenon demonstrating a link between the associations under discussion and visionary experience, and the apparent ubiquity of negative effects of menstrual odours among human populations may have a Darwinian function with respect to the ‘sex-strike’ image we have discussed. Scent also participates in the nexus of symbols surrounding menstrual seclusion rites, as we shall see.

In his anthropological fieldwork among the Mbendjele Pygmies of Northern Congo, Lewis showed that menstrual odours are said to anger large or dangerous animals such as gorillas, buffalo, leopards and elephants, causing them to attack anyone who smells of it. This belief is further elaborated into a system of taboos that defines sexual division of labour and proper sharing practices. This system is called ekila, a word which can refer to menstruation, blood, a hunter’s meat or the power of an animal, and as such it is a concept which neatly reproduces in microcosm much of the model under discussion.

Equally, however, the magical power of a menstruating woman's odour can have positive effects, as Reichel-Dolmatoff continues among the Desana:

“The Desana say that because of feral estrous [sic] odours, women will attract game from far away, and hunters might profit from this. Menstruating women often claim to have erotic dreams involving... animals, and in these cases, a man might take his wife along on a hunting excursion to serve as bait, because the animals will approach without fear.”

Cooking is also a very important ritual process among the Desana and a key concept for them in this regard is bogë, ripeness, a term linked to both menstruation and socialised food. All food must be transformed through cooking into bogë before it is safe to eat, and raw or roasted meats are generally shunned in favour of smoked preparations. Reichel-Dolmatoff also explores the nexus of associations between the female body and the cooking pot, noting among many other aspects, that female body painting and cooking pot decoration closely mirror each other.

In this complex of symbolism fire and cooking thus become artefacts of female control, power and of purification, indeed the process of cooking emphasises menstrual signals, since it removes blood from meat and thus permits male familiarity with it to be minimised. At length, the fire itself can become conceived as female. Among the Ainu, the hearth occupies the central position in a dwelling and is the embodiment of Fuchi, the kamuy or spirit of the fire, who presides over and protects the occupants as the most powerful deity in the pantheon. This hearth is the central focus in the famous bear-sending ritual in which a bear-cub is kept alive in the house for a year before being killed. During this time, the Ainu consider that the bear as 'the spirit of the mountains' (by which is meant, wilderness) is conversing at length with Fuchi as the embodiment of human sociality.

Shamanic practices also take place near the fire, and as such Fuchi acts as the mediator between the gods and the shaman, who are usually women. Ohnuki-Tierney elucidates the symbolic associations this siting has for the Ainu:

“...several aspects of shamanism reveal the importance of the female principle in Ainu culture: the rite is held in the woman's domain, inside the house and most importantly beside the hearth where Fuchi resides... It is here that women prepare the daily meals... In other words, shamanism is expressive of the act of cooking, the conversion of raw natural products into culturally acceptable food, and it also involves healing, the way humans prevent a person from returning to nature through death.”

Thus a symbolic association between menstruation, the blood of the hunt, fire, and raw/cooked distinctions as well as magical powers of various forms can be made which confirm the ubiquity of some of the aspects of the 'Female Cosmetics Coalitions' model. Indeed, fire may have been one of the earliest initiators of the whole process under discussion, since Kohn explains that during the first period of encephalization taking place among Homo ergaster populations some two million years ago, much of the energy costs may have been met by shrinking the gut, reducing the overall efficiency of the digestive system. We might thus suggest that fire permitted an ability to pre-digest food before it was consumed, a useful innovation which cooked and softened food, helping to meet the rising energy costs of the expanding brain. This is generally what is seen in the archaeological record, with the earliest evidences for fire usage coming in throughout the first period of encephalization. Gathering around a fire in the cold of a Eurasian winter or African night would thus have been a convenient locale from which further coalitionary behaviour might develop.

Another prediction of this model would be the suppression of competitive urges among hunter-gatherers, these drives being equated with philandering behaviours particularly among men, and there might also be a taboo against boasting. In connection with a discussion about the Hadza people of Tanzania, Knight says:

“Hunter-gatherers can be as competitive as anyone, but they are under pressure to compete in a paradoxical way. The struggle is to be perceived as non-competitive – and the best way to succeed in this is to be genuinely so. Esteem and corresponding status in a hunter-gatherer band goes not to the most dominant or assertive but to those best at establishing... [their] ability to join with others in transcending internal conflict, displaying generosity and suppressing attempts at dominance by selfish individuals.”

Indeed it could be argued that these ideals of human behaviour are found ubiquitously in some form or another across human society, encoded variously as codes of practice or immutable moral laws, albeit ones whose limitations are not always adhered to. Once again, the menstrual perspective on the origins of culture liberates quite naturally a moral code of behaviour not imposed from outside or from magical thinking, but as an essential, internally-consistent emergent feature.

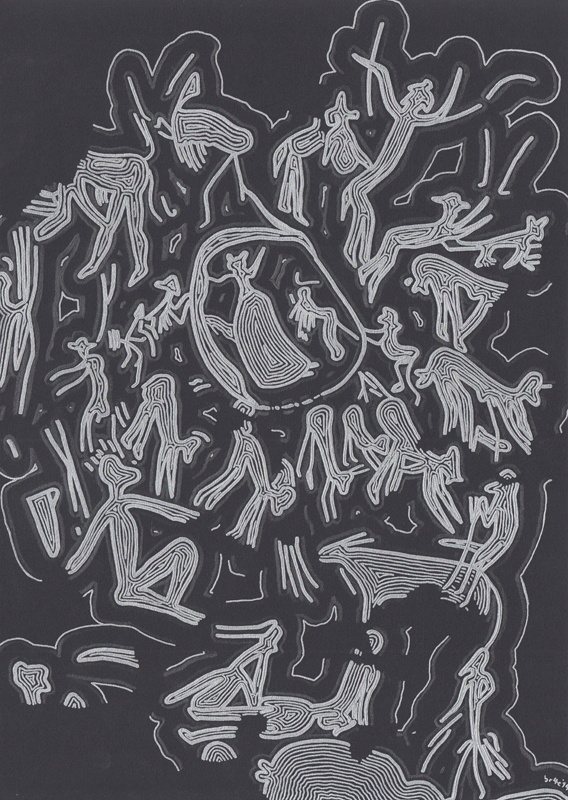

We should also expect to see this model reflected in the earliest artforms of our species. It should be assumed that the first canvas for art was not the rock wall but the human body, with red ochre and later decorations such as perforated beads, the latter of which is found in the archaeological record from about 80,000 years ago from sites such as Blombos in South Africa and Taforalt in Morocco, amplifying the menstrual signals to indicate the unseen and symbolic world. At length, the drive to reify these constructs ever further would have caused early cognitively-modern humans to begin re-creating them in static visual form, an innovation which would have fossilised the import of the menstrual rituals, previously at their most powerful when actually being performed, into permanent form. These static forms would have required great effort, emphasising the ‘expensive ritual’ aspects of the model we are discussing.

We should expect early artforms to suggest the manifestation of the paradigm 'wrong time, wrong gender, wrong species… not alive', and indeed this is what we observe among the San peoples of Southern Africa, who until very recently maintained markedly similar hunter-gatherer lifestyles to those theorised for the Middle Stone Age, and in the same approximate region theorised as the urheimat for the symbolic practices here discussed. San ritual and rock art traditions are very ancient indeed: some images in the Drakensberg may possibly go back 25,000 years while in places such as Tsodilo in the Okavango Delta in Botswana, there is evidence for ritual behaviour beginning 70,000 years before the present.

Therianthromorphic females are particularly visible in this tradition, disclosing the 'wrong species' aspect of our model, and often shown in the context of menstrual rites. Van der Post & Taylor narrate the meanings behind a remarkable petroglyphic artwork at Fulton's Rock in the Drakensberg mountains of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. The rock surface, which is painted in purely red ochre tones, is somewhat damaged, but the image of at least two concentric circles of dancers surrounding a central covered figure is nonetheless clearly visible. They follow Lewis-Williams in reporting that it depicts a girl's first menstrual ritual:

“[Lewis-Williams] believes that the covered figure inside the incomplete circle is in fact a girl isolated inside a hut for the duration of her first menstruation, with one or two women to keep her company; that the female figures surrounding the hut and bending forward are women performing the ritual dance, and imitating the mating behaviour of female antelopes; and that the other figures (some definitely male, others probably so) represent the few men that join in the dance, some holding sticks which represent an antelope's horns...”

The girl in the hut and some of the antelope dancers also have heads whose shapes are deformed into forms reminiscent of an animal, perhaps an antelope or perhaps an eland, which is also seen at the base of the frieze. Van der Post & Taylor consider this animal's presence to be significant:

“Among the !Kung the dance that is performed around the hut in which the girl is isolated is the Eland Bull Dance, and it is fascinating to see... the shadowy figure of an eland... a symbol of the supernatural potency (n/um) that the girl is believed to have at this time... it is the source of the most powerful n/um...”

The Eland Bull Dance, which is justly famous, throws powerful light upon this petroglyph, but also, to a certain extent on the whole model. That the women dancing around the hut conceive of the new menstruant in the hut as symbolically male – 'wrong gender, wrong species' – is suggested by the movements of the dance itself, imitating the mating dances of the female antelopes in seeking a mate during the breeding season. The connection between the menstruant and n/um, immanent supernatural power, a quality which is also possessed by powerful shamans among the San people, makes explicit the connection between this image and the visionary abilities engendered by trance-based activities such as dancing.

The petroglyph seems to depict precisely what Knight, Power & Watts have been postulating: a female collective who surround a new menstruant to cover her in both ochre and symbolic associations, and who then amplify these associations with a ritual display in which all the customary signals of animal sexual behaviours are inverted. The presence of a small number of men here perhaps reflects non-philandering male kin who are also essential aspects of the model and of the emerging proto-symbolic cosmetic coalition.

Eland-headed figures also feature, as reported by Vinnicombe, in several hunting scenes at Soai's Shelter and other sites in the Underberg district in the Drakensberg. They appear cloaked, or partially occluded by a dead eland and in some respects appear to preside over the hunting action of the scene. In light of what we know, it might not necessarily be speculation to interpret these figures as female. Bleeding from the nose in San rock art of the Drakensburg consistently appears to denote an altered state of consciousness, and thus the resonance of the unseen with blood is again apparent.

Early artistic attempts to reify the magical world beyond the menstrual rituals through the creation of artistic imagery would have also caused, perhaps inadvertently, another innovation, one which needs little discussion to demonstrate its ubiquity among modern humans. The incipient magical power invisibly evident within these artforms would then have begun to transfer to the locales in which they were painted, liberating the concept of the sacred site. The adage “art makes the world sacred” seems particularly appropriate here.

Another important ethnographic prediction is the power of the menstruant, and especially the new menstruant to destroy the world, which from the perspective of the 'Female Cosmetic Coalitions' model represents the potential threat that a non-synchronous or cheating female presents to the emerging collective identity by encouraging competitive and philandering male behaviour, leading to the extinction of the power and thus the meaning of the menstrual symbolic signals. Grahn provides a neat review of some of the relevant aspects of menstrual seclusion rites, in which the new menstruant is ritually separated from the world by some means in order to prevent this situation from arising, and quotes an ethnographic example from the Tiwi people of Melville Island:

“During her first menstrual period, the [menstruant] is removed from the general camp and makes a new camp in the bush with a number of other women... includ[ing] her mother... No men are allowed in this camp... She cannot touch any water... for otherwise she would fall ill... She cannot look at bodies of salt or fresh water, for the maritji [spirits] might be angered and come and kill her... These taboos and several others... include not going near small bodies of water, lest they dry up. She must not take long trips over salt water or the maritji will blow up a storm.”

Power & Watts report a similar belief among the /Xam, in which the menstruant’s odour participates in the taboo against her coming into contact with water:

“The /Xam distinguished between the desired, gentle 'female' rain, which fell softly, and the destructive 'male' rain… The danger lay in the maiden's capacity to summon and unleash this 'male' power. Violation of menarcheal observances roused the wrath of the being !Khwa, manifested as a whirlwind, black pebbles, lightning or Rain Bull… /Xam informants emphasized that !Khwa was attracted by 'the odour of the girl'.”

They also note that the word !khwa could refer to both menses and water, and that she herself was referred to as //kaan, a word meaning variously ‘maiden’, ‘rain’ and ‘raw, uncooked’.

We see here how the menstruant's power to break the collective and the symbolic world is constrained by her seclusion with close female kin, who surround her with strict taboos about water, for in this magical and threatening state she has the power to cause essential water sources to disappear or storms to be called. Grahn also quotes a story from the Toba people of South America in which a woman was menstruating, but her female kin did not leave water for her to drink, so she went down to the lake to drink, whereupon it rained until all the people were drowned.

We see vestiges of these practices in the superstitious attitudes that many Occidental religions have towards menstruating women, albeit inverted in a male-dominant modern social context to an 'impure' rather than 'sacred' category. Grahn even quotes a common attitude among young women of the American 1950s – “don't go swimming or get wet when you have your period” – and the Toba tale bears considerable resemblance to the Yolngu story of the Wagilag Sisters, from Arnhem Land in northern Australia, and the presence of similar flood/destruction menstrual images in myths from so widely-divergent peoples across the world provides strong evidence for the model we are discussing.

Caruana & Lendon relate how two sisters are fleeing across the landscape of the Upper Woolen River, pursued by clansmen for some unspecified transgression, when they chance upon a waterhole. In their version, both sisters are pregnant but variants exist in which only one of the women is heavily pregnant and the other is menstruating:

“...one of the Sisters pollutes the waterhole, which arouses Wititj [the Olive Python] from his sleep. The younger Sister gives birth, further inciting the snake. Unsuspecting, the Sisters make camp, build a bark hut and try to cook the food they have caught, but things begin to go wrong – the animals and vegetables come to life and leap into the waterhole. Wititj emerges from the waterhole and creates a storm cloud with lightning and thunder... Frightened, the Sisters perform dances and sing sacred songs to deter the Python. Finally, the Sisters drop in exhaustion and Wititj is able to enter their hut and swallow them...”

Cowan narrates a variant of this story among the Yirrkala, in which the nature of the ‘pollution’ is powerfully elucidated. Here, it is only the elder sister who is pregnant, and she gives birth at the lakeside, and it is her post-partum bleeding which finds its way into the waters, arousing the serpent whose name is Julunggul in Yirrkala lore. The younger sister begins to frantically dance to placate the rising Julunggul, her exertions being energetic enough to cause her to begin menstruating, and these also find their way into the pool.

A remarkable nexus of relevant associations are visible here: the equation between menstrual flow and fertility is made apparent, and the women dancing before a chaotic male figure who is attracted by their blood emissions has bearing upon our image of the menstrual coalition’s displays to modify philandering (read: symbol-destroying) male behaviour. Knight also narrates how the Rainbow Snake (that is to say, Wititj and Julunggul) represents a post-Palaeolithic male intrusion into, and appropriation of, the symbolic complex surrounding menstrual signalling, and something of this tension between genders is visible in this story.

Van der Post & Taylor also document a menarcheal rite among the !Xo people of the Kalahari. The moment that the newly-menstrual girl realises she is bleeding, she informs a friend or relative and then stays in the very spot where the realisation was made while the friend dashes back to the rest of the tribe to initiate preparations. A hut is hastily constructed and two karosses are set aside, one of which will be given to the girl for her journey to the hut, and the second for her to sit upon once arrived. They narrate:

“With a whoop of joy, [the new menstruant] !Kaekukhwe's mother, /Kunago, leapt to her feet and ran to where her daughter was sitting... Her mother bent down and took her daughter onto her back, while another woman covered her with the kaross so that even her face was lost to sight. Then she was carried back to the hut...”

As with other peoples, an array of taboos surrounds this emerging young woman lest she inadvertently cause disaster due to the awesome power she now embodies. Her condition inside the hut resembles simultaneously primordial nature of the wilderness outside socialised society and the child reborn from a symbolic womb:

“During the whole time of her menstruation the girl must not touch the earth, neither must sun fall upon her. She must wear no beads or clothes. Food is brought to her inside the hut where she remains alone for most of the time... No man may see her face for it is believed ill-luck will befall him... Every day the women dance around the hut, and on some occasions two or three of the older men join in...”

Van der Post & Taylor were surprised to learn that this particular dance was called the 'Gemsbok Dance' rather than the Eland Bull Dance but beyond the detail of the name, it appeared little different from the corresponding rite among the !Kung. He also noted that some of the most provocative movements from the women, which imitated most precisely the movements of the gemsbok, took place directly in front of the hut's entrance, within the sight of the menstruant who accordingly now became symbolically transformed into a male figure.

The resonance of the ritual with the rock art from Fulton's Rock a thousand miles south of the Kalahari struck van der Post deeply, and its similar resonance with everything we have been here discussing should, I believe, engender a profound sense of awe at the venerable age of the San peoples' traditions.

There is one final ethnographic example which is remarkable in its distilled encapsulation of the essence of our present discussion, that (to paraphrase Grahn) for cognitively-modern humans menstruation quite literally created the world. Becher narrates a tale from his ethnographic work with the peoples of the Surára and Pakidái people, a subtribe of the group famously known as the Yanomami. An episode from their creation myth bears retelling here:

“The earth already existed but was without people. The first man, Uruhi, came from the leg of the Xiapó bird... Shortly thereafter the bird's leg bore a second man, then a third, a fourth and finally a woman, Petá... Petá was the wife of Uruhi, the first-born... After one year, Petá gave birth to a strong and healthy boy... One night just for fun he aimed at the moon and shot an arrow. Immediately there was an eclipse of the moon and blood dripped down and flooded the entire earth. From this blood originated all the Yanomami...”

Becher reports that much of this blood congregated in a great lake in the sky, at the centre of which is a vagina. This is a powerful image, deeply linked into our complex of Middle Stone Age symbolism of blood, hunting, the new moon as a time of taboo and magic, and the creation of our humanity in a metaphorical sense. In a survey of indigenous South American weather lore, Wilbert interprets and deepens the picture further by explaining that for the Yanomami, there exists a correlation between rain and blood, and a variant to this tale is found in which:

“...the moon continually shakes blood from trees in the sky; it falls to earth in droplets containing human souls, ready to be incarnated through sexual intercourse...”

and that among the Sanemá, another subgroup of the Yanomami, menstruating women are seen as rain clouds, the heaviness of the menstrual blood being equated with the heaviness of rainfall. The clarity of this memory, and the ubiquitous presence of variants like it, continually re-creating different 'drafts' of the Middle Stone Age social reality, is remarkable in light of what we now know about our origins in a menstrually-inspired human symbolic revolution.

Dennett speaks of 'good tricks' that evolutionary processes will employ in order to strive towards maximal advantage. Not without deep insight does Kohn remark that Christopher Knight and his colleagues have constructed here the image of a trick of extraordinary cunning – almost supernatural! – through which archaically-minded Darwinian hominids were able to reconcile their competing interests to such a degree as to invert the majority of their instincts and drives, and come together as a collective which permitted the flowering of language, art, magic and the accelerated insights and advantages of symbolic culture.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed