In addition, future serialisations will be interspersed with stand-alone essays of the type with which this blog was begun: coming in the next few months, a look at mythical images of emergence, the Bird Man of Lascaux and the complex beliefs behind Wandjina rock art figures in Australia

“...survival after death... of the sacred area (sanctuary)... of the efficacy of ritual, of ceremonial decorations, sacrifice and of magic... of supernal agencies...of a transcendent immanent power (mana, wakonda, śakti, etc)... [and] of a relationship between dream and the mythological realm...”

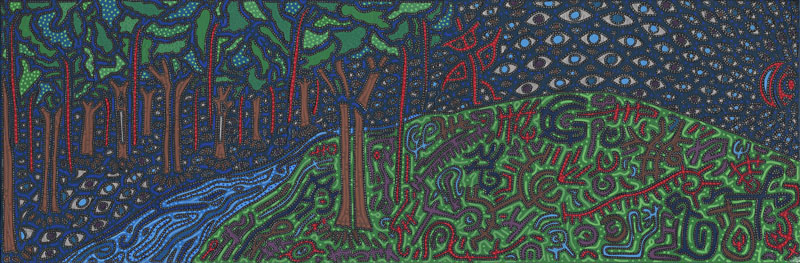

First there are clear boundaries between this world and that, even when simultaneity is occurring to sanctify or otherwise blur the line between sacred and profane. These boundaries are temporal as well as spatial: appropriate seasons or movements of the stars may open up the World-Beyond-Worlds to human perception as much as the initiation of a ritual. Spatial boundaries may be portals in particular locales – rivers, lakes and caves as entrances to an Underworld or world-womb, or the entrance gate to a temple or shrine as symbolic entrance into the Heavens or shimmering image of unity within the world. The edges of wild places, the sacred grove and even a sacred object can be so imbued with magical power that they open up the World-Beyond-Worlds, permitting the shaman or visionary to enter and, in the case of art objects, making it visible even to the mundane viewer.

Or the transition can be one of state, as of the dreamer into sleep, the shaman into trance, the expectant mother into labour or the sick person into death, and while all such phase changes are psychosocially and symbolically conceived, they are to be understood in a ritual manner.

Paradoxically, despite the boundaries delimiting this World-Beyond-Worlds, it is nonetheless conceived as startlingly close, as near 'as the breadth of a human hair' in common Christian terminology, or as the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas states in reference to the Kingdom of the Father:

“It will not come by waiting for it. It will not be a matter of saying 'Here it is' or 'There it is.' Rather, the Kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and men do not see it."

Thus the movement to this other world can be of the form of a long pilgrimage to a sacred space or the simple closing of one's eyes in trance to make the Image visible.

Once arrived however, the language of the journey and the landscape is not one of words or reason, but of images, of dreams, myths and spirits of considerable agency. Simultaneity gives way to mandalas of meaning, delightfully illustrated in this narrative of the !Kung shaman Old K''xau from the San Bushman peoples of the Kalahari which describes the entrance way into the world of spirits:

“Kauha [God] came and took me... We travelled until we came to a wide body of water. It was a river...The two halves of the river lay to either side of us, one to the left and one to the right. Kauha made the waters climb and I lay my body in the direction they were flowing. Then I entered the stream and began to move forward. I entered it...I was stretched out in the water and the spirits were singing... [they] were having a dance...”

Here the image of the river flowing in two directions upon the earth, and then upwards ('Kauha made the waters climb') resonates with near-universal images of the Milky Way as doubly flowing: the river thus becomes imbued with multiple meanings, and by implication spiritual power, as the earthly river seen in the vision has its origin and sacred precedent in the heavens in a manner which recalls Eliade's model of the Eternal Return.

Indeed all sacred precedents are here found, and the Image of this World-Beyond-Worlds shimmers with animism: everything appears imbued with a life-force and consciousness and as the visionary gazes into aspects and apparitions there is a gazing back into the visionary. One sees in a sacred manner, and this life-force spills out into mundane experience, with spirits being found, and indeed acting as the foundation, in every aspect of creation, a kind of living Aristotlean essence immanently present in each object and every creature, which exhibits paradoxical properties of being unique to each individual as well as being collective and interconnected to a wider sacred whole in another and rather abstract example of simultaneity.

Chagnon illustrates beautifully an example of this animism in his description of the hekura spirits among the Yanomami of the Venezuelan and Brazilian Amazon:

“There are hundreds – perhaps thousands – of hekura. They are small, varying in size from a few millimetres to an inch or two for the really large ones. Around the heads of male hekura are glowing halos... Female hekura have glowing wands sticking out of their vaginas. All the hekura are exceptionally beautiful... Most are named after animals, and most came into existence during some mythical episode that transformed an Original Being into both an animal and its hekura counterpart. The hekura are said to be found in the hills or the high trees, often suspended there, but they can also live under rocks or even in the chest of a human...”

Thus they dwell in the same wild or liminal places that function as entrances into the other world, and Chagnon speaks of individual trails leading from the sky, mountains and the edge of the world, which the spirits follow to arrive at the human host's body, attracted there by the shaman's song like a swarm of butterflies hovering over food in the forest.

The landscape of our Classical Image is often dark, occluded or misty – at least at first or to the inexperienced observer setting out upon the journey – and the topography is labyrinthine, dreamlike and ever-changing. At length however, this occlusion gives rise to brilliant light, whether of literally-conceived sunlight or of spiritual or meditative illumination, mirroring the journey from an Underworld of the soul into the heavenly spheres of the highest deities.

A shapeshifting nature abounds: non-material beings and wild spirits like the hekura above seem to represent a bewildering variety of referents, their identities liquidly folding and re-enfolding into each other. Deities become identified with each other and fuse together or the world turns upon its head, as I wrote in discussing the transformations evident in crossing the threshold of the Eleusinian Mysteries:

“[Hermes's] role in the Mysteries is profound, and counter-intuitive: we have already seen how [the Archetypal Image of Life] Dionysos as the Lord of Death turns the world upside down, now we find deathly psychopompic Hermes in the role of bringer of life and light, in that he returns Persephone back to Earth bearing the Divine Child...”

“Sons become fathers and again, in turn, sons. Mothers become daughters, to be reunited in turn as mothers. Demeter becomes Persephone and as she emerges into womanhood, she becomes Demeter, and both are simultaneously Kore.”

The shapeshifting often gives way to a synaesthesia of the senses where sound and vision fuse, or bodily sensation becomes music. Ayahuasca visions are guided in this sphere by the icaros sung by the shaman, some of which do not simply guide or form what is seen but have the capacity to create whole new visionary worlds for the journeying soul to experience. The senses are confounded and re-harmonised into perceiving a greater unity or interconnected wholeness: at Eleusis, the final experience was of a terrifying vision of Thea, Goddess as Visionary Event, whose identity was formed by the fusion of all the goddess images into a Wordless Ineffability into which the participant was utterly subsumed.

As one becomes subsumed into the sacred, whether through ritual or visionary journey, one finds oneself in the heart of the World-Beyond-Worlds, where all actions become exemplary in form and mythical in import and effect. The possibility exists in many traditions of the journeying soul or ritual participant becoming the deities themselves, at first in a ritual re-enactment of the nature of play, but understood more deeply as a transformation of the self as an embodiment of the Image itself.

Morris and Peatfield elucidate something of this idea in a Minoan context in their discussion of the 'enacted epiphany' in Bronze Age Cretan ritual. Here, a human participant – most commonly female – is depicted as acting as the deity, interacting with worshippers, receiving offerings and performing sacred actions 'as if' she is identical with the deity. This 'external action' they consider to be play-acting, but rather than utilising this idea dismissively, they consider its implications:

“Even the most superficial actor is aware, however, of the emotional power of drama, that what you do affects how you feel. The drama is not simple pretence, but a collective participation... This is the 'internal' dimension of action: physical action can be used to affect emotional and psychological states, and to access altered states of consciousness,which transcend everyday realities. In other words: the holistic interaction of body, mind, and spirit creates a conduit to mystical experience.”

And thus it is easy to see how an actor can become a deity, albeit temporarily or in a ritual sense, but this transformation will occur both in the mind of the actor as well as in the experience of the audience. In this regard, one also might call to mind the Nepalese kumari, a young pre-menstrual girl who is worshipped as the manifestation of the divine female energy, devi, or as an avatar of the goddess Durga. Simultaneity occurs here again: we see both the human girl and the goddess as enfolded together, one identified with the other.

The dances of the aboriginal Yolngu people of Arnhem Land, Australia also take on these liquid attributes: the Dreaming, that parallel world of magical and eternal intent is opened up by the dance such that each dancer becomes the primordial creator of the actions danced. The Sanskrit proverb tat tvam asi 'thou art that', you are a manifestation of the sacred and transcendent if you would but see it, is also relevant here.

A sense of unity pervades the Image, of interconnectedness and the realisation, believed with unflinching conviction, that one beholds an Ultimate Reality or gazes into the Infinite Mind of God, partaking of an experience mysterium, tremendum et fascinans (in Otto's terminology) beyond all words, categories or conception, disclosing a marvellous Perfect Truth which renders as mere imperfect shadows all the crude products of nature and of the profane world.

“Terror, anxiety and bewilderment turned to wonder and clarification, darkness into light!” were the words of Plutarch in his Moralia when speaking of the Mysteries, capturing perfectly the awe-inspiring movement beyond fear and delight into boundary-breaking enlightenment. Plotinus, quoted by Caruana, offers a less experiential focus which illuminates in a different way:

“The man who obtains the vision becomes, as it were, another being... Absorbed in the beyond, he is one with it, like a centre co-incident with another centre... [I]t is so very difficult to describe, this vision, for how can we describe as separate from us what seemed, while we were contemplating it, not other than ourselves, but perfect at-oneness with us?”

Here, then, the paradoxical notion of the Sacred Other is purged away, but so also are purged individual identity, language, thought constructs and the symbol before the dazzling light of that which transcends everything, including being and non-being, image and non-image, time and non-time, space and non-space. In this final stage, the World-Beyond-Worlds fuses with and surpasses profane reality and as Eliade states: “...for those who have a religious experience, all nature is capable of revealing itself as cosmic sacrality.”

Thus is the Classical Image of the World-Beyond-Worlds elucidated, and while many of the details and attributes of this Image may perhaps be confined to the experiential spheres of vision and ritual, the basic model of a hidden world has influenced thinkers and philosophers for centuries. We have already seen how Plato's World of Forms mirrors the Image in its rendering of all mundane objects as mere shadows of this higher existence, but we can also see that a different but nonetheless influential relationship is disclosed by Aristotle's essences.

Although Aristotle challenged Plato's otherworldly Forms and relied upon what he considered to be the truth of the senses in this world and as such, did not particularly recognize the distinction between sacred and profane realms, he too sought an immutable bedrock upon which the ever-changing world could be eternally founded. Rather than considering worldly objects to be imperfect copies of ideals from a World-Beyond-Worlds, he considered that the essential nature of those objects could be found inherently within each example. This essence has specific attributes of non-corporeality and control:

“The essential nature (concerning the soul) cannot be corporeal, yet it is also clear that this soul is present in a particular bodily part, and this one of the parts having control over the rest (heart)...”

Aristotle does not deny that universal qualities exist, but simply that their immutable nature is founded within the world rather than externally in a non-material realm. However, it is difficult not to see some resonance between this idea and the animistic notion of a spirit dwelling within each worldly object, exhibiting the same paradoxical properties of individuality and collectivity, and the notion of an essence within all things remains an influential idea to this day. We could perhaps regard the Classical Image as a kind of mythically ecstatic fusion of the otherworldly Forms of Plato and this emphasis on the essence in all things, but ultimately, Aristotle's focus was upon the study of the world made manifest – humanity may best learn through observation rather than meditation – and as such he is commonly cited as a founding father of the sciences whereas Plato's influence is much more clearly seen, albeit without attribution, in the ensuing monotheistic religions of the Occidental civilisations.

In some respects, the Platonic and Aristotlean models were fused, or perhaps broken down, by Maimonides (Moshe ben Maimon), who held that God, being indefinable, has no attributes. He argued that all attributes are either accidental (worldly) or essential (otherworldly), and since God has no accidents (or rather, is not worldly) and essences have the property of defining what they dwell within, the nature of God is wholly unknowable and unattributable. Any consideration of the reality of the ultimate in terms of essence liberates not clarity but meaninglessness:

“When the intellects contemplate God's essence, their apprehension turns into incapacity... However great the exertion of our mind may be to comprehend the Divine Being or any of the ideals, we find a screen and partition between God and us...”

At first glance, this way of thinking seems squarely in the Platonic camp in its separation of an ideal world from this mundane one, but Forms themselves represent attributes and the unknowability of God in Maimonides' terms breaks even this down. We are left here only with the experience of the mysterium, tremendum et fascinans of the final and ecstatic stage of the aforementioned Classical Image.

Another fusion occurred with Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and his idea that the soul and body were distinct entities, arguing that the soul exited the body after death, a notion profoundly resonant with imagery of the shamanic voyage or dream flight. Here, an Aristotlean essence within the human body is posited, but that essence is granted by God (and thus has otherworldly referents) and the Platonic dualism of an Ideal and a mundane, housed simultaneously within the same body is preserved.

And so on, down the centuries, this fusion of Platonic and Aristotlean ideas manifested itself in a variety of different ways and directly inspired the emergence of the scientific method: indeed, for many years the process of scientific discovery itself represented precisely the same fusion in that it posited an unfolding set of laws, or Ideals if you will, that underlay all actions of the world, the understanding of which was gained through worldly study. Thus we see that the dichotomy of this and that presented by the Classical Image of the World-Beyond-Worlds is immanent within all major fields of human understanding – religion, philosophy and science – in some form or another, and Campbell's comments that such a distinction is surely to be founded biologically rather than culturally is remarkably apposite.

Which brings us, at length, to the threshold of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the time period in which all this was undone, and the World-Beyond-Worlds began to unravel. The seeds for this unravelling had in fact been planted many centuries before, in the emerging rejection of the ritual framework of the Eternal Return which began first in the cultural sphere of the Middle East, and among the Jewish people in particular, but rapidly spread across the Occident with the advent of Christianity. Eliade holds that the uncoupling of archetypal experience from a foundation grounded in an eternal Sacred Other and its descent into a linear historical time probably came about from a fusion of native, Mesopotamian ideas with Persian (that is, Zoroastrian) images of the dualistic cosmos that were entering Late Babylonian cultural horizons around the time of the Biblical Exile.

This movement out of myth into history had a variety of implications for Western religious and cultural experience, not least a reckoning of time from the creation of the world making a sense of human progress possible and giving rise to an awareness of the indignity of the human condition along with a rising notion that humans could have rights in urbanised social settings rather than mirror their societies upon the merciless vicissitudes of a deified nature. Just as God began to act upon history in a series of revelatory events, the fusion of historical time with philosophical enquiry eventually gave rise to the sciences and the industrial revolution which permitted humanity to feel it was wresting control of its destiny away from God, the World-Beyond-Worlds and any sense of an immanent sacred.

There was perhaps an uneasy co-existence for a while but the line was drawn in the fifty years or so surrounding the first decade of the twentieth century, at the beginning of which saw the revolutionary publication of Darwin's Origin of Species and culminated with the profoundly counter-intuitive discoveries made in the field of quantum mechanics. Both of these theories formed a watershed for humanity that once crossed could not be un-discovered, and the implications for religious experience and everything that we thought we had previously known – the Classical Image – was challenged and broken.

Our modern world has thus become polarised between faith, represented by those who hold that a literal conception of the Classical Image is possible in some form and reason, being the party of those who wholly reject the Image and the realm of experience that the Image implies has largely been forgotten except by a few on the fringe. These folks realise that humans in general feel an intense, if often unanswered, drive towards the mythical and the sacred regardless of how heretical or unreasonable we are told it may be, and that happy and healthy lives can be lived by exploring those drives.

Any solution to this contemporary antagonism must be able to fuse the mythical with the rational, and with the faithful too, but it cannot do so by retreating back to a time before the line was drawn by Darwin and the quantum physicists. The Classical Image of the World-Beyond-Worlds will thus be challenged, and as we shall see it does not survive these challenges intact, while the wisdoms of Plato and Aristotle which have comforted and illuminated us for millennia will need to be discarded. But in doing so, we should not lose the lively sense of the sacred – even if only metaphorically or symbolically held – we have here cultivated as we proceed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed