Scientific theories are at heart models, and thus this symbolic cognitive component must be recognised in some way. We have seen that elementary particles have no fundamental 'objective' nature: it is not that such a nature is unobservable or hidden but that it is absent and irrelevant to an accurate description of quantum systems, an idea neatly summarised by Davies with the words that “reality is in the observation, not in the electron”. It follows that large accumulations of elementary particles, such as humans or observed phenomena on the macroscopic scale, only appear to have fundamental natures because of overwhelming statistical probabilities. In this view then 'objectivity' is a condition of statistics and not of essence or nature, and in this regard we can raise the question of whether statistical number and quantity are in fact properties of the alleged 'objective' world or of our symbolically-cognitive human minds. While this excursion of thoughts does not answer the initial question of what we are to do, it nonetheless highlights an interesting problem.

In our exposition of the Classical Image of the World-Beyond-Worlds, which might be termed a review of the fundamental concepts which structure human visionary experience, one philosopher, Immanuel Kant, was notable by his absence, largely because an exposition of one of his central themes, his interpretation of the Platonic noumenon, is more appropriately placed here, once the quantum world has broken down the Image and ushered in an era of perceptual indeterminacy.

Kant considered the sum of human knowledge as consisting of phenomena experienced by human senses, and assigned that which existed outside these phenomena to the noumenon (νουμενον, the mediopassive form of the Greek verb νοειν 'I think, I know', itself derived rather paradoxically from νους 'mind, perception'). This he defined as the unknowable reality behind and beyond what is presented to the human consciousness, or a hypothetical event or object that is known without the use of the senses. Like the ultimate in the Classical Image, whenever we utilise a concept or name to describe events in the noumenal, we are in truth describing sensual events of the phenomenal, and as such the noumenal is fundamentally unknowable. He further posited that any given object or event could be said to possess two aspects: the phenomenal experience of the object as understood by the senses and the noumenal 'thing-in-itself'.

At first, the boundary between the phenomenal and the noumenal appears to be rather rigid, but just as with our Classical Image, quantum mechanical views of these definitions of the noumenon and the 'thing-in-itself' raise questions which begin to blur the distinctions and, in my view, empty the concepts themselves of useful meaning.

We might begin with the notion of human sensual attenuation, a perceptual process in which the information which arrives at our sense organs is attenuated, filtered and modified through various neurological processes, including symbolic cognition, before arriving at consciousness. This process begs the question then of what constitutes the senses and thus what shall be considered noumenal: does only the filtered information presented to consciousness count as phenomenal, with the remainder, which has presumably been presented to the unconscious in one or a variety of forms, as noumenally unseen and thus unexperienced?

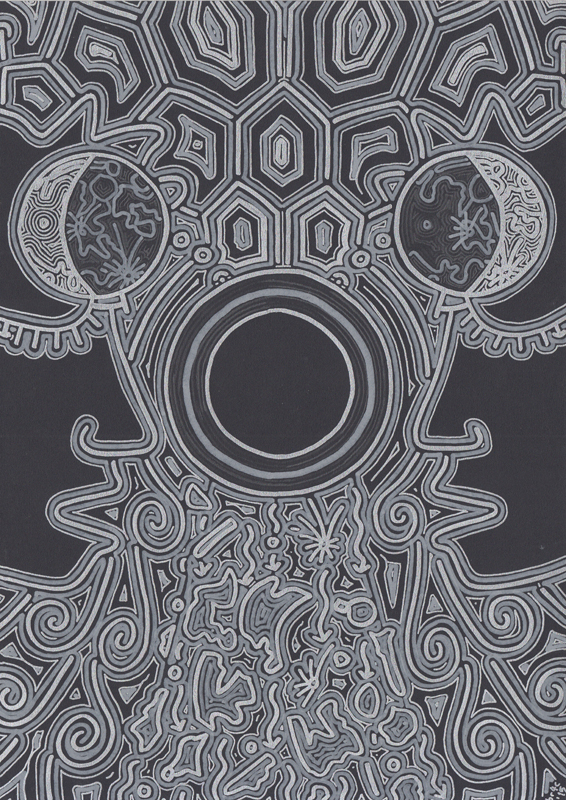

Once again we find that bivalent models are not really sufficient to maintain meaning when we begin to look at the observed situations rather than ideals, and gradations appear, liberating a kind of epinoumenal, which arises to take account of the information which is pseudo-experienced by the human unconscious. We might speculate for a brief moment that visionary experience and other altered states of consciousness can access this pseudo-sensual, epinoumenal internal realm and thus render it phenomenal and known.

The bivalent dynamic also breaks down in a consideration of human technological progress and the instruments used to make observations of the universe. For example, before the nineteenth century in which knowledge of the emission and modulation of radio waves became known, astronomical and other radio sources were nonetheless existent, but the invention of radio receivers allowed the interpretation of these sources into formats that were sensible to human perception. Once such sources become known, they obviously become phenomenal, but what of the situation where one knows that the radio source exists (having concluded this by observing the existence, for example, of a radio station whose premises are attended and showing as transmitting) but one currently does not have a radio receiver at hand to verify its existence? The radio waves that we know must be being emitted partake neither of the noumenal or phenomenal, but of this aforementioned epinoumenal.

We might thus tentatively suggest this epinoumenal as the process or the conceptual space in which the noumenal becomes phenomenal, through the neurological or technological processing of raw, unstructured experience into sensibility, but when we come to consider the whole Kantian model in light of what we know of quantum theory, it begins to seem as though this epinoumenal is merely propping up a situation that requires rejection rather than modification.

Kant's image of the 'thing-in-itself’, being the hypothetical aspect of an object or event that is exterior to our experience, and independent of any interaction or observation, is an impossibility in the quantum view: the 'thing' in question must of necessity partake of the same complementarity and indeterminacy that we find for elementary particles, and thus, its alleged 'objective' reality is not noumenal or unknowable but indeterminate and meaningless. The 'in-itselfness' is absent and as irrelevant for an accurate description of the 'thing' as it is for the elementary particle.

It is worth stating again for clarity that in the quantum view there is no essence, no determinism and no reality independent of the observation, and the 'world as it is' or 'thing-in-itself' becomes thus an imaginary concept which, we may speculate, represents a fundamental aspect of innate human perception and expectation, rather than of a universe bound by the strange realities of quantum systems. A dichotomy between noumenal and phenomenal is not useful here, whether modified with the epinoumenal or not: there is only phenomenon (or better still: observation) and indeterminacy. This distinction is not semantic, for quantum indeterminacy extinguishes all certainty as to the solid existence of an unobserved noumenon.

The Kantian model of the noumenal is thus rejected as an inappropriate image for the accurate expression of reality as we humans currently understand it, and a priori properties, precluded in quantum mechanics, must therefore be considered as being founded upon human perception and expectation, rather than the datum observable universe. This insistence on the application of quantum theory to objects and events in the human-scale world might seem at first like splitting hairs: an 'in-itselfness' is surely a good working assumption to make when observing or otherwise dealing with macroscopic 'things' but in the final analysis this remains a statistical condition rather than a fundamental expression.

Given that one of our principal themes is visionary perception, however, we must consider that human neurology is founded upon precisely the kind of quantum interactions that were explored in the preceding section. Whether a neurotransmitter should fire or not, and thus either liberate a cascade of similar events leading to a chain of neuron activations or not, has been posited to depend in part upon non-deterministic quantum phenomena, and the phenomenon of stochastic resonance, in which a group of neurons are able to detect patterns in high-noise environments, exhibit the same probability behaviours and statistical aggregates that we see for elementary particles. Thus in the realm of human perception, non-determinism and statistical aggregates within neurology make reality real, not external concepts of the noumenal or the essential. A strict focus on the primacy of quantum theory implications for reality and perception is preferential to macroscopic approximations therefore.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed