The 14th-century BC Song of Ullikummi is a well-preserved text found among the 30,000 clay tablets in the Cuneiform Royal Archive at Hattusa, the sometime capital of the Hittite Empire, near the modern town of Boğazköy, Çorum Province, Turkey. Detailing a battle between the gods which is occasionally reminiscent of later Greek texts such as Hesiod's Theogony and the myth of Typhon, Ullikummi recounts a somewhat surreal attempt by Kumarbi to overthrow the Storm God Teshub and destroy the city of Kummiya. Rather than being a Hittite story, however, its cast of characters reveals it to be a Hurrian myth from northern Syria, and this tale is one of a large corpus of mythology recorded in the Hittite language that discloses an extensive cultural exchange between the two civilisations.

on the son whom Fate and Mother Goddesses gave me?

Out of her body like a blade he sprang.

He shall go! Ullikummi shall be his name!

Up to Heaven to kingship he shall go,

and he shall press down upon Kummiya...

The Storm-God he shall strike,

and he will pound him like salt,

and he will crush him like an ant with his foot!

In one month a league he shall grow!

But the stone which is at his head,

his eyes will be covered...

his body of stone, of kunkunuzzi

And in the sea on his knees

like a blade he stood.

Out of the water he stood, the Stone,

of great height, and the sea

up to the place of the belt

like a garment reached

Up in Heaven the temples

and the chamber he reached...

The king of Kummiya set his face

upon the dreadful kunkunuzzi,

and from anger his heart became altered...

his tears like streams flowed forth.

In front of whom do you fill your mouth with song?

The man is deaf and hears not!

The man is blind and sees not!

And mercy he has not!

Tasmisu descends into the deepest realm of the Underworld, the Apsu, the source of all the world's water, where dwells Ea, god of wisdom and magic, in order to take advice that might save Teshub. Ea visits Upelluri to ask whether he has noticed the great stone giant standing on his shoulders. Upelluri's reply discloses his primordial nature:

upon me, I knew nothing.

When they came to cut apart Heaven and Earth

with an axe, I knew nothing.

Now, something makes my shoulder hurt,

but I know not who he is, this god!

Open again the Grandfatherly storehouse,

they shall bring out the ardala-axe

with which they cut apart Heaven and Earth!

And as for Ullikummi, the kunkunuzzi,

under his feet shall we cut,

whom Kumarbi raised as a rebel

against the gods!

What then can we make of this strange myth? As rebellious giants go, Ullikummi strikes us as particularly odd and passive in contrast to more famous – and more active – rebels from Greek or Babylonian mythology (or indeed from other episodes in Hittite and Hurrian myth). Blind, deaf and impervious to weapons other than the primordial ardala, Ullikummi neither speaks nor moves, but simply rises upwards as he grows to threaten Heaven with his very bulk, and otherwise seems to lack any kind of agency.

Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara

To understand something of the real-world referent that the Song of Ullikummi discloses, it is necessary to move away from archetypal, psychological and transcendent interpretations of myth to delve into an often-disregarded aspect: the recording of practical or noteworthy real-world information through the use of highly specific symbolism, something commonly termed the Technical Language of Myth. The world's myth systems are replete with references to astronomical phenomena, plant lore and former ritual practices, all of which in an archaic mind would have had immediate and self-evident pragmatic uses.

(In passing, I have explored the technical language of astronomical myth at length in my 2005 essay entitled The House Of The Sky and intend to research other technical aspects in forthcoming posts here, one of which, to be titled Technical Languages in Myth will outline this stimulating aspect of mythology in more detail.)

But there are times when major cataclysmic events also seem to be recorded in this same technical language, and Ullikummi appears to be just such a story, possibly even an eye-witness account. In being so, the Song also discloses something of an archaic perceptual worldview, since, as Barber & Barber point out:

“Humans will things to happen, then set about to make them happen. Therefore if something happens, it must have been willed.”

Thus, impersonal real-world events become conceived as having been caused by the will of gods, in this case Kumarbi. Hence, the beginning of the story – Kumarbi's desire to destroy Teshub – can be understood as little more than a rationalisation of some inexplicable natural phenomenon, embodied in Ullikummi, that threatened the existence of the Hittite-Hurrian world and shook it to its foundations. Other events, such as the conversation with Upelluri and Teshub's emotional collapse also belong to this post-hoc explanatory sphere.

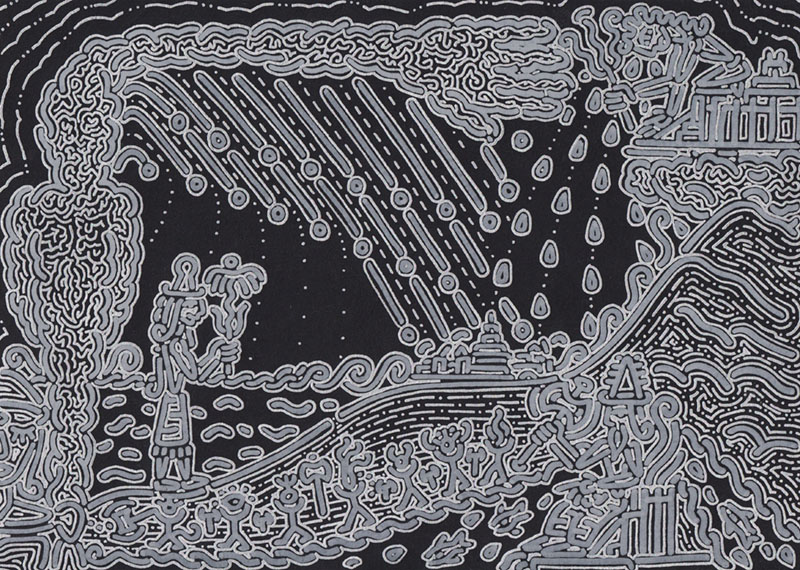

Barber & Barber argue that the manifestation of technical languages within myth can be clarified when one “adjusts the camera angle”, that is to say, to uncover the referent of a given story by looking solely at the images – without their attendant rationalisations – within it and matching them up to known but remarkable real-world phenomena. In the present tale, there are five striking images of note:

- The rapid and startling emergence of a great stone giant from the sea in the far west

- The giant is blind, deaf, merciless and without agency, and is described as a stone blade standing vertically in the waters and cutting the sky

- The accompaniment of that emergence with thunder, lightning and other loud sounds

- The shaking of Heaven and the destruction of at least one earthly city, Kummiya

- The final defeat of the giant by cutting under his feet to sever him from the Fundament

The event destroyed the Cycladic civilisation on Santorini and other islands, and severely affected the Minoan and emerging Mycenaean civilisations on Crete and the Greek mainland, with ash-fall from the volcano being detected as far away as Syria, eastern Turkey and Egypt. The eruption itself was likely to have been seen and heard from similarly distant locales, and it is worth noting that the location of the eruption in the far west of the known world of the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean chimes well with the story's origin in Syria. Barber & Barber hold that the Song of Ullikummi records this event in vivid detail, and I consider the imagery to be accurate enough as to perhaps constitute an eyewitness account, albeit one told with an archaic voice, where impersonal natural forces are willed and personified.

If this is difficult to reconcile, it is necessary to understand how this event would have been experienced as far away as Syria, where the Hurrians lived, or central Turkey, the region of the Hittites. Let us consider for a moment, a geological report of the Mount St Helens eruption in 1980 made from Portland, Oregon, some 200 miles to the southwest of the volcano:

“In the air, boiling into the sky to an altitude of 65,000-80,000 feet... the volcano's vertical plume of gas, ash, steam and dust trailed off...Inside that tall plume could be seen strong convective upwelling currents, while stratus clouds were entrained... at several levels within the vertical column. At the same time, violent flashes of lightning were seen throughout the height of the column, and as the mushroom cap formed, it began expanding outward at an altitude of about 50,000 feet...”

Here, then, is a powerful image of a column of volcanic ash, visually indistinguishable from stone, rising rapidly and standing vertically in the sky, accompanied by thunder and lightning and with a large bulbous mushroom-like head at its apex. Imagined with an archaic mindset, it is difficult to see how the volcanic column could not be seen as a terrifying giant striking the sky – indeed a photograph of the 2010 eruption of Mt Sinabung in Indonesia seems to capture the very face of such a volcanic giant!

The sight of a great column of ash and lightning standing in the sea and reaching to Heaven, disrupting weather systems and 'shaking the sky', must have seemed unappeasable to the Hurrians and Hittites, and the ash-fall and deposition of pumice and basalt fragments on the land during and after the eruption would have seemed to have confirmed that this 'giant' was indeed made of stone. Teshub's initial reaction seems to disclose a memory of the panic that many must have felt, perhaps moving to higher ground for safety or to better understand what was happening.

The destruction of the city of Kummiya (a city whose location is currently unknown) may have been wrought by the tsunami that is held to have ravaged the eastern Mediterranean after the eruption chamber at Thera collapsed in on itself. It is also possible that the word kunkunuzzi, often translated as a magical type of rock, could refer to pumice, which has the curious property of floating on water, or perhaps shocked volcanic quartz.

But it is the final image, of the cutting of the stone giant's feet, which bears the most authentic stamp of eye-witness information. Barber & Barber explain why: “Eventually... the ash-pillar that seems rooted to the earth separates from the bottom, once no more [volcanic] ejecta are being fed into it, and then it slowly disperses.” The column begins to drift upwards, having lost contact with the earth, or in this case, the surface of the sea, resonating with the removal of Ullikummi from his feet upwards and causing his defeat.

Here, then, we can see something of the process of myth-making in action through the lens of the archaic mind which projects animism onto every phenomenon, including inexplicable and cataclysmic events, and it is worth reminding ourselves that the Song of Ullikummi was recorded within two centuries of the Theran eruption. Later and more developed myths among the Greeks and Egyptians which contained similar technical references to the collective memories of this event were more developed and idealised, with 'rebels' and giants of greater agency and strength. Burkert gives many details of survivals of Bronze Age Mesopotamian and Hittite mythforms in Greek religion.

One such descendant of Ullikummi must surely be the myth of Atlantis, which when viewed with a technical camera angle overwhelmingly points to a Theran/Aegean provenance. Literalist readers of the Platonic account may disagree (although Campbell's perennial admonition, that such literal readings kill the spirit of myth, bears relevance here!) and I intend to explore this aspect more deeply another time. For now, it is interesting to note how strongly the primordial figure of Upelluri seems to resonate with the much later (and much more idealised) Greek figure of Atlas, and to consider the etymological similarity of the Pre-Greek names Atlas and Atlantis as pointing a road open for future consideration.

Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul T. Barber, When They Severed Earth From Sky: How the Human Mind Shapes Myth, Princeton University Press, 2004

O. R. Gurney, The Hittites, Penguin Paperback, 1990

Hans Gustav Guterbock, The Song of Ullikummi: Revised Text of the Hittite version of a Hurrian Myth, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Vol. 5 No.4, 1951, urls: http://limudbchevruta.wiki.huji.ac.il/images/Ullikummi_1.pdf and http://limudbchevruta.wiki.huji.ac.il/images/Ullikummi_2.pdf , retrieved September 2013

Bruce Rimell, The House of The Sky - A History & Future Of Mythical Floods, 2005, url: http://www.biroz.net/words/house-of-sky.htm , retrieved January 2010

Charles Rosenfeld and Robert Cooke, Earthfire, MIT Press, 1982

George E. Vougiokalakis, Alexandra Doumas (trans.), The Minoan Eruption of the Thera Volcano and the Aegean World, Society for the Promotion of Studies on Prehistoric Thera, 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed